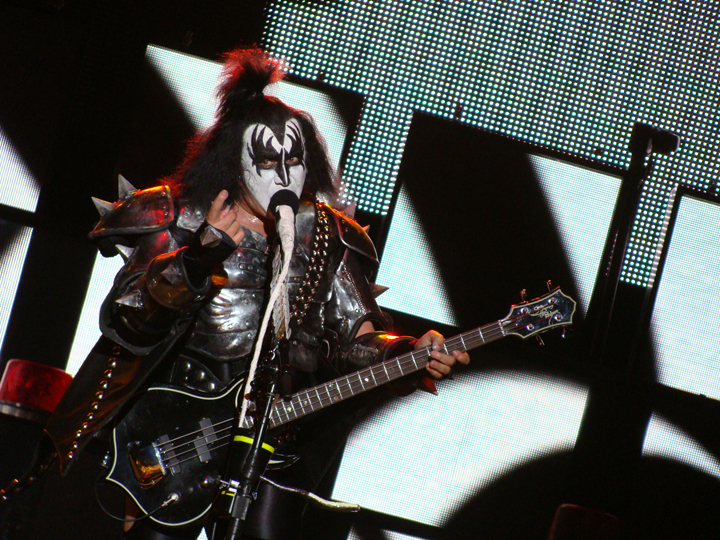

In December 2001, on a visit home to the United States, and having been deprived of easy access to American radio for over a year while living in Israel, I took advantage of the break from my research on Hebrew and Israeli culture to catch up on all things American. I tuned in to a local New York satellite of National Public Radio to find no less a popular cultural icon than the former lead singer of KISS correcting the interviewer's Hebrew:

Gene Simmons: Oh, thank you so much [for the introduction] and since this is National Public Radio and it prides itself on accurate information—most of it sounded good—I stand guilty as charged and proud to say that I'm a mama's boy. However, point one is you mispronounced my Hebrew name. It's not Ḥayim, which is the sort of sniveling please-don't-beat-me-up Ashkenazi European way . . .

Leonard Lopate: Which is what I grew up in . . .

Gene Simmons: Which is—hey, that's why you get beaten up. I don't. The sefaradit way is the correct way. It's Ḥayim, emphasis on the second vowel, like the Israelis do.

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda was a major figure in the language revival movement, and one of the early Ashkenazic promoters of the "sefaradit way." To further his revivalist goals, he taught Hebrew in Jewish schools in Palestine and supported the inculcation of a so-called Sephardic accent. His magnum opus was a comprehensive Hebrew dictionary, and he is known for having fashioned new words out of ancient roots to name phenomena of modern life, and for his practice of sending his young son outside to declaim these neologisms and their definitions. It is hard to imagine a less likely heir to Ben-Yehuda, mythical "Father of Modern Hebrew," than the lead singer of KISS. Yet Simmons spends the opening moments of his interview rehearsing what are by now clichés of Modern Hebrew—a diatribe that reached more listeners in a few moments than a year's worth of Ben-Yehuda's public pronouncements of new words or public statements in favor of the Sephardic stress system. Simmons, a.k.a. Chaim Witz, waged one of the longest-lasting teenage rebellions in American history, and made a career of rejecting the attitudes his short-lived education in a Brooklyn yeshiva would have tried to instill in him. The rejection of what Leonard Lopate "grew up in" jibes with an Israeli sense of a new Jewishness, one with which Simmons seems to identify. In matters of Hebrew diction Simmons would have made Ben-Yehuda proud, for his passion if not his expertise.

As it happens, Lopate did pronounce Simmons's name as an Israeli would. In Hebrew, the word ḥayim means "life," and when used as a common noun is pronounced with the stress on the final syllable. Names, however, are an exception to the rule—even the Israelis do not say them "like the Israelis do." They invariably pronounce the name with the stress on the penultimate syllable, in this case the first, as Ḥayim, what he calls the "please-don't-beat-me-up Ashkenazi European way." (For Israelis, this pronunciation is a gesture of intimacy associated with Yiddish and the memory of Jewish eastern Europe; the penultimate stress is sometimes used even for names usually pronounced with a terminal stress.)

As with all hypercorrections, Simmons's objection to Ḥayim is a sign of the status and associations of a particular mode of speech. Simmons was born in Haifa a year after the founding of the State of Israel. He immigrated with his mother to the United States when he was eight years old. Despite his ignorance of "the way Israelis do" and do not pronounce his name, he is in tune with a cultural phenomenon that preceded the founding of the state and was continually reinforced with the institutionalization of Hebrew as the official language of the Jewish settlement in Palestine and of the State of Israel. The accent system he invokes is indeed associated with a masculine, nationalist Jewish persona—especially when contrasted with what from an Israeli perspective is an outdated Hebrew.

A commonplace among Americans who take an interest in Hebrew culture is that poetry occupies a more central place in the Israeli consciousness than in our own culture. This alone, however, does not account for the number of times that, after hearing the subject of my research, my Israeli interlocutors responded in verse. To be precise, they quoted an early poem by the national poet Ḥayim Naḥman Bialik, "To the Bird":

Sholom rov shuvekh, ẓiporoh neḥmedes, me-'arẓos ha-ḥom 'el ḥaloni—

'el kolekh ki 'orev mah nafshi kholosoh, ba-ḥoref bi-'ozvekh me'oni.

Welcome upon your return, lovely bird, From the hot lands to my window—

How my soul has yearned for your voice so sweet, In the winter when you leave my dwelling.

In short, they responded with the only work whose Askenazic Hebrew is consistently preserved in the literature curriculum of Israeli schools. By mentioning the transition to new-accent Hebrew I made speakers recall an artifact of an older Modern Hebrew—one of a very few reminders that Hebrew speech in the Land of Israel in modern times was ever ruled by different protocols for pronunciation than it is today. To be more precise, my Israeli interlocutors offered a partial rendering of an Ashkenazic Hebrew. Not inappropriately for accentual-syllabic poetry, they preserved the rhythm of the penultimate stress—if also somewhat imperfectly as the speaker's habitual dialect fought this overriding of the rules of Israeli Hebrew (Neḥama maintains a penultimate stress pattern consistently—while vowels and consonants conform to standard Israeli.)

A compromised rendering of Ashkenazic Hebrew can also be heard in the recitation of a poem far more well known the world over than anything Bialik ever wrote, composed by a poet far less celebrated. With each performance of the national anthem—"Ha-tikvah" (The hope), based on Naftali Herz Imber's "Our Hope"—Israelis utilize an Ashkenazic, penultimate stress system with an admixture of terminal stress at the ends of lines. The State of Israel's official anthem is distinct among national anthems: it was neither composed nor is it recited in the standard national language.

Whether sung by Al Jolson, Barbara Streisand, the Israeli pop singer of Moroccan-Jewish descent, Maya Bouskilla, or Rita, a singer of Iranian-Jewish heritage, "Ha-tikvah" preserves an older nationalist aspiration. Precisely by entertaining both the Ashkenazic past and, in its consonants, the Israeli present, the sounds of "Ha-tikvah" echo a romantic story of Ashkenazic nationalist longing inscribed in the anthem's lyrics:

U-l-fa'atei mizraḥ kadimah

'ayin le-ẓiyon ẓofiyah

And onwards, to the eastern corners

An eye looks towards Zion (lines 3–4)

Many have understandably criticized its exclusion of Arabs. The story and sounds of "Ha-tikvah," however, also exclude the Jews of the Middle East who would have turned west to face Zion—and pronounced the hope ha-tikvah, not ha-tikvah.

Although Ashkenazic is more commonly heard among American Jews of Ashkenazic descent than among Israelis, communities identifying as "liberal" or "Zionist" or "Modern Orthodox" most often adopt an Israeli accent as an expression of their religious-ethnic-political identity, peppered with American intonations. When Imber composed "Our Hope" in 1878, and Bialik composed "To the Bird" in 1891, however, the traditional Ashkenazic dialects were still predominant among Ashkenazic Jews in Europe and Palestine and the United States. Ben-Yehuda's and others' attempts to adopt and teach a Sephardicized Hebrew in Palestine were just beginning.

Thanks to Bialik's and Shaul Tchernichovsky's prosodic innovations, by the end of the twentieth century there were Hebrew poems with the accentual-syllabic sounds of European poetry (English, German, Russian, Yiddish) in which the regular recurrence of stressed syllables generates rhythm. Unfortunately for Bialik, the stress system in which he spoke and wrote was not the one that would become the standard for spoken Hebrew. In 1892, Bialik's poetic persona could sing to the bird melodiously in an Ashkenazic Hebrew from the pages of The Orchard. By 1894 Bialik regretted the "distorted" Hebrew in which he would nevertheless continue to compose. He expressed this sentiment again thirteen years later while in Palestine. He had heard the future of Hebrew and it was not his. When children read his poetry, they might even wonder at Bialik's reputation: where was the beauty, the rhythm? It is perhaps this additional context that makes sense of his poem's current position as the paradigm of Ashkenazic poetic Hebrew. The bird comes from Palestine and the poet questions her throughout, asking after the inhabitants of Zion, and she never says a word.

But what would the bird sound like if she did respond to the speaker's questions?

In the retrospect of Bialik's visit to Palestine in 1907, and his realization that his own Hebrew pronunciation might be extinct within a few years, one is tempted to chide the poet: if only he had let her have her say, he might have learned a thing or two about the new pronunciation. Even as Bialik's Hebrew was replaced by a pseudo-Sephardic dialect, his poetry retained pride of place in the national poetic canon. The bird-muse had in the meantime opened her mouth, becoming the new citizen of the Hebrew-speaking nation, subjected to the babble of a hopelessly exilic Jew. What upon publication expressed the nationalism of Jews of Russia and eastern Europe, of their longing for the land of their forefathers, now marks the difference of the Diaspora even more, offering an impression of the exilic Jew from the bird's-eye view of the nation. The bird visits the speaker on her annual migration from Palestine and stays for the duration of the poem, just long enough to spur a new cycle of longing for the bird's return and for the Land of Israel itself. Her silence represents the poet's distance from the homeland and his unfulfilled nationalist desire; it memorializes the desire for a Zion that is always just out of reach. The national anthem's sound likewise puts Israel's citizens in Bialik's proverbial shoes, marking the distance from—and thereby the longing for—the homeland.