Linguistic patterns deviate (in baroque and romantic poets more, in classicist poets less) from the regular versification pattern, but at certain crucial points they have coinciding downbeats. When regularity is suspended in the linguistic dimension, the regular alternation in the versification pattern may reverberate for a very short time in short-term memory. A rhythmical performance is one that accommodates the conflicting linguistic and versification patterns such that both can be perceived simultaneously. To enable this, mental processing space must be saved by grouping and clear-cut articulation of phonemes, word endings, phrase endings, and line endings.

I don’t intend to present in this article all the metrical theories that tried, in the course of the twentieth century, to solve the riddle of poetic rhythm. I only want to briefly confront the approach advocated here with an approach that lately became fashionable again, that of equal or proportional timing. The question is, what is it that recurs with some regularity? According to the equal-timers’ approach, it is some immediately observable, measurable time periods that recur. According to the structuralist-cognitive approach proposed here, it is an abstract pattern of weak and strong positions, not immediately observable, that alternate regularly. As to the assumption of recurring equal or proportional time periods, it has been time and again refuted by electronic equipment since the early twentieth century. Despite accumulating evidence to the contrary, belief in equal timing persists. The purpose of this article is to produce evidence to support the structuralist-cognitive approach.

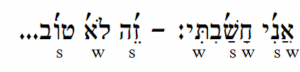

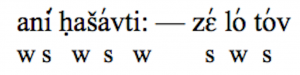

Let us consider at some length the following verse line by Nathan Alterman:

"I thought: — This [is] not good"

Listen:

Above the Hebrew original and the phonetic transcription small strokes mark linguistically stressed syllables. Under the text, the regularly alternating /w/ and /s/ letters mark weak and strong positions of the versification pattern. The two patterns were assigned independently of each other. Thus, they show up where the stressed and unstressed syllables coincide with strong and weak positions, respectively, and where they deviate. In English and Hebrew linguistic prosody, when three consecutive equally stressed syllables occur, there is license to demote the middle stress in order to gain regularity. In reading poetry, however, the majority of leading British actors don’t take advantage of this license to secure regular rhythm in, for instance, the iambic meter. Instead, they have recourse to grouping and overarticulation to save mental processing space, so as to make it possible to perceive concurrently the vocalized linguistic pattern and the suppressed versification pattern merely reverberating in short-term memory. Thus we can see how one actor, with one voice, can convey three concurring patterns: he vocalizes the linguistic pattern; in his performance he has recourse to grouping and overarticulation, so as to save mental processing space, enabling the perception of the versification pattern merely reverberating in short-term memory. I strongly suspect that Yossi Banay overarticulates the words “zɛ lo tov” not for rhythmical but rhetorical purposes. This, however, does not detract from the rhythmic effect of these vocal manipulations.

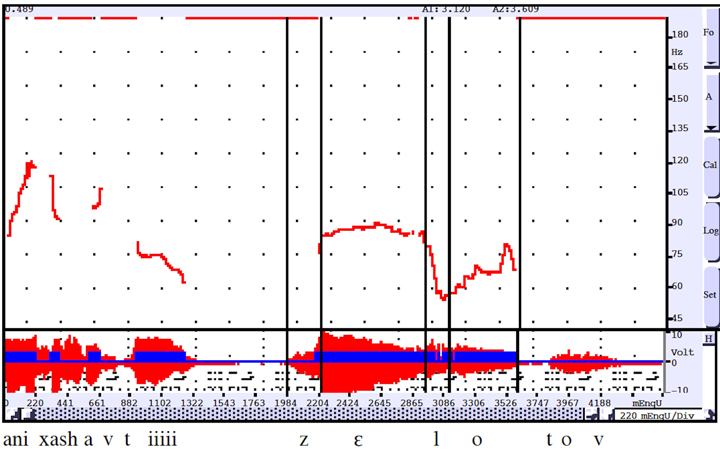

As I marked the meter of this verse line on the paper, it is the iambic tetrameter. Every even metrical position is stressed, every odd position unstressed, and there are eight positions all in all. On this level, then, there is regular periodicity. As performed by Yossi Banay, the seventh (weak) position, however, is occupied by a stressed syllable. Three features are conspicuous in this performance. The three words “zɛ lo tov” are equally stressed, they are perceived as one phrase, but are perceived as sharply separated from one another: their boundaries appear to be overarticulated by longish pauses. For the equal timers this is evidence that there is regular alteration between overstressed linguistic stuff and periods of silence, reinforcing the iambic (but not the tetrameter) pattern. When, however, we have a look at the output of the speech processor, we have a small surprise in store.

The word “tov” is separated from “lo” by a considerable pause. However, between “zɛ” and “lo” there is no measurable pause. The sense of discontinuity is generated by a long-falling intonation contour on l. It would appear, then, that in indicating discontinuity there is a trade-off between two acoustic cues: a pause and a long-falling intonation contour. The fact that this intonation contour is on l and not before it suggests that, in spite of all, the two words are tightly grouped together.

It is widely accepted today that the human cognitive system has limited channel capacity, which cannot be extended by training, only by recoding the processed stuff in a more parsimonious way. Grouping and discontinuity (overarticulation) are such recoding devices. They save mental processing space needed for hearing the vocalized linguistic stuff, and perceive, at the same time, the acoustically suspended versification pattern reverberating for a short time in short-term memory (what Chatman calls “metrical set”).

The foregoing example suggests, then, that what is important here is the articulating (discontinuity) effect of the two acoustic cues rather than the possibility of equal or proportional timing, which would apply to only one of them, if at all. What is more, a pause before a stop midword is perceived as the overarticulation of the stop rather than a period of silence; here, since it occurs in mid-phrase, between two monosyllables, it is perceived as a period of silence as well.

I believe that equal or proportional time periods are, at best, properties of casual performances, for which it is difficult to find an example. I, at least, haven't yet encountered one.