Transgressions by geographically diverse contemporary Jewish artists go far beyond an imagined broken commandment. Jewish artists paint canvases where biblical figures talk about fucking within comic book speech balloons (Archie Rand, 1992) and reconfigure film footage of Hitler to make it appear as if he is apologizing, in Hebrew, for the Final Solution (Boaz Arad, 2000). In other words, the sacred text and the sacred memory—the Bible and the Holocaust—are startlingly desacralized.

Even before the sacred became desacralized, the simple presence of Jewishness in art made some viewers uncomfortable. That is, for some it felt unseemly, transgressively indecorous, to have Jewish subject matter appear in art. In a 1955 review in Commentary magazine, for instance, critic Hilton Kramer denigrated Hyman Bloom's expressionist canvases of rabbis and other Jewish subjects: "To the 'foreign' eye, which brings no associations to it, it must be as absorbing as a kosher dinner—a matter of taste. But for the observer who has associations with this imagery from childhood onwards, Bloom's Jewish paintings stimulate the same surprise and dismay one feels at finding gefilte fish at a cocktail party. It's a bit too stylish to be palatable."

Curator Norman Kleeblatt of New York's Jewish Museum experienced similar discomfort when confronted by especially strong Jewish material, but he dealt with that reaction more productively. Kleeblatt visited Archie Rand's studio in 1989, where he saw the artist's Fifty-Four Chapter Paintings. This series of like-numbered canvases depicts the weekly chapters of the Torah sometimes with literal iconography and at other times symbolically or abstractly, all labeled in Hebrew. Reacting with "embarrassment," to use Kleeblatt's words, at the paintings' "excessive 'Jewishness,'" the curator soon resolved to explore the upsurge in Jewish material in several artists' work. Rand's Fifty-Four Chapter Paintings inspired Kleeblatt's groundbreaking exhibition, Too Jewish?: Challenging Traditional Identities (1996).

Rand's vast body of work, transgressive in style and subject, is inspired by the artist's belief that he must augment Jewish pictorial expression, which brings us full circle to the misunderstood prohibition against graven images: "I realized that one of the rights and obligations of any culture is to manifest a visual exponent of that culture. Judaism had been forced externally and internally to ignore that impulse." Let us now look at some paintings from Rand's breakthrough series, Sixty Paintings from the Bible (1992), his earliest on a Jewish theme in a comic book style and largest series to that moment, to better understand his relentlessly consistent interest in creating avant-garde art with Jewish subject matter.

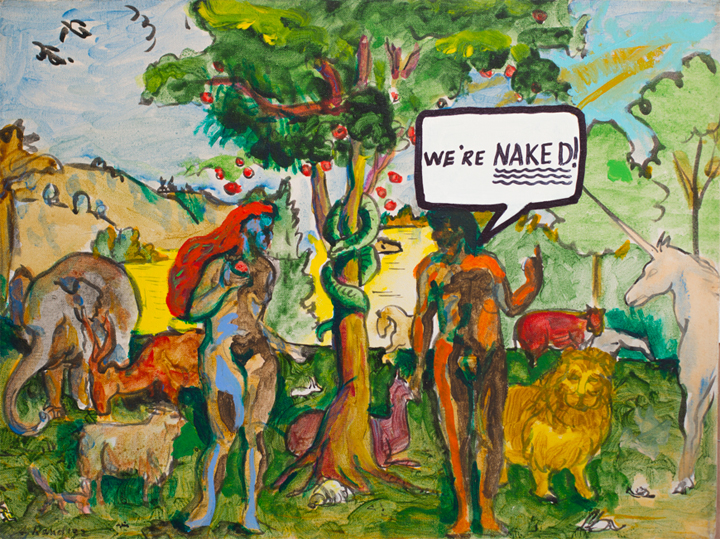

Each loosely painted canvas in Sixty Paintings from the Bible portrays a familiar moment from the Hebrew Bible or the Apocrypha, most rendered expressionistically and in comic book Technicolor. Speech bubbles, encapsulating text written in marker, explicate each story. Within the various-sized balloons Rand inserts everyday vernacular, shaped by closely consulting corresponding biblical passages. Looking at the Standard English translations and then examining the Hebrew, Rand concluded that the English often did not quite accord. Recognizing that the original words were more powerful and dramatic, Rand introduced his loose adaptations of the biblical text. He likens this process to one used by Borscht Belt performers: take an expected conclusion and throw a curve ball. Rand's colloquial interpretations, both stylistically and through the attribution of common language to the biblical figures, convey drama and sometimes humor, adding a fresh, accessible, postmodern perspective to foundational stories that have shaped Judaism as well as human civilization. The canvases in the series offer unexpected rereadings designed to make viewers think twice about proverbial tales.

Adam, the first canvas in the series, reveals Adam and Eve's nudity more obviously and wittily than the old masters (fig. 1). Jan van Eyck, for example, had the original humans press fig leaves against their genitals in The Ghent Altarpiece (1430–1432). The fig leaf coverings indicate the couple's newfound shame—and minimize the embarrassment of fifteenth-century churchgoers. Masaccio painted the figures in Adam and Eve Fleeing the Garden of Eden in the Brancacci Chapel's Expulsion fresco (1425) nude, but a later artist covered the pair's genitalia (1620). In contrast, Rand cuts right to the chase, demarcating the pairs' exposed sex organs with green triangular outlines. Separated from a red-haired, Rubenesque Eve standing beside the Tree of Life at the center of the composition, Adam turns to his mate and shouts, "We're naked!" An exclamation point, large, capitalized lettering, and triple underlining convey his surprise.

Unafraid to be subversive, especially in the realm of sexuality, Rand makes evident the seamier moments in the Bible. An unnamed woman of Egyptian descent, known only as Potiphar's wife, attempts to seduce Joseph. The biblical text dances around any lascivious aspects, but Rand's canvas puts them front and center (fig. 3). Lounging nude in an elaborate canopied bed with a sheet barely—and provocatively—wrapped around her body, Potiphar's wife grabs the fleeing Joseph's flaming red cape, attempting to pull him back to her. She vulgarly exhorts, in large capital letters, "Fuck me!," as opposed to the mild language of the biblical passage (in its common English translation): "Lie with me!" (Genesis 39:12). Rand paints the interior of Potiphar's wife's bedroom, a place of sexuality and lust, in sensuous colors, whereas the outer, safer, public spaces of the palace appear only in gray.

Rand knew that by working on biblical subjects in the late twentieth century, even though the paintings are not meant to be theological in nature, he would probably be excluded from the modernist discourse (and he was). Namely, the canvases are considered transgressive by the mainstream art establishment because the subject matter is understood as passé. Nonetheless, Rand's ambitious, game-changing Sixty Paintings from the Bible was a risk with consequences he was willing to take, a risk which to this day resonates in his art.