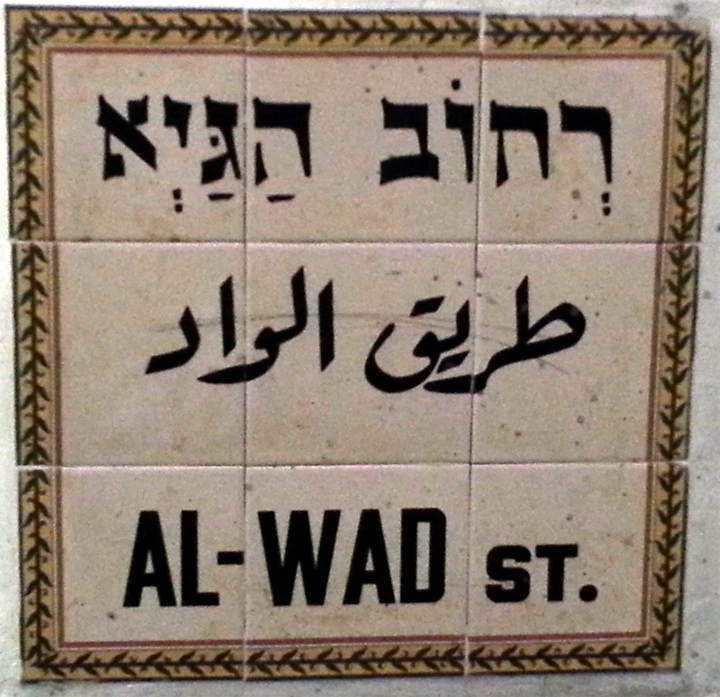

In my own work I've spent a good deal of time thinking about transgression in relation to a certain politics: the language politics of Hebrew and Arabic. In Israel/Palestine, the interweaving of the theological, the legal, and the spatial shapes every dimension of life, from the separation wall, checkpoints, and bypass roads, to separate school systems for Arabs and Jews and largely segregated residential patterns. In Hebrew, 'averah (transgression or trespass) is a near homonym of 'avirah (passing or crossing); both derive from the root '-v-r, which is also the source of 'ivri (Hebrew), those people from "beyond" the Euphrates River. In 1979, a young Palestinian Israeli writer, Anton Shammas, later the internationally renowned author of Arabesques, titled his second poetry collection Shetah hefker, "No-man's-land." The volume closes pensively: "I do not know / a language beyond this / and a language beyond this. / And I hallucinate in the no-man's-land." From his vantage point in the middle of this no-man's-land, the hallucinating poet looks out at one language then the other, seeking a "language beyond this" (safah me-'ever mi-zeh): a language beyond the virulent politics of separation. In the early 1980s, not long after the publication of his poem, Shammas had said of his Hebrew literary activity, "This whole thing is a kind of cultural trespassing, and the day may come when I will be punished for it."

I took this as the organizing metaphor for my 2014 book Poetic Trespass, which explored the relationship between Hebrew and Arabic in the cultural life of Israel/Palestine. There, I devoted a full chapter to the Hebrew poetry of Palestinians in Israel. Given the profound associations of Hebrew with Judaism as well as the storied role of Hebrew in political Zionism, it is hard to see how, for a Palestinian Arab, writing in Hebrew could be anything other than a politically fraught and psychologically double-edged act. Previously, literary critics had credited Palestinian writing in Hebrew with divesting the language of its Jewishness and recoding it as Israeli rather than Jewish. I didn't find this claim supported, however, by the Hebrew-language poetry of Palestinian writers, which draws deeply from the allusive wellspring of Jewish liturgy and heritage. My own reading of their verse probed how Palestinian poets contend directly with the Jewishness of Hebrew, appropriating it as a mode of self-expression and adapting it, often with considerable irony, to give voice to their own unique predicament.

Is their claim to Hebrew transgressive? From Jewish perspectives, the answer splits two ways. For ethnocentric nationalists who objectify Hebrew as the exclusive cultural property of Jews and the privileged signifier of Jewishness, the answer is yes; for liberals who view language as a labile and inherently porous medium that cannot be owned, the answer is an obvious no. But from a Palestinian perspective, is the choice of Hebrew as the medium of selfexpression a defiant intrusion onto Jewish territory and a disruption of Zionist norms, or a betrayal of Palestinian selfhood?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, their Hebrew verse is suffused with varieties of borders and with a persistent sense of transgression. Borders signify the split self, while transgression plays the chords of agonizing self-scrutiny, often sounded in a Jewish key. In a 1986 poem titled "'Al het" (For the sin), Na'im 'Araidi writes, "For the sin I committed against myself and my beloved / on the way to Jerusalem approaching Bethel / From the desert I took the fullness of my love / until Abraham laughed and Ishmael cried." The poem is modeled on the long Vidui (confession of sins) in the Yom Kippur liturgy, when worshipers collectively seek forgiveness of God; echoing this liturgy, subsequent stanzas of 'Araidi's poem repeat the refrain 'al het she-hatati, "for the sin I committed." In Anton Shammas's 1974 poem "I Feel the Crease," the speaker describes dropping tefillin from a roof while choking, of "making Kiddush / over the white city," and then compares the split in his soul to a crease running through Jesus's body in a worn-out print of the Last Supper.

Yet for all the fascination with transgression that I poured into the pages of my book, it turns out that such soulful ruminations on writing in Hebrew are virtually absent from the work of the Palestinian novelist, journalist, and screenwriter Sayed Kashua. If in Arabesques (1986), Shammas had referred to Hebrew as the "language of Grace," in Kashua's 2016 Native, a selection of his humorous vignettes for Haaretz, Hebrew is the language of bureaucratic dysfunction, of his children's swimming lessons, of the walk-in clinic in Jerusalem. In Native, transgression is mostly about staying too late at the bar and having a bit too much to drink. Arabic, by contrast, is the family language that, heartbreakingly, when voiced in public spurs a little Jewish boy to say "Eww, yuck" to the author's own small son.

This is not to say that Kashua's work is devoid of split selves or of self-doubt—to the contrary, he takes these themes and literary devices to new levels. In his 2010 Guf sheni yehid [Second Person Singular], for example, transgression is thematized through outright identity theft: a metaphor, perhaps, for self-betrayal. But on many levels from the thematic to the stylistic, Kashua demystified Palestinian writing in Hebrew, stripping it of its theological baggage. In fact, in Native, the only pushback he receives for writing in Hebrew comes during his book tour in the United States, from a Palestinian woman who calls it "the language in which your people are oppressed."

Reading Kashua has made me circle back on my earlier ideas and wonder if his matter-of-fact approach to Hebrew, which cuts through the mystique surrounding Palestinian Hebrew authorship, is not somehow the more transgressive attitude. Kashua seems to be saying: just own it. Granted, you can't own the language, but you can own the act of writing in it. Native's title says as much—in Hebrew, it's Ben ha-'arez, literally "son of the land" or "native son," but also an obvious pun on Kashua's public role as a columnist for Haaretz. Yet what many Hebrew speakers might miss is that ben ha-'arez is in fact a literal translation of the Arabic idiom ibn al-balad. This kind of trilingual punning in which languages flow into each other like tributaries with no clear point of origin exemplifies the creative potential of transgression. Will there ever be "a language beyond this" in Israel/Palestine, a fruitful commingling of the two languages? Hard to say, but in his books Kashua seems to have definitively moved the Palestinian Hebrew writer out of the Hebrew-Arabic no-man's-land.