This debate is not new. Jewish engagement with Muslimness in France has a long and complicated history. With this phrase, I mean Jewish depictions of what it meant to be Muslim and, more precisely, Jews' own relationship, or lack thereof, with Islam or Muslim identity. The Jewish engagement with Muslimness in France has historically oscillated largely between two poles. The first pole treats Muslimness as an element of shared culture with Jews, particularly those from North Africa or the Middle East. The second regards Muslimness as a useful foil that helps to legitimize Jewishness as more fully Western, European, assimilable, and French. Yet a third component of engagement, overlapping with the first two, has repeatedly emerged at times of crisis: one that uses the close affinities between North African Jews and Muslims as a survival strategy.

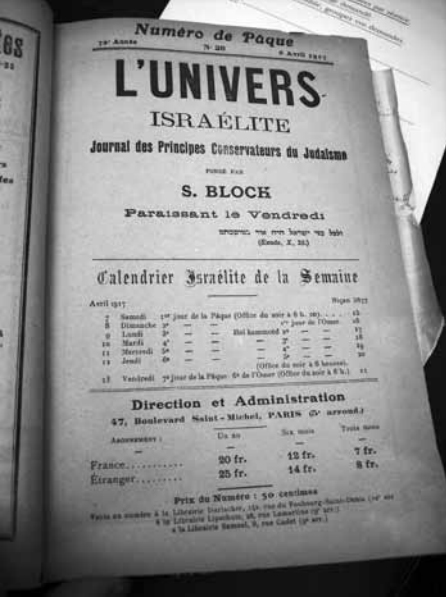

It was during World War I when, for the first time, Jews and Muslims began to interact in large numbers in metropolitan France. In April 1917, the popular weekly of traditional French Judaism, L'Univers Israélite, printed an article that recounted a conversation between two French soldiers in the trenches, one of them Jewish, the other Muslim. With Passover approaching, the Jewish soldier, named Habib, spoke to his Muslim comrade, Rahmoun, of the importance of human action in the Exodus story. He said that while he found Islam to be in "perfect harmony" with Judaism in most respects, he disagreed with the way the former "exalts the feeling of . . . submission to divine will, to the detriment of the human energy that is called upon to react constantly against evil."

In response, Rahmoun deemed his own faith the "daughter" of Judaism, and asserted that while Habib might question some Muslims' temperament, he should not misjudge the teachings of Islam. Rahmoun recounted a story from Muslim scripture in which Moses becomes ill while the Israelites are in the desert. For too long, Moses refuses to call a doctor, claiming his fate lies in God's hands. Finally, God calls out to Moses and explains that science is a divinely created art, and that Moses should accept a doctor's care. Having concluded his story, Rahmoun turned to his comrade and exclaimed, "You see, our religions profess the same doctrine. Faith should not prevent action; rather it should inspire and support it."

It is difficult to know if this exchange actually took place as reported. Yet both as a possible daily interaction and as a representation, the account illuminates crucial aspects of early Jewish-Muslim relations in France. Here we already see the push and pull of Jewish engagements with Muslimness on French soil. With pride and respect, Habib and Rahmoun noted each other's common membership in Abrahamic, monotheistic faiths that had overlapping beliefs and textual traditions.

Like most Jews and Muslims who fought together in the French lines, both soldiers appear to have hailed from North Africa. Thus their mutual knowledge was part of a shared Mediterranean cultural and even religious heritage that they brought with them to the métropole. At the same time, the soldiers' shared loyalty to France was implicitly overriding. The Jewish soldier appeared as a conduit within the army's role as the "school of the fatherland." The Jew from Algeria, a French citizen since the Crémieux Decree of 1870, could help France to complete the dissemination of republican values to its Algerian Muslim natives, who remain colonial subjects. Such a position at once affirmed the Jew's own status and elevated the Muslim's.

Twenty-five years later, Jews in France found themselves on the opposite side of a far sharper divide in status. By autumn 1940, in Occupied France, under Nazi and Vichy racial laws, France's Jews became "non- Aryans" and faced growing restrictions on their status and freedom. Stripped of their French citizenship, Algerian Jews were, for the first time since the period of the dhimmi, of inferior legal status to Muslims. While most of the Muslims in mainland France remained French subjects rather than citizens, they had the same legal status as "Aryans."

Under these circumstances, a significant number of the 35,000 Jews from the Levant or North Africa living in France sought to utilize their intimate cultural, linguistic, and religious knowledge of the Maghreb to disguise themselves as Muslims. During a roundup of Jews in 1943, Lucette Bouchoucha was coming out of the Saint-Paul Métro in the heart of the Marais in Paris. Warned by her mother, Bouchoucha had hidden her yellow star in her bag. When approached by an officer and asked her name, she followed her mother's instructions, offering the Arab "Benichou" instead of her real family name, Cohen. When asked if she was Jewish, she said, "Monsieur, I don't know what that is." With that, the officer turned his attention elsewhere and she escaped. Rather than chance an encounter with a Vichy or Nazi agent, many Jews claimed to be Muslim in writing as well. The Algerian Jew René Baccouche claimed that his paternal grandparents were Muslims of Turkish origin who, at the time of the Crémieux Decree, simply registered as Jews in order to gain French citizenship (ultimately this ruse appears to have failed).

The disguise of North African and Levantine Jews as Muslims paralleled the attempts of many Ashkenazic Jews to pass themselves or their children off as Christian. Both practices constituted survival strategies. Yet these Mediterranean Jews' choice of camouflage also reflected how deeply Islam had marked their background. It displayed intimate familiarity with Muslim linguistic and religious conventions, food, clothing, and surnames. Such knowledge attested to these Jews' multifaceted identities. As French citizens who retained vital links to the culture of the Islamic world, most had long operated in both the colonial and the native spheres. Their choice of disguise, however, acknowledged that Muslims and Jews now stood on opposite sides of the new racial barriers erected in Occupied France.

A final snapshot of Jews and Muslimness in France comes from the period of the Franco-Algerian War (1954–1962). In the March 1956 issue of the Revue du FSJU (the precursor to L'Arche), Algerian Jewish leader Émile Touati advocated for the need to welcome Algerian Jewish immigrants. He did so in large part by painting a picture of Algerian Muslim difference. While acknowledging that Algerian Muslims sometimes migrated for the same reasons as Jews, Touati drew several contrasts between the two groups. The Jewish immigration, he claimed, was "Francophone," but most Muslims spoke little or no French. Unlike Muslims, Algerian Jews did not differ so markedly in their daily habits from French citizens of the métropole. French Jewish organizations stood ready to welcome Jewish immigrants, whereas "nothing comparable" existed among Muslims. Most Algerian Jews lived in cities; the majority of Muslims were rural, mainly from the mountainous region of Kabylia. Further, he noted, Jews generally brought large families, wanted to stay in France, were middle class, and had at least small sums of money to build their own enterprises. Muslims, by contrast, usually arrived as single men, for transient reasons, from agricultural settings, and could only do unskilled labor.

To be sure, Touati's assessment reflected certain realities. Yet treatments like his also expressed a clear message, intended for the French Jewish community and the larger metropolitan public: Jews from the Maghreb, especially Algeria, were already Frenchified to a great degree; they could adapt quickly and bring vital cultural, economic, and demographic resources. Muslims lacked these attributes. One should not confuse the two. Whereas massive Muslim migration could provoke legitimate concerns, one had nothing to fear from Jews. Such a depiction implied a static view of Jews, Muslims, and their places in the republic.

These brief historical examples have shown the complexity of periodic attempts by Jews in modern France to create greater closeness or distance between themselves and Muslimness. We have seen that Muslimness served three primary functions for Jews: as an element of cultural commonality; a convenient foil for claims to true Frenchness; or a survival strategy. For Jews in France, then, Muslimness played a more important, multifaceted role at an earlier date than scholars have previously estimated. Moreover, such historical precedents extend farther back in time, and across the Mediterranean. From the 1500s to the twentieth century, numerous Mediterranean Jews acted like veritable shape-shifters. They disguised themselves as conversos, acted as intermediaries between Europe and the Islamic world, or wore Muslim garb in shared Jewish-Muslim ritual events. Thus, as French Jews today navigate their relationship to Muslimness, they are undertaking only the latest in a series of negotiations over identity and status, in France and far beyond.