The Palmach Museum grew out of the need felt by the veterans thirty years after the unit's dissolution to create a central site of memory that would commemorate their dead companions and celebrate their achievements. Why did this need arise after so much time? The answer should be sought in the results of the 1977 elections. For the first time in the history of Israel, the Labor party, which had been the pivot of all coalition governments, lost power to a coalition led by the right wing Likud party. The leaders of the Likud had belonged to the right wing underground organizations that were the rivals of the Palmach, and since the Labor movement through its control of the state imposed its own version of the pre-1948 past, it was to be expected that the new government would try to promote a different narrative in which its own "ancestors" would occupy a central position. The place of honor that the Palmach held in national memory, which had seemed secure because of its identification with the Labor movement, was all of a sudden in danger. (The Etzel Museum was created after 1977, and the process of integrating it into the Ministry of Defense began in 1983, when Moshe Arens was in charge of the ministry. It was fully integrated in 1991.) The sporadic commemorative occasions of the Palmach veterans were no longer adequate to the new situation, and a concerted effort was needed. Later, during the 1980s and the 1990s, another "front" in the war over national memory was opened. A group of "new historians," the most prominent among them Benny Morris, attacked the policies of the Labor movement, the Palmach, and the Israel Defense Forces, arguing that they had played an active role in the expulsion of many Palestinian refugees during the War of Independence. The Palmach veterans, then, eventually found themselves attacked both from right and left, and the museum was their answer to their contesting versions of the national past.

The initiative was taken by Yigal Alon, the ex-supreme commander of the Palmach, who had become a Labor party politician, and had served in ministerial functions in several cabinets between 1961 and 1977. After a successful Palmach veterans commemorative ceremony that marked the thirtieth anniversary of the state, he convened a meeting of his fellow commanders in June 1979. In this meeting it was decided to establish a formal association, "Palmach Generation," with the aim to "pass on the heritage of the Palmach to our generation and future generations." The association included some of the most powerful figures in Israeli politics. Three of them, for example—Yigal Alon, Haim Bar-Lev, and Yitzhak Rabin—were Knesset members for the Labor party at the time; the last two had also been chiefs of staff and members of several cabinets between 1972 and 1995, while Rabin was Prime Minister twice (1974–77, 1992–95). Initially, however, with the Likud in power the association had great difficulties obtaining the necessary funding to realize an ambitious project including a museum, a commemorative monument, an archive, a library, classrooms, and an auditorium—the "Palmach House." Only in 1989, when Rabin was Minister of Defense in the second "National Union" government, the Ministry of Defense agreed to allocate a plot it owned near the Ha'Aretz Museum in Ramat Aviv. The Palmach House would be run as one of Israel's military museums, owned and operated by the Ministry.

Because of budgetary constraints, the project envisaged by the association had to be reduced, and only the museum was finally built. After the inauguration, other elements were added, such as a photographic archive and a small library, but the museum still constituted the core of the edifice. The building was designed by Zvi Hecker, a wellknown, innovative Israeli architect, who had won the open architectural competition launched in 1992. He planned a symbolic structure that looked like a military outpost on a frontier: entrenched in the sandstone hill behind it, with some of the outer walls made of rough, grey cement, full of holes, as though they had suffered heavy shelling. The most innovative feature of the building, however, was the sandstone mined on site and fastened in a natural fashion to the large front wall. A similar mixture of authentic material and artificiality also characterizes the exhibition inside the building.

Work on the exhibition began soon after the allocation of the Ramat Aviv plot in 1990, once it was evident that the project was taking off. The team responsible for creating the exhibition was comprised of people who were relatively new to the field and therefore open to new approaches: the chairman of the program committee, Haim Hefer, a Palmach veteran well known in the Israeli entertainment industry as a lyrics writer; the curator, Orit Shaham-Gover, daughter of a famous Palmach veteran writer (Nathan Shaham), who had been a history teacher and studied museology in the USA; the designer, Eliav Nahlieli, who studied design at Bezalel and was later trained at Disney World; a script writer, Yitzhak Ben-Ner, a well-known novelist, who was later replaced by the photographer Udi Armoni; and two historians, Meir Pa'il, a Palmach veteran and a military historian, and Yigal Eilam, who was considered a critical historian of Zionism.

The planning and execution of the permanent exhibition took about ten years, during which the team grappled with questions of historical representation and narrative construction until they finally came up with a solution. Having decided to do away with "authentic" objects and to emphasize the visitor's experience, they developed a unique display that engaged all the senses.

The visit begins and ends in commemorative hall whose walls are inscribed with the names of fallen Palmach soldiers. The main exhibition is described in a brochure produced by Nahlieli's office. It explains that:

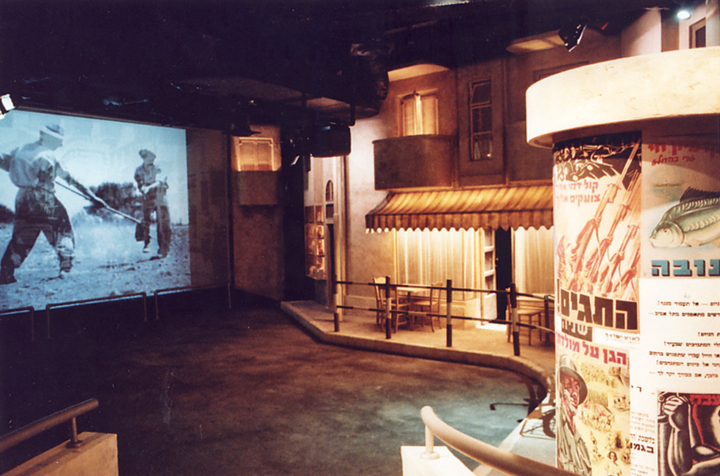

[T]he museum uses the walk-through experience as a unique way to combine education and entertainment in a style known as 'edutainment.' Using a trail along which the audience walks, the museum tells the story in a very dramatic way of a fictional filmed group of young people at a historical crossroad, the choices they made, and their fates, while also giving serious histo-documentary information. The 'story of the group' is projected in full color while the documentary footage is in black and white. The experience, in fact, is more like watching a play while surrounded by the scenery and actors. At each stage, visitors watch three-dimensional replicas of people and situations, which reflect the experiences and landscapes in which the Palmach acted. The dimming of light and sound on one particular stage acts as a cue for the audience to move on to the next scene.

By following the personal histories of ten fictional characters, from their recruitment to the Palmach in 1941 to the 1948 War of Independence, the audience is made to identify with the protagonists, the way one does in a feature film. But viewers also learn of the main historical events of the 1940s, either through the documentary footage, or in an oblique way—when the protagonists take an active part in them. The Jewish illegal immigration to Palestine, for example, is represented in the film through the story of one of the main characters who becomes the commander of an immigrant ship.

The power of the museum stems from its capacity to erase the differences that are characteristic of more traditional history museums. Some of these are mentioned in Nahlieli's text: the differences between education and entertainment, between history and documentation, and between film and theater. To these one can add the differences between historical analysis and commemoration, actor and spectator, past and present, and fact and fiction. Thus the visitor gets a history lesson camouflaged as a moving feature film without realizing that this is only one possible version of the past.

The exhibition tends, for example, to minimize or obliterate the partisan and controversial aspects of the Palmach. The political affiliation of many of its commanders is disregarded, and the circumstances of its dismantlement are absent from the narrative. The deep hostility between the Palmach and the right wing underground organizations, the Etzel and Lehi, is barely mentioned, and the sensitive issue of the expulsion of the Arab population during the War of Independence is ignored. At the end of the exhibition, the film moves from depicting a 1950 commemorative ceremony at the (real) military cemetery of Kiriyat Anavim, where several of the (fictional) heroes are buried, to a magnificent aerial view of today's Israel. A direct connection is thus implied not only between the past and the present, but also between the Palmach and the achievements of contemporary Israeli society, as though one naturally leads to the other.

Avner Ben-Amos is associate professor of education at the Jaime and Joan

Constantiner School of Education, Tel Aviv University. He is the co-editor

(with Daniel Bar-Tal) of Patriotism: To Love the Fatherland (Tel Aviv:

ha’Kibbutz ha’Meuchad and Dyonon, 2004 [in Hebrew]). He is also the co-author, (with Tammy Hoffman) of "We Came to Liberate Majdanek': The Israeli Defense Forces Delegations to Poland and the Military Usage of Holocaust Memory." Israeli Sociology, 2011, Vol. 12, 2, pp. 331-354 [in Hebrew].

Avner Ben-Amos is associate professor of education at the Jaime and Joan

Constantiner School of Education, Tel Aviv University. He is the co-editor

(with Daniel Bar-Tal) of Patriotism: To Love the Fatherland (Tel Aviv:

ha’Kibbutz ha’Meuchad and Dyonon, 2004 [in Hebrew]). He is also the co-author, (with Tammy Hoffman) of "We Came to Liberate Majdanek': The Israeli Defense Forces Delegations to Poland and the Military Usage of Holocaust Memory." Israeli Sociology, 2011, Vol. 12, 2, pp. 331-354 [in Hebrew].