Since my undergraduate years, I have been animated by two master- anxieties. Both anxieties boast a long Jewish pedigree, arguably extending back to biblical times. Both concerns are genuine and supported by historical and contemporary evidence. Taken together, these anxieties motivate my forging close working relationships with protagonists from opposing camps—cultural/religious conservatives in one case, and political progressives in the other.

One of these anxieties centers on massive assimilation in the Diaspora; the other arises from the perpetual condition of antagonism in the Land of Israel. By "assimilation," I mean the effective departure of millions of people with Jewish ancestry from the Jewish group. By the condition of antagonism, I mean the prospect of continual debilitating and dangerous confrontation between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs for decades to come.

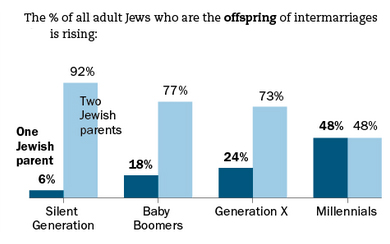

The evidence for massive assimilation of millions of erstwhile American Jews seems undeniable and irrefutable. We can turn to the Pew study of Jewish Americans or, for that matter, any of the recent Jewish population studies—all of them report similar patterns and point in the same future directions.

Among the most critical contemporary population trends (with specific results taken from the Pew study) are the following features of Jews who are not Orthodox:

A. They are experiencing both late marriage and non-marriage, as most (51 percent) of non-Orthodox American Jews 25–39 are not married. Moreover, of Jews in their 40s, fully 18 percent have never married.

B. They exhibit frequent intermarriage, as the individual intermarriage rate for non- Orthodox Jews in 2000–2013 reached 72 percent overall, and 82 percent for those raised Reform.

C. The intergenerational patterns point to low rates of Jewish continuity for the descendants of the intermarried. Of those with one Jewish parent, just 9 percent are raising their children in the Jewish religion. Thus, the vast majority of the grandchildren of the intermarried are being raised as non-Jews or will so identify when they mature.

D. We found demonstrable evidence of low birthrates, with non-Orthodox women averaging about 1.7 children (not unlike their counterparts among well-educated American women). An additional consideration: a good fraction of these children will be raised as non- Jews, a direct consequence of intermarriage.

As a result of these and related processes, the current Jewish population has already experienced a loss of two million adult Jews: Of the 7.3 million adult Americans with a Jewish parent or two, only 5.2 million self- define as Jewish, meaning that about 2.1 million people with one Jewish parent (or two) do not now see themselves as Jewish.

While the non-Orthodox and Jewishly engaged population is on a path to decline, the Orthodox population is booming. In the country, only 10 percent of Jewish adults are Orthodox, but 35 percent of American Jewish children under five years old are being raised in Orthodox homes; while only 10 percent of Jewish adults, the Orthodox constitute an absolute majority (53 percent) of those who in-married in 2000–2013, setting the stage for Orthodox expansion and non-Orthodox contraction in the coming generation.

True, owing to intermarriage and the social acceptance of Jewish identity, those who are partially Jewish and/or episodically Jewish and/or nominally Jewish may be growing in number, augmenting the total Jewish population. But the key concern—my assimilation anxiety—is with the middle of the Jewish identity spectrum, where numerical decline is visible today among children and young adults. In coming decades, the number of middle-aged non-Orthodox Jews who are engaged in Jewish life is poised to drop sharply.

Aside from an axiomatic, if not primordial, commitment to the Jewish identity of every child of a Jewish parent, why should we care if thousands of children of Jewish parents are raised as non-Jews or barely Jews? Of what consequence is it that coming generations contain far fewer engaged non-Orthodox Jews?

The critical concern is that a large Jewish middle is vital to the sustenance of so many major institutions in Jewish life. Most engaged non-Orthodox Jews feel that being Jewish is very important to them, as they say in response to questions on numerous surveys, including the Pew study. They manifest their commitment in affiliative behavior that directly and indirectly benefits the institutions they populate and support. Clearly, Conservative and Reform synagogues depend heavily on these moderately to highly affiliating Jews. So too do Federations, JCCs, numerous Jewish organizations, Jewish cultural events, museums, periodicals, and publications. All these features of contemporary Jewish life—and more—depend on hundreds of thousands of Jews who, while not Orthodox, nevertheless display high rates of Jewish engagement however measured.

American Jewry is contending with the forces of porous boundaries, hybrid identities, and malleable group definitions. Never have American Jews been so accepted, appreciated, and admired. Indeed, of all sizable Diaspora Jewries past or present, they may well constitute not only the most successful and influential Jewry, but also the most romantically loved and most socially desired. If anything, both the internal dynamics of American Jewry and larger cultural forces continue to foster greater and greater integration and, yes, assimilation over generations.

Now think of the sharply contrasting state of Israeli Jewry—as I do, as we all do. Where American Jews are surrounded by non-Jews who love them, Israeli Jews see themselves as enmeshed and surrounded by Arabs who they think, with some reason, hate them. And, what's worse, by any standard of historical comparison, Israel today seems more assured of persistent antagonism with its Palestinian adversaries than before. In the period before the Oslo process of the 1990s, one could theoretically hope for moves toward reconciliation. During the Oslo process, one could hope for its eventual success. But, well after the Oslo process—after more than a decade of repeated waves of violent hostilities with Palestinians and others (e.g., in Lebanon) the prospects for Israelis disengaging from their occupation of the West Bank seem more remote than ever. Nationalist lust, allied with deepening mistrust of Palestinian intentions, is serving to extend Israeli civilian and military control of the Occupied Territories.

With no obvious way—negotiated or unilateral—to leave the territories, and after the years of repeated military clashes, Israel is undergoing several debilitating processes, all of which figure to deepen and broaden in the coming years:

A. Increased antagonism and distrust of Israel on the part of Palestinians.

B. Loss of support and confidence by American political leaders, especially Democrats.

C. Advancing isolation— cultural, political, and economic—in Europe and elsewhere.

D. Increased skepticism among American Jews as evidenced by the pluralities who do not believe Israeli leaders are sincerely seeking a peace agreement— even more so among younger Jews.

E. Greater Israeli investment—economic, political, psychological, and religious— in the Jewish settlement enterprise.

All of these forces, and more, combine to raise the prospects for continued occupation with the West Bank, more frequent and violent clashes with the Palestinian people, greater international isolation, and diminished engagement of non-Orthodox American and Diaspora Jews with Israel. The recent spate of articles proclaiming the end to any prospect for a two-state solution signals perhaps the victory of the Zionist right, but certainly the despair of the Zionist left.

Now, most engaged Jews—and scholars of Jewish civilization among them—tend to strongly focus on one of these two anxieties over the other. Those with more conservative religious and cultural inclinations tend to be more alarmed over the sociodemographic trends that threaten American Jewry; in contrast, more liberal religious and secular personalities seem, at times, almost dismissive of the threats posed by late marriage, frequent intermarriage, and low birthrates. On the other hand, thought leaders and activists on the political, religious, and cultural left tend to focus their existential Jewish anxieties upon Israel's antagonistic conditions.

For me, both anxieties emerge out of the same place: A concern for the creative survival of the Jewish People. An American Jewry with a diminished presence of engaged Jews outside of Orthodoxy is, by definition, less vibrant and vital culturally, communally, religiously, and politically. An Israeli state and society (Jewish, Palestinian, and otherwise) that is permanently and deeply mired in antagonism, alienation, and isolation is— also by definition – less vibrant, vital, and inspiring—both to its citizens and to Jews around the world. Both anxieties derive from circumstances that hold both great peril for Jewish collective life, just as their resolution holds great possibilities for the Jewish future.

The Jewish public and its leadership— somewhat predictably and even understandably—prefer to distort or disregard the threats of assimilation in the American context and antagonism in the Israeli context. Accordingly, the urgent and necessary role of scholars of the Jewish condition, as public thought leaders, is to direct, focus, and shape the thinking of the public and influential persons around these and related matters. Indeed, failing to do so, and even contributing to complacency about the threats to the Jewish People in the Diaspora and in Israel, verges on a failure of professional and moral mission.

Steven M. Cohen is research professor of Jewish Social Policy at HUC-JIR, and Director of the Berman Jewish Policy Archive at NYU Wagner. In 1992 he made aliyah, and taught at The Hebrew University, having previously taught at Queens College, Yale, and JTS.

Steven M. Cohen is research professor of Jewish Social Policy at HUC-JIR, and Director of the Berman Jewish Policy Archive at NYU Wagner. In 1992 he made aliyah, and taught at The Hebrew University, having previously taught at Queens College, Yale, and JTS.