Zamru ’aḥim zamru!

U-va-zimrah ne‘orer ‘am.

Sing, brethren, sing!

Then with song we will rouse the people.

(David Frischman)

Towards the end of my senior year in college I received a phone call from Stanley Sperber. Stanley had been my music counselor at Camp Yavneh in the early 1960s, and was responsible for my transition from a guitar-playing folkie to a student of classical music and an aspiring choral conductor. A few years earlier Stanley had started a youth chorus in Manhattan, dedicated to the performance of Israeli and Jewish music. Eventually they gave their chorus a name: Zamir.

Stanley was phoning to invite me to start a Zamir Chorale in Boston. And so, with naïve enthusiasm and youthful determination, I accepted and dived right in. In October of 1969 some forty students gathered for what would be the first of thousands of rehearsals of the Zamir Chorale of Boston.Neither Stanley nor I was aware that we were actually carrying on a choral tradition. We had assumed that we were bold innovators, creating a new form of expression for our generation—Jewish cultural identification independent of the Jewish establishment. But we were wrong. A few years later I discovered that we were not the first Zamirs.

In 1899 a Polish attorney, N. Shapiro, petitioned the governor of Łódź for permission to establish a Jewish choral organization. Anticipating the hostile reaction with which government officials greeted any gathering that smacked of political sedition, Shapiro asserted that his organization would serve patriotic aims by keeping the young people of Łódź away from the revolutionary and antigovernment assemblies that were poisoning their minds. He ended his petition with the words, "Let these young kids amuse themselves with choral singing, then there will be none of that revolutionary foolishness on their minds." Not only did the governor grant the petition, he instructed the police not to interfere with the choir's rehearsals or to interrupt them in any way from their “patriotic” work.

An amateur musician by the name of Hartenstein was appointed the choir's conductor, but after a few rehearsals it became apparent that someone with more professional expertise would be needed. It was at this point that the eighteen-year-old Joseph Rumshinksy was engaged to become the first permanent conductor of the chorus. Rumshinsky later recalled of that first rehearsal in his autobiography, "When we stood up and started to sing, a holy musical fire was kindled by the first Jewish choral ensemble in the world."

The Łódź choir known as Ha-zamir (or Hazomir) became very successful, and soon inspired branches in other major cities of eastern Europe. In the nineteenth century choral singing had become more and more popular throughout Europe. Enthusiastic amateurs were creating and joining a type of ensemble that had never existed before: the secular community chorus. Some of these choruses were civic organizations, dedicated to performances of the great oratorios. Some were connected to a workplace or to a professional union. Others, like Ha-zamir, were devoted to the expression of nationalist sentiments through music.

Ha-zamir’s anthem was composed circa 1903 by the Warsaw Ha-zamir conductor, Leo Low. The music is in a rousing patriotic style, in the bright key of A major, in a joyous tempo, with sharply chiseled rhythms and rising melodic lines:

The lyrics by David Frischman reflected (as well as inspired) an identity shift among the Jews of eastern Europe: Jewishness could be expressed more comfortably as a nationality than as a religion.

Zamru ’aḥim zamru!

U-va-zimrah ne‘orer ‘am.

Sing, brethren, sing!

Then with song we will rouse the people.

The opening lines of the anthem reveal a secularization of the well-known verse from Psalm 47.

Zamru le-’elohim zameru,

Zamru le-malkenu zameru.

Sing to God, Sing!

Sing to our King, sing!

(Psalm 47:7)

The song is no longer directed to God, the Heavenly King. Now it is a call to social action—it is song that will awaken the Jewish people from its “dark ages” and into the enlightenment. The appeal to “brothers” evokes the ideals of the European Enlightenment, echoing the well-known egalitarian and communal sentiments of the French Revolution, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité,” and of Schiller’s Ode to Joy, made famous by Beethoven, “Alle Menschen werden Brüder.” These musical maskilim were dedicated to the idea that music had the power to inspire people, to create a sense of community and to change their lives for the better.

The anthem continues,

U-va-libot regesh ram.

Va-kam ha-‘am ve-ne’or

Ve-ḥayim be-ḥayim yamir.

Then we will awaken the hearts of the nation

And in their hearts an exalted sentiment.

And the people will awaken and be enlightened,

And will exchange old life for new.

Here again Frischman is riffing off a biblical base. The idea of wakening the Jewish nation from its slumber and seeing the light is found several times in Isaiah.

The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light. (Isa. 9:1)

The mystical sixteenth-century rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz picked up on this idea in his beautiful poem Lekha Dodi (itself inspired by Isaiah 60:1 and 51:9):

‘Uri, ‘uri, shir daberi

Arise, shine for your light as dawned!

Awake, awake, sing a song!

But while Alkabetz was singing to the God of Israel, Frischman’s sentiments were directed to the resuscitation of the Jews as a modern nation.

Heyey ve-ha-ḥayey, ha-zamir.

Brothers, let us sing.

Viva Ha-Zamir, Give life!

The Ha-zamir movement even spread across the Atlantic. In 1914 the first Jewish choirs in the United States were founded: the Chicago Jewish Folk Chorus, directed by Jacob Schaefer, and the Paterson (New Jersey) Jewish Folk Chorus, directed by Jacob Beimel. As immigration of Jews from eastern Europe increased, Yiddish and Zionist choruses began to appear all across the United States. Among them were the Boston Jewish Folk Chorus (1924) directed by Misha Cefkin, the New Haven Jewish Folk Chorus, the Philadelphia Jewish Folk Chorus (1923) and the Detroit Jewish Folk Chorus (1924), both directed by Harvey Schreibman, the Los Angeles Jewish Folk Chorus directed by Arthur Atkins, the American-Jewish Choral Society of Los Angeles directed by Miriam Brada, the New York 92nd St. Y Choral Society (1917) directed by A. W. Binder, the New York Workmen's Circle Choir (1925) directed by Lazar Weiner, the New York Jewish Philharmonic Chorus directed by Max Helfman, the Miami Jewish Folk Chorus (1943) directed by Bernard Briskin, the Newark Jewish Folk Chorus (1928) directed by Samuel Goldman, and the San Francisco Jewish Folk Chorus (1933) directed by Zari Gottfried.

But by the middle of the twentieth century, after the tapering of immigration and with the assimilation of Jews into the cultural fabric of American life, one by one the Yiddish Folk Choruses began to die out. So in the 1960s, even though we were proudly singing Leo Low’s Ha-zamir anthem, Stanley and I and our singers were totally ignorant of the Ha-zamir phenomenon that we were inadvertently reviving.

Today the Zamir movement continues to flourish. The American Record Guide dubbed the Boston branch, “America’s foremost Jewish choral ensemble.” And the New York Zamir Foundation hosts a Jewish Choral Festival every summer that attracts hundreds of singers from all across the content, and has initiated a successful franchise of choruses for Jewish teenagers.

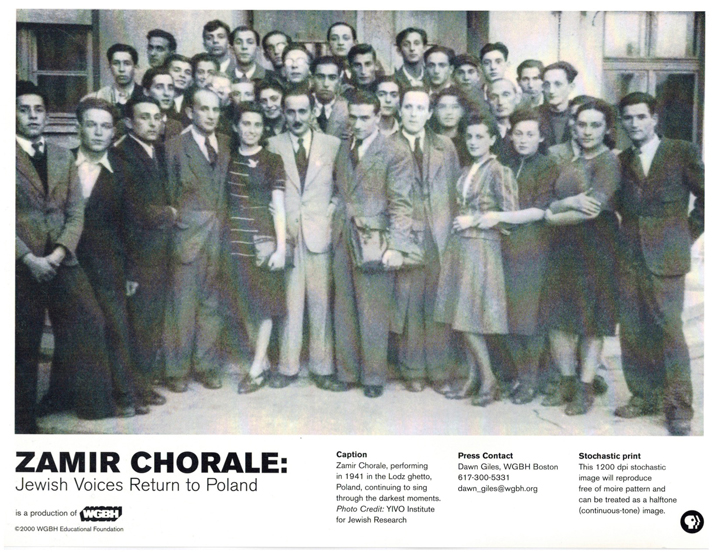

On March 15, 1941, in the Nazi-enforced ghetto, the Łódź Ha-zamir gave what was probably their last concert. I often think of those men and women, of what the act of singing under such circumstances meant for them. In 1999, to mark the centenary of the founding of Zamir, I took my chorus on a tribute concert tour to Łódź, where we were welcomed by the mayor.

The Zamir Chorale of Boston performing the Ha-zamir anthem in the Łódź Town Hall and Hall of Culture: