Those noises—which interrupted my sleep one winter night in 1997—are among the few sounds I remember from the period I spent doing research in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. I was a disciplined doctoral student back then. I spent my days at the Jewish institutions in town and visiting people in their homes, conversing and conducting interviews. Each night, I stayed awake at my computer, recording what I had learned that day.

Today, my notes from those months fill a row of binders that line my office in Cleveland, Ohio. I took time to read through them while preparing to write for this volume on Jewish Studies and sound. I confess that I found little related to the topic. Not only is an auditory description of that 4 a.m. call missing; I have almost no reference to sound at all. This essay explores why sound is often left out of ethnographic description, and what might be gained by including it.

Before beginning, though, I should clarify that when I use the term “sound” here, I do not mean the same thing as music. While I was doing research among central Asia’s Jews (both in Uzbekistan and in their immigrant homes in the United States and Israel), I attended community celebrations, synagogue services, weddings, and mourning rituals. The music I heard at these events was almost all foreign to my American, Ashkenazic ears. I had little context to understand or characterize. Were the vocalists skilled or not? Was the music classical or contemporary? Were the forms amalgams, and if so—then of what? Likewise, I lacked technical vocabulary. I grasped for descriptive words, finding only unsophisticated phrases, such as “bouncy tunes,” and “piercing notes.”

I have made peace with this gap in my writing by acknowledging that others with expertise in ethnomusicology have addressed these issues: Ted Levin in The Hundred Thousand Fools of God: Musical Travels in Central Asia, and Evan Rapport in his recently published Greeted with Smiles: Bukharian Jewish Musicians in New York.

But there is more to be said about sound. One needs no expertise to notice and describe feet shuffling, electricity humming, water running. Such sounds are ever present. Yet they are often ignored, left unmentioned and undescribed. Maybe a phone ringing or a door opening in Samarkand does not sound much different than it does in Cleveland. Unremarkable, perhaps it is not worth writing about. Or maybe the human sense of sound is relatively undiscerning, and our vocabulary about the topic thin, so it seems there is little to convey.

When I asked Nina how a chicken egg is fertilized, she must have thought it funny. “Don’t laugh,” I probably retorted sheepishly, and she likely listened with an encouraging smile, while I developed my question in Russian with some difficulty. “So, does it happen inside the chicken? Or once it is laid?”

Shmuly laughed. He was also entertained by my question. He was one of the young Chabad emissaries from New York. Like me, he was a boarder in Nina’s sprawling compound. He shared an apartment-sized unit with two other Chabad emissaries. Their large dining room windows overlooked the courtyard where they had a view of the garden, the eating area, and the chicken yard.

My situation was different. My room was tucked in a corner, with a small window that looked onto the courtyard’s dark entryway. From here, I missed the spectacle of the hens running away from the large rooster, and his triumphant jumping on them. That’s how the eggs got fertilized, Shmuly told me. The sounds of these activities must have carried across the courtyard. But I was clearly not paying attention.

Early one morning, Nina came into my room and surprised me, holding something unexpected up to my face. It was an egg that a chicken had just laid, warm against my cheek. Sometimes the breakfast she prepared for us included fresh eggs like this one. Other times, she sold or bartered the eggs. Once, she showed me a colorful second-hand dress, which her neighbor had given her in exchange for a few.

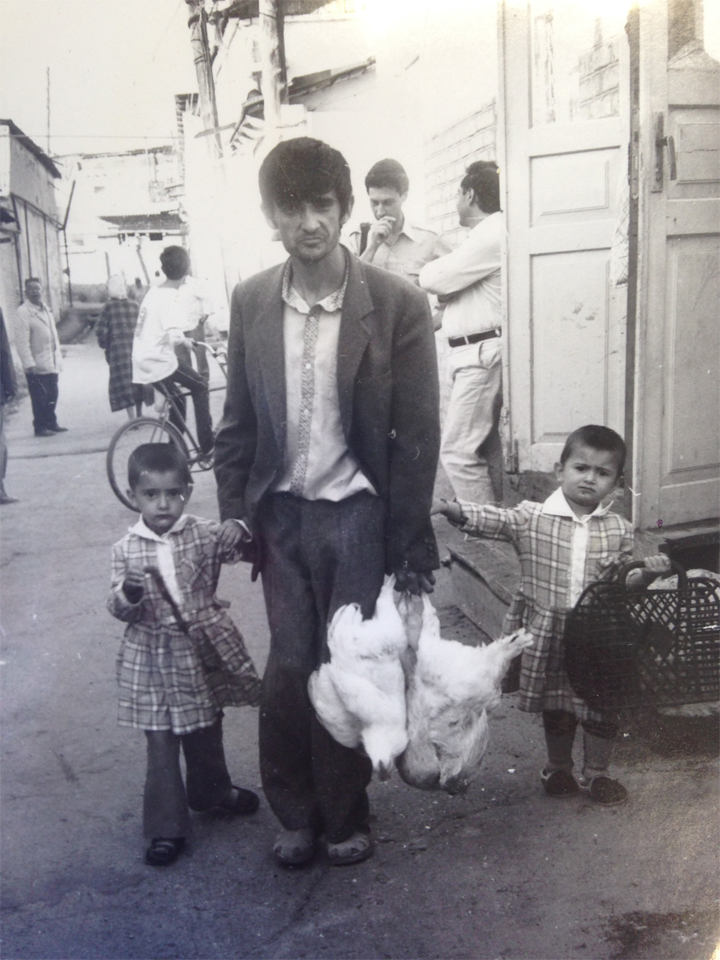

At Passover time, a whole different group of chickens was brought into Nina’s courtyard. They came to be slaughtered at the hands of Levi Forta, another Chabad emissary, who had flown in from Maine for the holiday. By this time—a few years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union—Samarkand’s Jewish population had been drastically reduced as a result of mass migration. Among those who left were all the city’s rituals slaughterers. On occasion, a ritual slaughterer who lived in another part of the country traveled to Samarkand to help out. But for the holidays, when the demand for chicken skyrocketed, this was not enough. Levi—who had spent a year in Samarkand previously—returned to offer assistance.

In the mornings he traveled between the city’s two synagogues. Those who did not manage to catch him at either, knew they could find him at Nina’s place, where he was staying with his friends. Just a few days after arriving, Levi told me he had already killed about 280 chickens. I wish I had paid attention to the sounds of the birds he picked up and dangled by their feet. Did they cry out? I cannot remember.

Nor can I recall the cackles of the chickens, the calls of the mating rooster, or the sizzling of freshly laid eggs in Nina’s frying pan. Yet, as I work to conjure them, these sounds give dimension to my memories of Passover in Samarkand. They call attention to the contours of the local economy, to communal change in the post-Soviet years, and to the cycle of life itself.

As the chickens in Nina’s compound had a set of sounds, the many people who lived there did too. Ours was complicated because we spoke so many languages. Adding to the complexity were our halts and stammers as we crossed linguistic boundaries.

Nina was studying Hebrew. Before the Soviet Union dissolved, she could not read or speak the language. Now, though, with ease of travel to the region, and an influx of representatives from international Jewish organizations, Hebrew could be heard all over the town. Sharp witted and industrious, Nina understood that the language could connect her to travelers—like myself—who might come to her for room and board. By the time I met her, Nina had rudimentary skills, which she was working to improve. I tutored her, poring over her Hebrew textbook, she reading in a Russian Bukharian accent, and me with American tones.

Mostly, though, when the two of us were together I worked on my Russian. She told me about her childhood, her marriage, and her relatives who had emigrated, speaking deliberately so I could transcribe her stories. When she used words I did not know, she repeated them, and I added them to my vocabulary list.

I also needed help with Bukharian. This Persian language (often referred to as Tajik) had been the Jews’ native tongue prior to the nineteenth century, when the region came under Russian control. Sometimes Nina and her husband spoke to one another in Bukharian to discuss household logistics. The long consonants and rush of syllables were song to my ears. But their command of the language was not sophisticated. Nina was unable to help me with the speeches I had recorded on small audiotapes.

For this, I turned to Lolita. Chiseled cheekbones, her hair swept up, Lolita wore stylish shoes and carried herself with confidence. She was so sure of her English grammar, which she had learned in school, that she sometimes corrected me. Lolita’s grandfather was a professor and her uncle was a skilled orator with a strong command of classical Bukharian. With her language skills and access to her erudite family members, she was well suited to help me translate my recordings.

Misha’s face lit up whenever Lolita came to the compound to work with me. He was Nina’s son, who was longing for romance. He knew some English, and used it as swag. “You are beautiful,” he told Lolita, sounding like a Russian Humphrey Bogart. “I love you,” he continued. Serious, and traditionally minded, Lolita had no interest in Misha’s antics. She asked that we move to a separate room to work in quiet.

The country’s national language stood apart from all these others. Since independence, Uzbek (a Turkic language) was becoming dominant in schools, places of work, and on the street. But in Nina’s compound, it was heard only amongst the Muslim university students who were boarding with her. On occasion I used Russian to communicate with them. But they mostly kept to themselves, and I kept my distance, daunted by the prospect of breaking through another cultural and linguistic boundary.

Uzbek, Russian, Hebrew, English, and Tajik; these were the languages of our compound. We tripped over them with broken sounds as we worked to connect with each other in utterances that took effort to deliver and to understand.

On occasion an intruder reminded us that language does not always have this quality. When the lone telephone rang, it could be heard across the courtyard. Was it for me? I wondered each time. Was it a family member with whom I could speak fluidly, in the effortless language of home?

Often such a call would come in the middle of the night, as friends and relatives miscalculated the time difference between them and us, so far away. That’s what happened when my brother called at 4 a.m. to tell me that he and his girlfriend had decided to get married.

I would go home for the wedding a few months later. And then my life in Nina’s compound fragmented into bits of disjointed information, scattered through my notes and letters. Now, by working to recall sound, I have stitched it back together enough to formulate this microportrait of Jewish life in Samarkand in its waning, mobile, post-Communist days. Nina and her husband Boris are still there, but likely not for much longer.