A sonic approach to the study of Judaism can help illuminate, for example, the elusive borderlines between Jewish and non-Jewish spaces that preoccupy so many disciplines. "Sonic" refers to a comprehensive consideration and interpretation of all forms of nonverbal utterances, vocal and instrumental, transmitted orally, graphically, or electronically. Music constitutes but one category of humanly designed sound. Any attentive listening to traditional Jewish rituals discloses a rich palette of meaningful sonic phenomena that should be the concern of scholars. The new concept of "musicalization" describes the process whereas in modernity music has been gradually silencing other significant Jewish sonic formations.

Another essential concept of my proposed agenda is the avoidance of binaries. For example, labeling music "Sephardic" or "Ashkenazic" erases the sonic nuances of place that are so meaningful to performers. Jewish places in the distant past as well as in the present are home to very different Jewish sonic spaces. Speaking about "Jewish musical traditions," then, is another methodological mishap that should be revisited with attention to individual and more localized voices. Sharp binary divisions of repertoires based on gender obliterate overlaps between female and male sonic realms at different historical junctures. Distinctions based on alleged authenticity as opposed to inauthentic accretions disregard the constant construction of "tradition" (in the distant past as well as in the present) through performance practice and innovation.

Another fundamental tenet of my proposal was our massive ignorance of the repositories of sound that are available to research. Academics (and stage performers of "Jewish music," as well) keep recycling materials that were exhausted by previous generations of scholars instead of looking for fresh oral and archival resources. Just as an ear opener: since 2009 when I wrote my original article, research in early Jewish discography has developed dramatically with the location of Jewish recordings in archives of major record companies (such as EMI in London), academic institutions, and private collections. The number of pre-World War II 78 rpm Jewish recordings that survived the vicissitudes of time is breathtaking. Early twentieth-century recordings are not "productions" in the sense of the modern recording industry but rather ethnographical snippets. Past practices that have disappeared can still be audible in spite of the serious limitations of old technologies (of which the three-minute take is the most notable). Who dreamed until recently of hearing piyyutim from 1930s Bombay or a Yiddish theatre troupe from 1906–1910 Lemberg/Lvov? But why look back to the past exclusively? Even present-day music in Jewish communities of Latin America, South Africa, and Australia is marginalized from research by the hegemonic centers of Israel, the United States, and western Europe.

Not only do sound recordings from the distant past or the present await scholarly evaluation; copious annotated sources are still utterly overlooked. For example, the magnificent Birnbaum Collection of Jewish music at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati that was made available to the scholarly community in its fullness after its modern cataloging in 1979 is hardly consulted. Perhaps the current project of digitization of this collection will stir more interest in it.

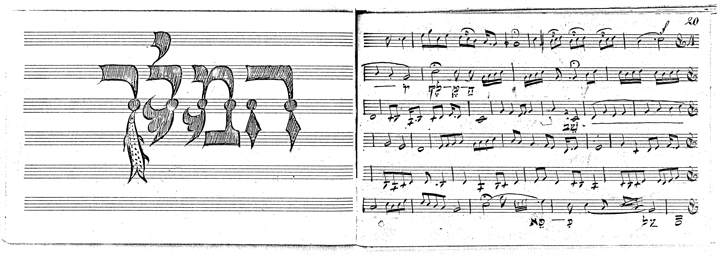

![Alexander Eliezer Neswizski, Ha-mitpalel: Yakhil rezitativim be‘ad [sic] h . azzanim u-ba‘alei tefillah li-tfillot ha-yamim ha-nora’im. fol. 6b–7a, Vilna, 1903.](http://perspectives.ajsnet.org/wp-content/uploads/Seroussi-3.jpg)

Finally, music is a field where Jewish modernity displays its trials with distinctive intelligibility. The crisis of "tradition," the challenges of nationality, the yearning for lost places, the commodification of identity, all can be heard or read through music. To illustrate: if writing music from right to left is a visual metaphor of musicking by modern (European) Jews as Jews and for Jews, we can locate it in unexpectedly disparate contexts: the pedagogy of a rural instructor of liturgy (Mayer Levi of Esslingen) from mid-nineteenth-century southwest Germany; the autoethnography of an early twentiethcentury cantor (Alexander Eliezer Nezwisky) from Pruzhany in the Grodno Governorate of the Russian Empire; and, around the same time, the Hebrew-centered musical agenda of a fervent Zionist Jerusalemite (Abraham Zvi Idelsohn), arguably the "father" of the very modern concept of "Jewish music."

One can listen to Judaism without necessarily commanding the jargon of Musikwissenschaft. Music can be mystifying, but one should not mystify music as an intractable form of communication that is of no concern for nonmusicologists. Musicologists of the Jewish are avid readers of most Jewish Studies disciplines. The time has come for the Jewish Studies community to take Jewish soundscapes into thoughtful consideration.