When I was five years old, my mother began an extramarital affair. We were living on a hilly street in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district; it was the early seventies—a swinging era. My mother was born in Tel Aviv to industrious but insolvent German-born Jewish parents. My father had a typical American Jewish background; he came from the Overbrook section of Philadelphia. The man my mother took up with was seven years younger than she and, among other things, a Connecticut WASP.

Faithless. Faithlessness. Infidelity. Disloyalty. Betrayal.

These words have uses in both the marital and the religious realms. They show us something about our habits of mind, our blurring of boundaries, how quickly we draw comparisons between how we treat those we are intimate with and how we behave in the face of the divine. In the Bible the language of marital infidelity is used as a metaphor for Israel’s infidelity to God, its whoring after foreign gods. In my childhood home it was never clear what was a metaphor for what.

My father discovered that my mother was having an affair after about two years. At this point my father left the house and my mother continued with the man whom I now referred to as “my mother’s boyfriend.” My mother and he stayed together in rather turbulent fashion for another decade, at which point they got married and then promptly divorced a week later. There were endless discussions of the relationship, repetitive words that passed between them in the kitchen at night while upstairs my brother and I turned up the stereo, pretending we were the new rhythm section for Kiss.

Fixed in my mind is an image of my father leaving our house, walking down the stairs. Is this the moment he left for good? Notice his slow, deliberate gait, his eyes rising to find the car, his face turned away in silence.

One of the ways I reacted to my father’s absence was to teach myself about baseball. I’d lived long enough to know boys were supposed to know such things. I started reading the sports section in the San Francisco Chronicle. I learned to parse the box score, a series of numbers, abbreviations, names, and odd phrases that could summon into existence the previous evening’s game. How wondrous. Every day I wore a black Giants cap I’d found in the woods near a playground. It was a personal form of piety that I enacted to prove, I suppose, that I was now claimed by larger forces.

At night I listened to Giants games on the radio. The hum of the stadium told me there was a place where people were awake at night, paying attention. The announcer was named Lon Simmons. He was a WASP to be sure, with a deep, boozy voice, and all the time in the world to recount distant meetings with baseball greats in “the clubhouse.” I was lulled to sleep by tales that meandered through American towns. St. Petersburg, Shreveport, Bristol, Corpus Christi. I used his signature phrase for calling a home run—“way back, way back … tell it goodbye!”—when I batted around a tennis ball with my friend Pat McGee.

As for my mother’s boyfriend, he was afoot on another sort of odyssey. Having lived the first two decades of his life as Craig Van Collie, it was time for a change. One day in the early years of his affair with my mother he announced that henceforth he would be known to the world as Shimon. Nobody considered it a matter much worth pondering, certainly not around the “Dancer’s Workshop” on Divisidero and Haight, where he and my mother first met and where he performed defiant snake dances in the nude. Names were fungible in San Francisco circa 1975; identities were transmutable. (My much older half-sister later had a child with a man named Dire Wolf; my father’s third wife would change her name from Linda Berger to Lila Esther.) And so my mother’s boyfriend became Shimon, a name redolent in his mind (so I’m guessing) with bronzed men on a kibbutz, soldiers praying at the Wall. Nobody was sure where to place the accent on his new name, but the “sh” was easy enough, and it sufficed to lend him an air of mystery.

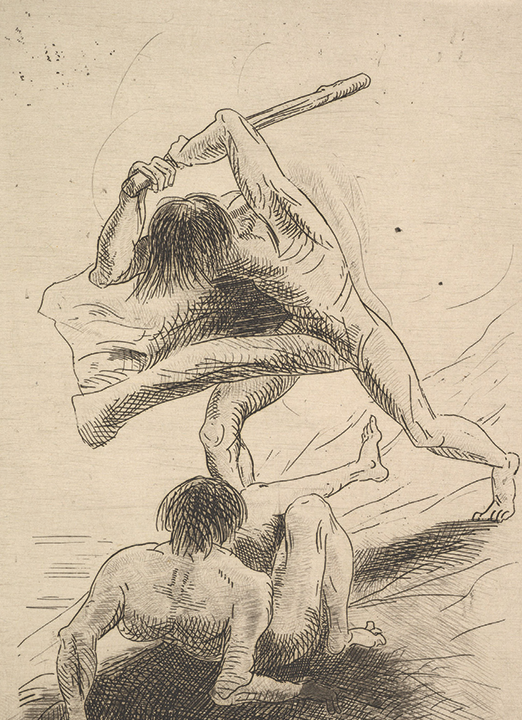

The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art / Open Access.

His full name—and the name he used when publishing articles in Latitude 38, the Sausalito-based sailing and marine magazine where he worked—became Shimon- Craig Van Collie. A cacophony, but a good-faith attempt to keep track somehow of his Connecticut past. And for me the parts of Shimon that held the most promise were those that still cast the glow of Americana: his skills at batting, pitching, and catching, his ability to bait a hook.

One day around the time I was thirteen, Shimon took my older brother and me to Golden Gate Park to play baseball. I must have pitched the ball too close to my brother’s head because the next thing I knew he was charging at me, cursing wildly. After my brother threw me to the ground, Shimon leaned over to me, looking blankly into my face. It became clear that he was not going to stop the fight—fights being, I guess, part of the ways of men or simply not his to interfere with. In an embarrassed voice steadied by a sudden purpose, he instructed me to take my retainer from my newly de-braced mouth and give it to him for safekeeping while scores were settled. I don’t know how long I lay curled up with my hands protecting my face as my brother’s blows rained down.

It is important for me to know whether Shimon regretted my defeat on the ball field. Maybe he hoped I would kick like mad and prove the resourcefulness of the underdog. Maybe he hated my weakness and hoped to cast it out like his own younger, more vulnerable self.

In the lecture class on the Hebrew Bible I now teach at the University of Michigan, I spend a good deal of time on the story of Cain and Abel. There is a print by the nineteenth-century French artist Odilon Redon that is especially poignant to me. Cain is swinging a club, blinded by rage, his body electrified. Abel teeters backwards. Otherwise the scene is completely barren. I show the image to my students with the giddiness of a magician revealing the missing bunny. I am trying to teach them about violence and patriarchy and the failure of the fathers and the cascading betrayals that occur beneath the presumably watchful eyes of the strange God of the Bible. There is more than a little hostility in my voice, as if I’m waging a personal vendetta. But with the patriarchy so dispersed in my life, with the relations between fathers and sons, tradition and invention, power and vacuum, so hard to parse, I can’t be sure whom or what I’m aiming at.