The Jews of antiquity did indeed scatter themselves all over the Mediterranean in significant numbers and with enduring impact. But should one see this, in any meaningful sense, as a consequence of the temple's destruction or the lamentable fate of a people exiled from their homeland and wandering in inhospitable lands with only the distant hope of a "return" to rekindle their spirits?

In fact, Jewish departure from the homeland had a long history prior to Rome's crushing of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Even the Exodus from Egypt had been reversed many centuries earlier. Jews dwelled in that land already in the sixth century BCE, as papyri from a Jewish military colony at Elephantine reveal. The Murashu archive of documents from Nippur in Babylonia from the fifth century BCE attests to Jews in a variety of trades and professions in that city, well after their supposed restoration to Judah. The flood tide, however, came after the conquests of Alexander the Great and the collapse of the Persian Empire in the late fourth century BCE. The arrival of Greeks and Macedonians in the Near East generated the installation of new communities and the expansion of older ones that drew a host of Hellenic settlers and attracted substantial numbers from eastern peoples, including the Jews. As Greeks found the prospects abroad enticing, so also did the Jews. A burgeoning Jewish Diaspora, it appears, followed in the wake of the Greek Diaspora.

By the late second century BCE, the author of 1 Maccabees could claim that Jews had found their way not only to Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Iranian plateau, but to the cities and principalities of Asia Minor, to the islands of the Aegean, to Greece itself, to Crete, Cyprus, and Cyrene. We know further of Jewish communities in Italy, including large settlements in Rome and Ostia. The Greek geographer Strabo, writing at the end of the first century BCE (and he had no axe to grind on the subject) remarked that there was hardly a place in the world that did not possess members of this tribe and feel their weight. All of this occurred well before the demolition of the temple. Even without explicit figures we may be confident that Jews abroad far outnumbered those dwelling in Palestine— and had done so for many generations.

Little of this population shift constituted exile. Nor did it signify mass migration in troubled times to flee oppression. The movement took place over a period of centuries. Some of it, to be sure, was involuntary and unwelcome. Many of those who found themselves abroad had come as captives, prisoners of war, and slaves. Conflicts between the Hellenistic kingdoms of Egypt and Syria in the third century BCE caused periodic dislocation. Internal upheavals in Palestine in the following century generated additional political refugees and enforced settlements. Roman intervention in the Near East accelerated the process. Pompey's victories in Judea in 63 BCE, followed by battles on Palestinian soil over the next three decades, brought an unspecified number of Jews to Italy or onto the slave mart as human booty, the victims of conquest.

Compulsory displacement, however, cannot have accounted for more than a fraction of the migration. Overpopulation in Palestine may have been a factor for some, indebtedness for others. But more than hardship was involved here. The new and expanded communities that sprang up as consequence of Alexander's acquisitions served as magnets for migration. Military service, perhaps surprisingly, proved to be an attractive proposition for Jews. Large numbers of them found employment as mercenaries, military colonists, or enlisted men in the regular forces of Hellenic cities or kingdoms. Others seized opportunities in business, commerce, or agriculture. Our best evidence comes from Egyptian papyri showing that Jews served in the Ptolemaic armies and police forces, reached officer rank, and received land grants. Jews had access to various levels of the administration as tax farmers and tax collectors, as bankers and granary officials. They took part in commerce, shipping, finance, farming, and every form of occupation.

How did Jews conceptualize this dispersal? Was it perceived or represented as exile? Some Second Temple texts, such as Jubilees, Ben Sira, Tobit, Judith, and the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs do echo dire biblical pronouncements about the sins of Israelites and the fierce retaliation of God that issued in uprooting from the homeland and the scattering as penalty for waywardness in times gone by. Some of this may represent warnings to current Diaspora dwellers not to lapse again. But the condition of Diaspora itself in the Second Temple period is not a target of reproach or a source of discontent. It bears emphasis that Second Temple Jews never felt a need to fashion a theory of Diaspora. Those who inhabited a world of Greek culture and Roman power did not wrestle with or agonize over the fact of dispersal. It was an integral part of their existence and a central element of their identity.

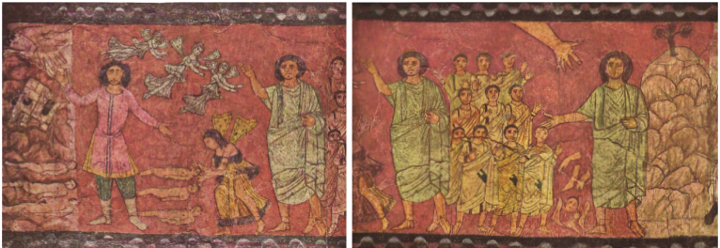

The sense of permanent settlement as migrants rather than temporary displacement as exiles is exemplified by a major development that occurred in the course of the third century BCE: the translation of the Hebrew Bible (or at least the Pentateuch) into Greek. The need for a Greek Bible itself holds critical significance. It indicates that many Jews dwelling in the scattered communities of the Mediterranean had lost the mastery of Hebrew but nonetheless clung to the centerpiece of their tradition. If they were to read the Bible it would have to be in Greek. Their Scriptures contained the record and principles of a people whose roots went back to distant antiquity but who maintained their identity in a contemporary society—and in a contemporary language.

An important question in this regard needs to be addressed. How did migratory Jews relate to the homeland? Adjustment to the circumstances of the Diaspora diffused any widespread passion for the "Return." This did not, however, diminish the sanctity and centrality of Jerusalem in the Jewish consciousness. The city's aura retained a powerful hold on Jews, wherever they happened to reside. Numerous texts acclaim Jerusalem as "the holy city." As the philosopher Philo asserts, even those for whom the place in which they were born and raised and in which their ancestors also dwelled was their patris, still regard Jerusalem as their metropolis. Jews everywhere reaffirmed their dedication to Jerusalem each year through the annual tithe paid to the temple. The ritualistic offering carried deep significance as a bonding device. The historian Josephus proudly observes that the donations came from Jews all over Asia and Europe, indeed from all over the world, for countless years. That annual act of obeisance constituted a repeated display of affection and allegiance, visible evidence of the unbroken attachment of migratory Jews to the center. It also implied that the "Return" was unnecessary.

A comparable institution reinforces that inference: the pilgrimage of Diaspora Jews to Jerusalem for festivals. According to Philo, myriads came from countless cities for every feast, over land and sea, from all points of the compass, to enjoy the temple as a serene refuge from the hurly-burly of everyday life abroad. They were evidently not locked in exile—nor in aimless wandering. The holy city was a compelling magnet. But pilgrimage by its very nature signified a temporary payment of respect. Jerusalem possessed an irresistible claim on the emotions of Diaspora Jews, forming a critical part of their identity. But home was elsewhere.

Gifts to the temple and pilgrimages to Jerusalem announced simultaneously one's devotion to the symbolic heart of Judaism and a singular pride in the accomplishments of the Diaspora. The migrants had made a success of it.

Erich S. Gruen is Gladys Rehard Wood Professor of History and Classics, emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. His publications include Heritage and Hellenism: The Reinvention of Jewish Tradition (University of California Press, 1998), Diaspora, Jews amidst Greeks and Romans (Harvard University Press, 2002), Rethinking the Other in Antiquity (Princeton University Press, 2011), and Constructs of Identity in Hellenistic Judaism (De Gruyter, 2016).

Erich S. Gruen is Gladys Rehard Wood Professor of History and Classics, emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. His publications include Heritage and Hellenism: The Reinvention of Jewish Tradition (University of California Press, 1998), Diaspora, Jews amidst Greeks and Romans (Harvard University Press, 2002), Rethinking the Other in Antiquity (Princeton University Press, 2011), and Constructs of Identity in Hellenistic Judaism (De Gruyter, 2016).