II

I have never wanted to be personally entwined in my own research. Instead, I have addressed the US insularity that has always troubled me by studying the world beyond our borders. The migration whose roots were political exile from Latin America during times of dictatorship and repression has always been compelling to me; I have left to others any discussion of our own country's spotty history as a place of refuge. I eventually came to realize that my research interests have always somehow emerged from the events of my own life, albeit in the most tenuous of ways. I was once a migrant, leaving the United States to live elsewhere, a forever that lasted a mere two years, and not under duress. I have been irritated by bureaucratic roadblocks set in place as a rejoinder to US restrictions on potential migrants from the countries I wished to live in temporarily. But I have never been an exile or a refugee. The few irritations I have endured have served me well; they have concentrated my mind on the lives of others, most specifically political activists exiled from Latin America's Southern Cone. Those interests eventually led me to the stories of Jews whose migration routes included refuge in Argentina and, too often, refuge from that country when it was held in thrall by dictatorship in the 1970s and 80s.

The Argentine junta did not single out Jews as its enemies, but it arrested, tortured, killed, and sent them into exile in disproportionate numbers. Two Jewish survivors of the Argentine torture centers, Alicia Partnoy and Sara Strejilevich, left Argentina for the United States, where they wrote compelling accounts of their experiences that include their captors' grim references to the most ghoulish of Nazi practices. Artists and writers like them have the capacity of transforming even the most dreadful of realities into paintings, art installations, films, music, and literary texts, inviting us into a world that we might otherwise be reluctant to intrude upon. Their work attests to the necessity of artistic expression in the face of brutality. Partnoy and Strejilevich were among the artists and writers who fled from their home country, bearing witness to the abuses of power that sent them into exile. Ironically, Argentina had been a place of refuge for earlier generations of Jews.

III

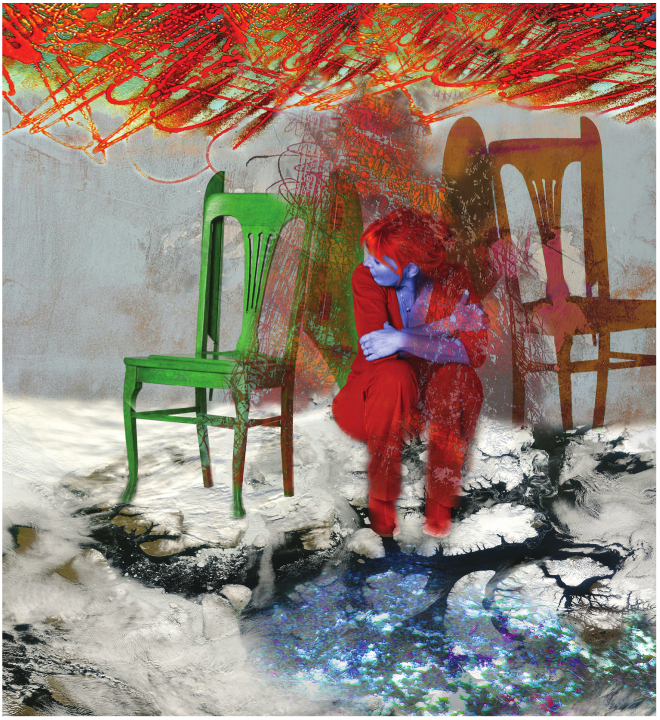

The artist Mirta Kupferminc, Argentine daughter of survivors of Auschwitz, often returns to the memory of loss, uprooting, and wandering that characterized her parents' lives. Now that the United States, which has not been particularly warm to the actual migrants who come across its borders, is exhibiting an overt hostility to them, I return to Kupferminc's art. Her work offers us a profound understanding of the complexity of migration, reaching us through the senses as they meet the intellect. Kupferminc's images cross borders with startling immediacy. In an exuberant body of work that includes paintings, prints, sculpture, video, and performance she captures one of the central paradoxes of migration: that of being simultaneously unburdened, free almost of the gravity that holds us to a place and a history, but also laden with memories and those material possessions we need in order to survive.

Kupferminc's migrants are unmoored; the ties that held them had to be cut when they left home behind. But how to survive without connection, to each other, to a history, and to a place? Those of us enmeshed in the safety and order of home have the luxury of being unconcerned that the common objects we all need to get though our days, and the objects of ritual and of memory that connect us to our history and beliefs, will still be in place as we come and go. Migrants need to guess: What can be left behind? How much can they carry with them? What, of the many things that will be missed, can they leave? Everything that comes along adds to the weight of the migrants' load, even as they are borne along in their lightness.

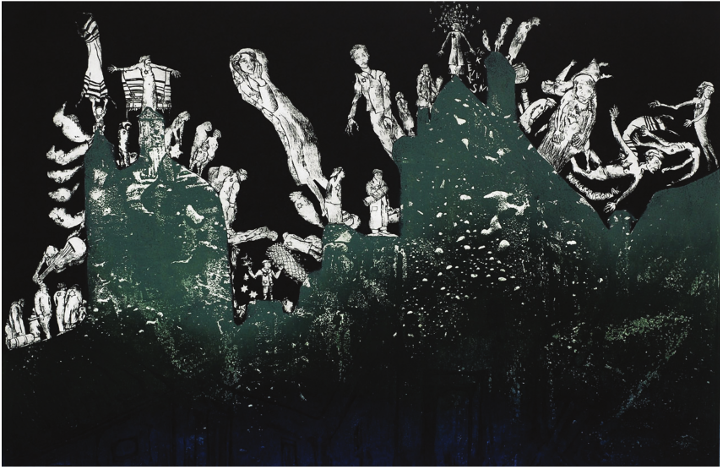

A considerable portion of Kupferminc's work is populated by whimsical figures who wander over a landscape that is sometimes as vast as the planet and sometimes as intimate as a woman's body. In one canvas, that landscape is the back of a tiger, in another it the outline of the artist's own hand. Kupferminc's migrants almost always travel along a clearly defined edge, not enmeshed in a landscape but, rather, forever on its perimeter. They walk, mostly in single file, headed away from a somewhere and toward another-where, but neither their place of origin nor their destination is in sight. In one image, they walk in a never-ending circle around a doll dressed in the richly embroidered garb of a Hungarian peasant (fig. 1). The doll, a gift from her uncle when she first met him, represents a tenuous survival in Kupferminc's symbolic universe: many years after the war her mother discovered that her brother had also survived the Holocaust.

Sometimes one of Kupferminc's figures is upside down or turned backwards. Her migrants may be fanciful, some dressed like carnival performers and others in the garb of Old-World Jews, but all seem radically alone. Some carry nothing with them, while others are burdened by trees complete with their root systems. Some are only part human, work offers us a profound understanding of the complexity of migration, reaching us through the senses as they meet the intellect. Kupferminc's images cross borders with startling immediacy. In an exuberant body of work that includes paintings, prints, sculpture, video, and performance she captures one of the central paradoxes of migration: that of being simultaneously unburdened, free almost of the gravity that holds us to a place and a history, but also laden with memories and those material possessions we need in order to survive. Kupferminc's migrants are unmoored; the ties that held them had to be cut when they left home behind. But how to survive without connection, to each other, to a history, and to a place? Those of us enmeshed in the safety and order of home have the luxury of being unconcerned that the common objects we all need to get though our days, and the objects of ritual and of memory that connect us to our history and beliefs, will still be in place as we come and go. Migrants need to guess: What can be left behind? How much can they carry with them? What, of the many things that will be missed, can they leave? Everything that comes along adds to the weight of the migrants' load, even as they are borne along in their lightness. with plant-like appendages, or fishtails, or the spiky backs of lizards, as if to remind us that migration is about liminality.

IV

Art can cross borders faster even than people; and the deep emotions, sensations, and thoughts that it invokes are inseparable from the lives of its makers and of those of us who are nourished by it. Art matters; Kupferminc and others like her give shape to jagged and chaotic raw experience so that those of us who have not lived it may come to have our own experience in relation to it. It is no coincidence that the current US administration's hostility to migration is matched by its hostility to the arts. Cutting off migration and starving the arts by eliminating funding are of a piece. People will, however, continue to move across borders to save their own lives, and artists will not cease to make art that expresses the human desire for survival and that addresses our need for beauty and our need to represent ourselves for our own sake and so that others may know our stories.

Amy Kaminsky is professor emerita of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Minnesota. Her most recent books are After Exile: Writing the Latin American Diaspora and Argentina: Stories for a Nation, both published by the University of Minnesota Press. She is currently working on a book about the meaning of Jewishness in Argentina. Its working title is Planting Wheat and Reaping Doctors.

Amy Kaminsky is professor emerita of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Minnesota. Her most recent books are After Exile: Writing the Latin American Diaspora and Argentina: Stories for a Nation, both published by the University of Minnesota Press. She is currently working on a book about the meaning of Jewishness in Argentina. Its working title is Planting Wheat and Reaping Doctors.