Most of the studies dealing with the Second Aliyah see it from the point of view of the Yishuv and the Zionist movement and stress the select idealistic groups who came to the country with a fully formed Zionist attitude. It is not surprising that historical memory has enshrined precisely these groups as a pillar of fire that went before the camp. But does this image of young pioneers draining marshes and building settlements, conquering labor and guarding, faithfully reflect the totality of the immigrants who reached the country in those years?

As in the case of Jewish immigrants to the United States, families also immigrated to Palestine. The head of the family came first, examined the conditions in the country and the chances of succeeding there, and only after he had settled down did he bring over his wife and children. A quarter of those who came to Palestine were children up to the age of fourteen, half were fifteen to fifty years old (mainly young tradesmen and artisans), and the rest were fifty and over. These immigrants settled mainly in the large towns—Jaffa, Jerusalem, and Hebron—and a few also went to Haifa. Part of this aliyah were also a large number of people who ended up returning from where they came (yordim). At the beginning of the twentieth century, about 75 to 80 percent of immigrants ended up leaving the country, and between 1912 and 1914, the number of those who left dropped to about 50 percent.

"Run-down, patched up, tattered and torn"

Contemporary testimonies confirm the conclusions provided by the statistics. Many of the immigrants were not people who came because of Zionist ideology, but ordinary Jews who arrived in the country by chance or as a last resort. In those years many Jews in Europe experienced difficult economic circumstances and suffered persecution by the authorities. The decision to immigrate to Palestine was generally not motivated by a longing for the land but by other considerations, such as its proximity to the country of origin and the low cost of a sailing ticket, or by false rumors about conditions in Palestine and the possibilities of buying land there.

In 1905, an information bureau of the Odessa Committee, a Russian Jewish charitable organization promoting emigration, opened in Jaffa. The Jaffa branch of the Odessa Committee was headed by Menachem Sheinkin, who, owing to his position, became one of the key figures dealing with immigration and the reception of immigrants. In a letter he sent in 1908 to Otto Warburg, a member of the executive committee of the Zionist Organization, Sheinkin depicted the human material that came to the country in the darkest colors:

As long as you, the directors, don't attempt to attract capital by the million to Palestine, we are not worth a thing. Our position will not be strengthened by the poor people coming to Palestine on their own initiative. I say, quite the opposite, for our reputation is getting worse from day to day in the eyes of the officials and the general public because of this immigration. What they see is people who are down and out, downtrodden, patched up, with bundles of tattered clothes, the poorest of the poor, who cannot possibly be a blessing to the country, and it gives us a bad name. And if wealthy, respected people, well groomed and well regarded, don't come ashore, in the language of the port the term "Jew" will be synonymous with weak and poor, of little value, the dregs of society, and from there the idea will spread to the other sections of the people. This is the naked truth I have to convey to you as the representative of the information bureau, and every week I could say the same. Everything is static, nothing changes, and nothing is going to change until Palestine receives an injection of capital.

Many of those coming to the country were a far cry from the image of the young pioneer who came to "build and be built." It was a population that made a living mainly from crafts and petty trade. In 1907 artisans in Jaffa came together to found the Artisans' Centre. At first it was a professional association concerned with the welfare of artisans, but it gradually became an organization with national aspirations, which saw the petty bourgeoisie—the artisans—as an important element in the development of the Yishuv in Palestine: "It is undoubtedly a sin where immigration is concerned to give preference to party workers and to give the highly productive and economically well set-up Jewish artisan a lower or neglected status," said Sheinkin, who was the spokesman of a group of artisans of the Second Aliyah and defended their interests.

Shoes of the best kind

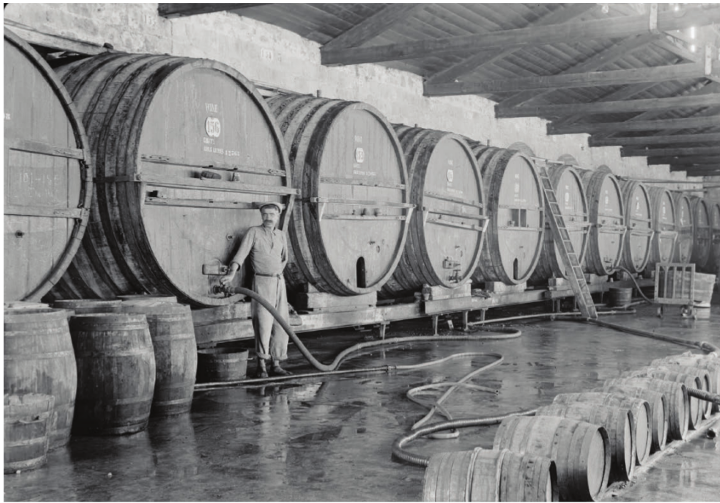

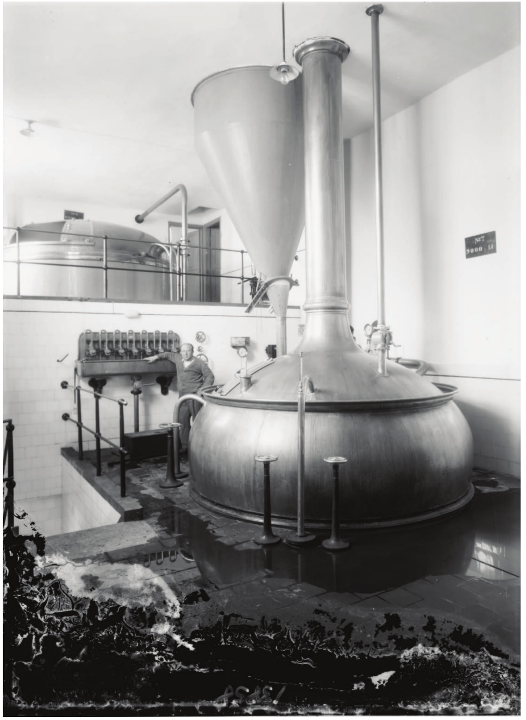

The settlement of artisans in the large towns gradually led to the creation of an economic infrastructure that began to provide new places of employment. Many immigrants were employed in Leon Stein's pioneering metal-casting enterprise in Jaffa. The factory produced corn-grinding machines, railings, iron gates, water pumps and ice-making machines. In 1905 a cork factory opened in Jaffa. The business was managed by two brothers who brought over machines and tools from the Pale of Settlement to make corks "not inferior in quality to the best corks in Europe." This small enterprise employed four workers who were paid two bishliks a day. In that same year, a Jewish couple from Gomel in White Russia opened a sweets factory. A year later they were joined by a partner, the business expanded and, according to them, made "sweets of a better kind than was made previously and the products are not inferior to the best products overseas and sold in shops in Jaffa."

In addition to small factories, there were dozens of little workshops that employed assistants and apprentices. Thus, in 1906–7, for example, a workshop was founded to produce carpets, and there was another that made furniture and wooden toys of various kinds, another that made barrels, and a shoemaking enterprise that employed twenty workers who made "shoes of the best kind." The Kadima workshop for frames made metal bed frames, ovens, iceboxes and English locks, and there were workshops that produced cigarette cases, optical appliances, and goldsmiths' work.

The wave of immigration to Palestine led to the opening of hotels, restaurants, and other amenities. Before the great wave of immigration in 1905, there were three restaurants in Jaffa, but "in the last two years their number increased little by little, until in the summer of 1905 there were six restaurants, and there is another café belonging to two Ashkenazi partners—the first café for Ashkenazis." The hairdressers also prospered: "A few years ago, there was not a single Jewish barber in Jaffa, and only two years ago, in 1905, a Jewish barber came from Russia and rented a hairdresser's shop, and in a short time he attracted quite a number of others." Because of the competition, a few of them had to close.

The artisans fared better than the merchants. Artisans who brought with them the tools of their trade from overseas could easily open a workshop. Merchants, on the other hand, needed initial capital and credit, a knowledge of languages, and an understanding of the laws of currency and commerce. Lacking these requirements, and with the competition of Christian and Muslim merchants, it was difficult for them to succeed.

Jewish girls bathing in the sea

The new geographical location of the immigrants provided stimuli that did not exist in the Pale of Settlement or in America. Businesses run by the local inhabitants in Jaffa closed at a relatively early hour, giving their occupants time to sit in cafés, bathe in the sea, or take an evening stroll along the shore. The pleasant climate and the Mediterranean mentality, so different from the European, led immigrants to wish to imitate local customs. The difference in the make-up of the population in Jaffa created a new situation:

They bathe naked in the sea in Jaffa under the heavens …In the evening, the Arabs flock to the seashore from all parts of the town to gaze at the Jewish girls bathing half-naked in the sea. Each year, the rabbi protests at this act of desecration … but the world carries on in its own way. The Arab girls bathe only at night, in a more modest fashion.

The myth

As noted above, out of all the early waves of immigration to Palestine, the Second Aliyah is said to be the most ideological. Already at the end of the period, its image was formed as a special phenomenon with its own human, social, and cultural character. It is this image that distinguished the immigration to Palestine from immigration to the United States. Thus, the workers of the Second Aliyah became the representatives of the aliyah as a whole.

I have no intention of belittling the importance of the work of the pioneers of the Second Aliyah or questioning their contributions. At the same time, the impact of this group and their influence on the thousands of immigrants who came with them to the country was not seen in the period of the Second Aliyah but only in later years, after World War I. To a great extent, the story of the pioneers of the Second Aliyah resembles that of the Bilu-movement of the First Aliyah, whose image was mainly formed in succeeding generations. It is very doubtful if among the peddlers, petty tradesmen, and artisans there were any that had an opinion about attempts to settle in the distant periphery of the Galilee, Degania, or the Sea of Galilee, an area that was completely unknown to many of the immigrants to the country, and hardly visited by most of them. It is doubtful if they knew about the Shomer organization and its activities, or heard about A. D. Gordon and his teachings. How many of them bought and read the newspapers Ha-po'el ha-za'ir or Ha-'ahdut each week and took an interest in what was happening in the country? Many of them spoke Yiddish and were preoccupied with their material problems and their attempts to survive in the new land.

Palestine, like every destination for many immigrants, was founded by a population of ordinary people who contended with problems of earning a living, an unfamiliar language, and adjusting to the way of life and customs of a new country. In time, they too, in their way, contributed to the development of the Jewish Yishuv.

Gur Alroey is dean of humanities at the University of Haifa. He is a scholar of modern Jewish history and the director of the Ruderman Program for American Jewish Studies. His most recent monograph is An Unpromising Land: Jewish Immigration to Palestine in the Early Twentieth Century (Stanford University Press, 2014).

Gur Alroey is dean of humanities at the University of Haifa. He is a scholar of modern Jewish history and the director of the Ruderman Program for American Jewish Studies. His most recent monograph is An Unpromising Land: Jewish Immigration to Palestine in the Early Twentieth Century (Stanford University Press, 2014).