This next part of the story will probably seem familiar, too: US immigration authorities in San Antonio, who have become particularly vigilant in the wake of recent reports of small aircraft smuggling aliens and drugs, intercept the migrants. They detain the young man and young woman. They also detain the pilot, the owner of the plane, the man from Tampico (who in the meantime has also materialized in San Antonio to deal with paying the pilot) and an associate of the Tampico man—a kind of fixer—who had helped orchestrate the whole plan.

This cat-and-mouse game of migrants and law enforcement in the southwestern US borderlands is a narrative we may think we know well from the news, from heated political debates, from television shows and movies. This particular story, however, took place in 1928. The man desperate to cross into the United States from Mexico was Girsz Silberman, a Polish Jew. The young woman with him was a Russian Jew, Feiga Akselrod.

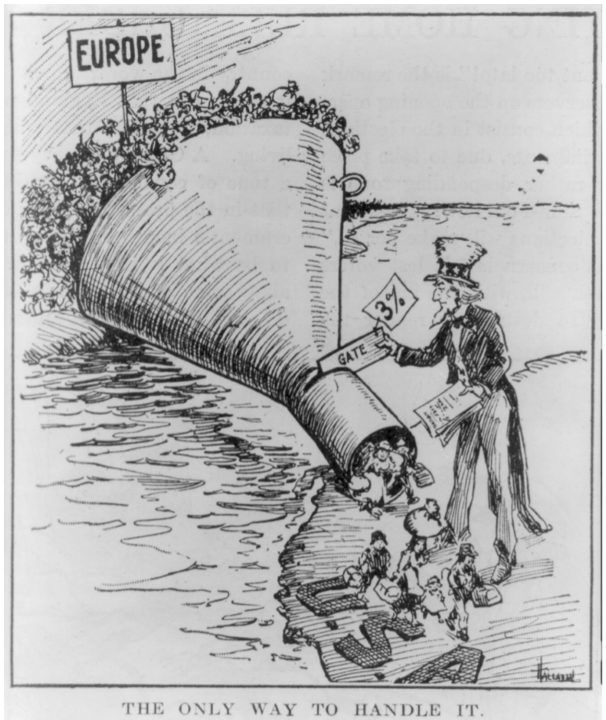

Why did Akselrod and Silberman resort to paying a smuggler to sneak them into the United States? Because in 1921 and 1924, with the nation still riding a wave of World War I–era nationalism and nativism, the US Congress had passed drastically restrictive immigration legislation. These sweeping new laws decreed that most immigration would henceforth be strictly limited according to nation-based quotas. The legislation was designed to keep out immigrants that lawmakers considered racially, politically, and culturally undesirable: east European Jews, Italians, Slavs, and others who had been arriving in great numbers during the century's first decades. The 1924 law, known as the Johnson-Reed Act, also broadened an already-existing ban on the immigration of Asians, widely considered by many policy makers and much of the American public to be the least desirable immigrants of all.

The mysterious man in Tampico to whom the migrants Akselrod and Silberman entrusted their fate represents one channel by which some Jews were able to enter the United States in violation of the new laws. This gentleman was no good-hearted traveler, moved by the young people's predicament. Rather, he was one Samuel Weisstein, a Jewish immigrant from Poland and a naturalized US citizen who had been in the business of smuggling east European Jews to the United States for years. Though Weisstein denied everything when the San Antonio authorities questioned him, the US government already had a thick file on his smuggling activities, which extended to both sides of the Atlantic.

Weisstein was just one of many such "alien bootleggers" who proved a thorn in the side of US immigration authorities in the years after the quota laws. Just as Prohibition produced a lucrative business in contraband liquor, so the new immigration restrictions fueled an extensive underground of unlawful immigration from Europe. Indeed, the human smuggling industry employed some of the same networks and routes used by those in the business of transporting liquor into the nation. The alien smuggling business also drew on strategies established in earlier decades to move Chinese migrants—since 1882 banned almost entirely from entering the United States—surreptitiously into the country.

Just as it is impossible today to know the precise number of people in the United States in violation of US immigration law, so it is impossible to know exactly how many people entered or remained in the nation illegally during the quota years, or exactly who they all were or where they came from. But it is clear from the archival record that European Jews were well represented in this new underworld of illicit migration, both as smugglers and migrants. European Jews still had powerful reasons to come to the United States, despite the new laws. Many had family and friends already here. And in the chaotic years after World War I, many Jews found themselves in dire straits indeed—struggling in war-devastated economies, threatened by new nationalist regimes, or rendered stateless refugees. The desperate and determined, then, often decided to attempt to reach the United States in any way they could. They came by ship, by car, by train, by airplane, and by foot. They paid smugglers to get them across the Canadian border and the Mexican border. They bought fake identity papers in the brisk market for such documents that thrived in Berlin and Warsaw. They stowed away on ships bound for Miami from Havana.

The stories about these Jewish "illegal aliens" and people smugglers challenge some of the classic ways that scholars have understood Jewish migration in the modern age. Historians have tended to describe the time after the quota laws as a time in which "the gates of America were closed" to most Jews. They have observed that the nation's "gates" didn't really open in any significant way until the quotas were abolished by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. It is true that the quota laws were effective, putting a halt to the mass immigration of the pre–World War I years. But the laws did not stop that immigration altogether. The nation's gates never entirely closed to those the laws meant to exclude.

That fact has political implications for our current moment. For starters, it helps undermine the notion that our immigration system ever worked smoothly. Politicians from across the partisan spectrum like to opine that the nation's immigration system is broken. The truth, though, is that there was no golden age of US immigration law, no earlier moment when the system fully achieved its stated goals. The history of real people during those years after the nation implemented its first sweeping immigration restrictions shows that it was clear from the get-go that the American project of controlling borders was never entirely practicable. As soon as there were laws intended to control immigration and national borders, there were people who, just by trying to get where they needed to go, challenged the nation's power to exert that control.

The history of Jewish illegal immigration also challenges the nativist claim that immigrants these days, especially those who come to or remain in the country in violation of US law, are inferior to the good, law-abiding immigrants of yesteryear. This narrative fits neatly with a version of American Jewish immigration history that is firmly established in communal memory—the narrative of the heroic immigrant ancestor who did it "right," coming to this country by ship, seeking freedom and opportunity, working hard and becoming American. But the stories of people like Akselrod, Silberman, and others suggest that immigrants living "back then" went about navigating, or rather circumnavigating, the law much like immigrants any time since, including the present. If they could come legally, they did. But many had powerful reasons to come and no means of obtaining the documents they needed to do it legally. They looked for other ways, despite the risks.