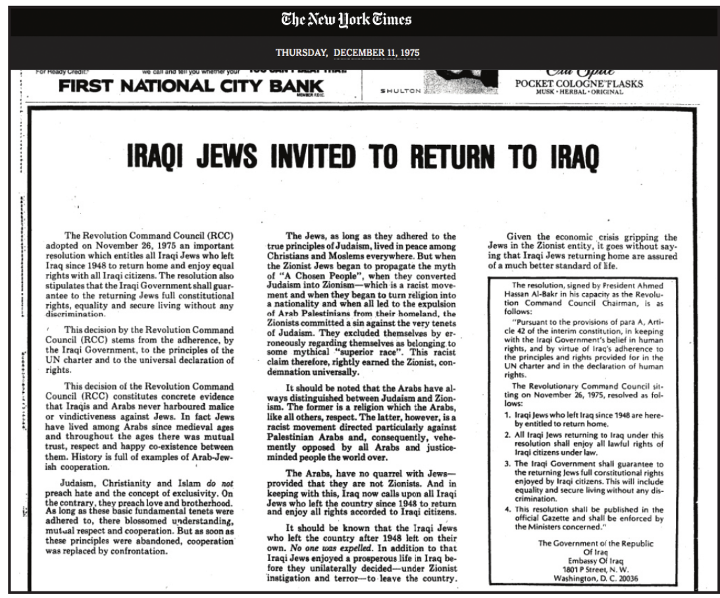

In 1976, Israel announced its annual theme for Independence Day: Israel and the Diaspora. The events following the announcement would prove it to be a topical choice. As a part of the festivities, Israel released its annual demographic report on Israeli Jewish migration. But, with an unprecedented higher rate of emigration out of Israel than immigration to it, the report was no cause for celebration. During an interview on the subject, then prime minister Yitzhak Rabin famously derided yordim (emigrants) as "the fallouts of the wimps." A week later, rumors spread that waves of Mizrahi Jews, particularly immigrants from Morocco and Iraq, would undertake—as state officials put it—"large-scale defections" from Israel. The newspaper Davar reported on hundreds of Moroccan families selling their possessions and packing their suitcases in anticipation of an organized mass migration back to Africa. Iraqi Jewish Israelis could be heard on Baghdad National Radio encouraging Iraqi Jews to follow suit and similarly "return to the homeland." Politicians from Mapai, a centerleft party, formed emergency committees, while mayors of predominately Mizrahi towns scrambled to uncover who or what was behind this. Some thought that Dani Sa'il, a well-known activist in the Israeli Black Panthers, was working with Palestinian militants to fund and encourage repatriation. But a range of Mizrahi public figures, from Mapai politician Asher Hassin to labor union champion Yehoshua Peretz, pointed to another catalyst: anti-Mizrahi prejudice and social inequality. Mizrahi Israelis, facing ethnic prejudice, felt unwelcome in Israel and were prepared to vote with their feet. Dawud Mordukh, an Iraqi Israeli repatriate to Iraq, hit at the core of the issue in an interview: "If the Zionists claim that all Jews that immigrate to Israel are Israeli, then why and how can they logically call this Jew an Iraqi Jew? . . . They should say that this Jew is an Israeli Jew." It was the feeling of alienation, being treated as an Arab foreigner among brethren that caused them to repatriate. These were not opportunistic migrations or attempts at social mobility; they were protests to raise consciousness about social inequality.

Yosef Nawi, for one, was drawn to the possibility of returning to an idyllic past and escaping the deprivation of development towns. The Nawi family, twenty-year residents of Israel, journeyed to Baghdad. There, Yosef held a press conference explaining his decision: "I did not feel that I belonged—not to the government, not to the people, not to the land." Iraq, not Israel, was his Jewish homeland. His migration was an aliyah to Iraq; an escape from an Israeli society he thought to be full of "enough hate [to fill] all the earth." Yosef expressed indignation that Baghdad's remaining Jewish community were acting "like inmates in a sanitarium . . . living at the end of their lives dreaming of Israel and hating the Iraqi government." Yosef's wife, Sa'ida, waxed nostalgic over the Hashemite era of Iraq. She explained to reporters in Hebrew that, "Here [in Iraq], people loved the regime and not like in Israel where everyone waits for [its] downfall." With her Arabic-accented Hebrew, Sa'ida's curious usage of the past tense ("loved the [Iraqi] regime") betrayed her waning affection for Iraq. The cosmopolitan, diverse Iraq that she languished after in the desert town of Kiryat Gat was no more.

Jewish life under Saddam Hussein told quite a different story than the Nawi family. Some years prior to their return, the Ba'ath government executed nine Jews— purported spies for Israel—in a grotesque public hanging celebrated by a crowd of thousands. In response to international condemnation, Ba'ath party spokesmen argued that it was Israel, not Iraq, who oppressed Mizrahi Jews. Nevertheless, flight from Hussein's brutality had reduced the once-thriving Jewish quarter of al-Bataween to a few synagogues and schools. After a year in Baghdad, Yosef Nawi's voice grew increasingly weary during radio broadcasts. Eventually, the family returned to Israel, where Yosef was promptly arrested for treason.

Ya'akov Oved, an Israeli army veteran from Ramat Gan, sheds some light on Nawi's oscillations. Like Nawi, he repatriated to Iraq in 1976 and broadcast appeals to Iraqi Israelis to escape persecution and return to their Iraqi homeland. Yet two years later, Oved left Baghdad for Israel. With stalwart resolve, he used his story of migration to decry discrimination in Israel. His return allowed his transgressive migration to be more politically effective. He explained that he was forced to return after several unsuccessful attempts to obtain asylumseeker status in Europe and the United States. Faced with treason charges and little options, Oved denied being an Israeli and declared himself a "stateless citizen" worthy of the protections accorded under international law.

Perhaps Nawi's and Oved's repatriation— from Israel to Iraq and back—encourages us to look towards the multiplicity of Jewish belonging beyond the boundaries of the nation-state. These transgressive migrations, however small, threatened the raison d'être of the Jewish state: providing a homeland for the Jewish people. In a sense, Mordukh, Nawi, and Oved reworked and subverted the concept of yeridah by flipping its meaning to an emotional descent into Israel. Their yeridah tells us just as much about the nature of the Jewish relationship to Israel and the Diaspora as an aliyah does. It complicates the notion of the "negation of the Diaspora" and forces us to reimagine Israel as a transnational Jewish homeland made up of a wealth of diasporic communities.

Bryan K. Roby is assistant professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author of The Mizrahi Era of Rebellion: Israel's Forgotten Civil Rights Struggle 1948–1966 (Syracuse University Press, 2015).

Bryan K. Roby is assistant professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author of The Mizrahi Era of Rebellion: Israel's Forgotten Civil Rights Struggle 1948–1966 (Syracuse University Press, 2015).