Freedom also had implications for Jews in the United States beyond their own communities. By moving to America, Jewish immigrants from central and eastern Europe took their emancipation into their own hands. Yet Jews, like others who praised America as land of freedom before the Civil War, struggled to come to terms with "unfreedom" in the American South. Slavery had a special resonance in Jewish history, and some Jewish immigrants vowed that as self-emancipated new Americans they had a special obligation to fight for the emancipation of black slaves in the South.

Moravian rabbi Abraham Schmiedl criticized Kompert's call for all Jews to leave for America as naïve. Schmiedl acknowledged that some Jews had good reasons to move to America, but in his eyes Kompert's "Off to America" campaign undermined the struggle for Jewish emancipation in Bohemia. He thus urged Jews to stay and continue to fight for freedom at home, as, indeed, in the summer months of 1848, full Jewish emancipation appeared to be within reach. Other Jews critiqued Kompert on the basis of the American reality, citing the institution of slavery in the United States. Journalist Isidor Busch conceded that slavery was indeed a "badge of shame" and vowed to fight for its abolition. Unlike Kompert, however, Busch moved to America, albeit only after the failure of the revolution in October 1848. After settling in St. Louis (and Americanizing his name), Isidor Bush became a successful businessman. Like many other central Europeans who found asylum in the United States after the failed 1848 revolution Bush was an abolitionist who supported the Union during the Civil War. In St. Louis, Bush is still remembered for his contributions to the Jewish community.

Bush quickly realized that American freedom was not without drawbacks. Immigrants like Bush who invested much time and effort to build Jewish communities faced numerous obstacles, including institutional conflicts. After 1840, more Jews were arriving from different parts of Europe with different cultural backgrounds, establishing separate congregations and associations. Many men started out as peddlers and were constantly on the move. Existing and newly founded Jewish communities experienced a high degree of fluctuation. During the 1850s a growing number of Jews identified with the Reform movement, leading to clashes with more traditionally minded Jews. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise of Cincinnati led the attempt to unite American Jews across the religious spectrum under the roof of a single denomination. During his extensive travels, Wise promoted the benefits of a Jewish "synod" (under his leadership). Several Reform rabbis opposed Wise's project, not least of all the outspoken Baltimore rabbi David Einhorn. Recognizing the advantages of religious pluralism and freedom in the United States, Einhorn and his supporters defended the sovereignty of their Reform congregations. In a small pamphlet published in 1859 in Chicago, "Kol Kore Bamidbar — Ueber jüdische Reform — Ein Wort an die Freunde derselben" (A voice in the wilderness — on Jewish Reform — a message to its friends), Bernhard Felsenthal, a recently immigrated religion teacher from the Palatinate region in southwestern Germany and a friend of Einhorn, explicitly called on Reform Jews in Chicago to secede from an existing congregation. Instead of continuing to fight with their traditionalminded opponents, Reform Jews should form their own congregation because, unlike in the German states, they could. "Do you—and we speak to American Israelites—do you want to dictate to others how they have to pray to their God? Let us not fight, we are brothers! Let us separate!" Immigrant reformers like Felsenthal emphasized the close relationship between the universal Enlightenment ideals expressed in the American Constitution and those in their vision of modern Judaism. The founding of Chicago's first Reform congregation coincided with the Civil War.

The Civil War challenged recent Jewish immigrants to reflect on the meanings of freedom that American citizenship entailed. As they stepped onto American soil, most Jewish migrants had literally emancipated themselves. The war raised the question of slave emancipation. Some Jews, especially in the South and in states along the North-South border, defended the status quo and slavery. Others, invoking the Jewish experience in Egypt, spoke strongly in favor of abolition. David Einhorn famously had to flee from Baltimore to Philadelphia in 1861 because he refused to back down from his fiercely abolitionist position. In many northern cities Jews expressed strong support for the Union. Jewish community leader Henry Greenebaum reminded a large crowd (in German) that Jewish immigrants "owe the Union loyalty, because it gave them social and political freedom, freedom they did not enjoy in Europe." A famous non-Jewish veteran of the 1848 revolution made this point even more poignantly. Colonel Friedrich Hecker, the leader of the Eighty-Second Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, explicitly thanked the Jewish community in Chicago for raising and equipping an all-Jewish company that would join his regiment. In his German address, Hecker drew an intriguing parallel between the struggle for Jewish emancipation in the German states and the duty to emancipate black slaves in the South. Thanking a group of Jewish women who presented him with the regiment's flag, he said: "What I could do in my former home-country to defend the [civil] rights of Jews against intolerance and race-hatred is being repaid today [by you]. Just as emancipation was inscribed on our flags then, this flag will be the symbol of emancipation." It is worthwhile to point out that no Jew had been fully emancipated in the German states until 1862. In that year Baden, the home state of Hecker and several of the Jews present at his Chicago war meeting, became the first German state to fully emancipate its Jewish population.

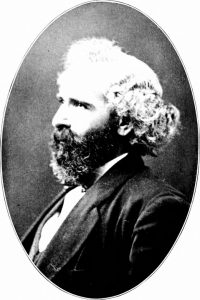

![Emma Lazarus / engraved by T. Johnson; photographed by W. Kurtz. [Between 1878 and 1900]; via the Library of Congress.](http://perspectives.ajsnet.org/wp-content/uploads/6_brinkman_3.jpg)

Before the United States entered World War II in December 1941, State Department officials used Ellis Island to screen groups of Jewish emigrants from Germany and Austria en route to destinations in Latin America and the Caribbean to make sure none were Nazi spies. The restrictive US policy toward refugees was not liberalized until the mid-1950s. Until his death in 1954, the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Patrick McCarran, a fierce anti-Communist and antisemite, successfully undermined attempts to bring larger groups of refugees and displaced persons from refugee camps in Europe and East Asia to the United States. After the war, Jewish survivors and displaced persons were suspected as Communist sympathizers. American immigration restrictions contradicted the ideal of freedom as it was expressed in Emma Lazarus's poem and America's founding documents, because they deprived large numbers of deserving Jewish and other refugees from oppression of access to the "land of freedom."