The foundations for the Jewish aspiration for freedom appear already in the Bible. The Torah relates how we became slaves in Egypt, and that after some four hundred years of servitude, Moses, acting as G-d's agent, led us out of Egyptian bondage through the wilderness and ultimately to the borders of the Promised Land of Israel. We may be well aware that the narratives of the Exodus, Sinai, and the Wilderness did not happen in history quite as they are narrated in the books of the Torah, but we nevertheless celebrate these events in the three major festivals of Judaism, i.e., Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot, as the formative events of the Jewish people.

And yet the Torah narratives also function as a means to reflect seriously upon the challenges and responsibilities that are inherent in our freedom. The Bible is well aware of this issue, insofar as Israel and Judah were small nations situated along some of the most important and lucrative trade routes of the east Mediterranean/west Asian world, and there was no shortage of larger and more powerful superpowers willing to conquer us in order to control the economies and politics of that world.

The Exodus, Sinai, and Wilderness narratives are formulated as creation narratives. Many scholars recognize these narratives as a means typical in the ancient Near Eastern world to explain the formation of a nation and its gods as well as its place in the world. The Enuma Elish or Babylonian creation narrative, for example, functions not only as a means to explain the created natural world order, but also as a means to legitimize Babylon and its god, Marduk, as the founding city and deity of the Babylonian Empire that would bring order into the Mesopotamian world. Similar observations might be made concerning the Ugaritic Baal cycle that legitimized Ugarit and its god, Baal, as the leading city and deity of the eastern Mediterranean coast.

The point is made clear—namely, Israel must be free from Egyptian control, and the Exodus narrative in Exodus 1–15 presents that concern in the context of a creation narrative in which YHWH, the G-d of Israel, battles Pharaoh, the god of Egypt, for mastery over creation and Israel itself. YHWH appears to Moses in the burning bush, the rubus sanctus native to the natural environment of the Sinai, to commission him as Israel's prophet and leader. YHWH employs the first nine plagues, all of which constitute features of the natural Egyptian and Canaanite ecosystem, to challenge Pharaoh and convince him to release Israel. YHWH uses the tenth plague, the slaying of the firstborn, to force Pharaoh's submission and to provide the basis for an early Israelite priesthood in which the firstborn sons of Israelite mothers would serve as priests (e.g., Samuel in 1 Samuel 1–3) before later being replaced by the Levites (see Numbers 3; 8; 17–18). Finally, YHWH creates dry land in the midst of the Red Sea to deliver Israel from Egypt, and then turns the sea against Pharaoh to destroy his army when he attempts to pursue.

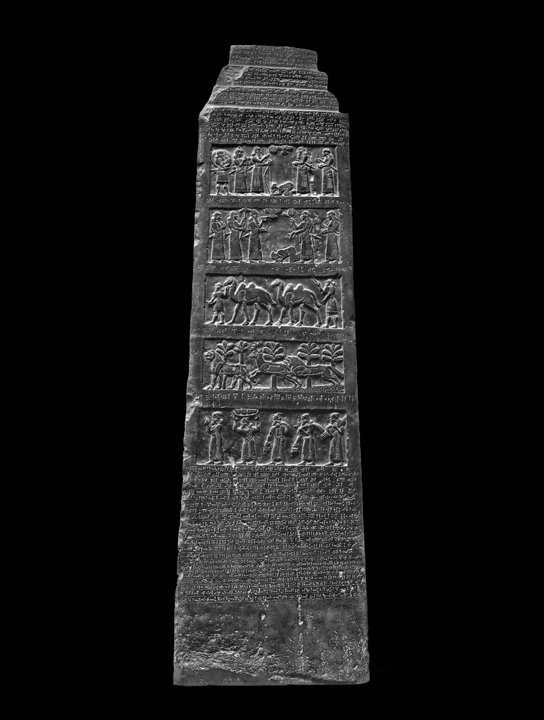

Likewise, the Sinai narrative in Exodus 19—Numbers 10 presents Israel's foundational laws that serve as the basis for organizing a just and holy society in the context of a creation narrative that builds upon the premises of the Exodus account. Mt. Sinai is situated out in the farthest reaches of creation, away from the Land of Israel, as well as the other major nations of the world. Contemporary scholars have recognized how Mt. Sinai has been configured in Exodus 19 as a sanctuary, analogous to the Israelite temple at Shiloh or the Judean temple at Jerusalem, that serves as the holy center of creation in Israelite and Judean thought as well as the locus for divine revelation. The cloud and lightning atop the mountain serve as symbols of divine presence in creation and are replicated in the incense and burning menorot of the temples to symbolize divine presence in Shiloh, Jerusalem, and other sanctuaries. The revelation at Sinai focuses on law, such as the Ten Commandments and Covenant Code in Exodus 20 and 21–23, which respectively state the principles of Israelite law and provide the legal foundations necessary for the establishment of a just, holy, and stable Israelite society. The Ten Commandments are cited by Hosea in Hosea 4, and elements of the Covenant Code are cited by the eighth-century BCE Judean prophet, Amos, in his condemnation of northern Israel in Amos 2:6–16. The Covenant Code was influenced by Mesopotamian legal traditions, such as the case laws found in the Law Code of Hammurabi and the apodictic laws found in Neo-Assyrian treaty texts that Israel adapted from its Assyrian allies beginning in the late ninth century BCE when King Jehu of Israel (842–815 BCE) submitted to the Assyrian monarch, Shalmaneser III (853–824 BCE), in a bid to free Israel from the threat of Aramean invasion, as indicated in the pictorial representation of Jehu bowing at Shalmaneser's feet in the famous Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser. In submitting to Assyria, Jehu did what all national leaders must do, viz., choose the lesser of two evils to ensure the future of his nation in a time of threat.

Finally, we see in the Wilderness narratives of Exodus 16–18, 32–34, and Numbers 11–36 many of the tensions involved in conceiving the leadership of the nation in the Torah. Once again, we see the elements of creation in relation to the provision of water, manna, and quail in the wilderness, all of which represent natural features of the Sinai ecosystem, to support Israel during its journey to the Promised Land of Israel. But we also see the conflicts, such as the account of the Golden Calf in Exodus 32–34. It points to underlying tensions in the relations between Israel and Judah and attempts to explain the destruction of Israel by the Assyrians in 722– 721 BCE and the potential for the destruction of Judah. The Golden Calf narrative in Exodus 32–34 points to Israel's worship of foreign gods in the wilderness, although we must note that the foreign worship is modelled on northern Israelite practice at Beth El and Dan beginning during the reign of Israel's first king, Jeroboam ben Nebat (ca. 921–901 BCE, 1 Kings 12:25–14:20). Although the narratives in Kings condemn Jeroboam as an idolater, it appears that the golden calves were not conceived as gods in northern Israel, but like the Ark of the Covenant in the Jerusalem temple, they served as mounts upon which YHWH was conceived to be invisibly seated. Exodus 32–34 is a Judean, or J, narrative in the Torah that attempts to explain why northern Israel was destroyed. It wasn't because YHWH failed to protect Israel as sworn in the covenant with the ancestors in Genesis; it was because Israel allegedly failed to observe the covenant. Such an experience would then serve as a means to motivate Judah to adhere to YHWH's expectations, under the guidance of the Levites, to ensure their own freedom.

In sum, concern with freedom, particularly the challenges and responsibilities that freedom entails, runs deep in Jewish history and thought, beginning already in the Torah and the rest of the Bible as the foundation of Judaism. May we always protect our freedom and insure its integrity as we continue to develop our traditions to meet the needs of the future.