Debt slavery (2 Kings 4:1; Nehemiah 5:1–5) continued in Hellenistic and Roman times and was, at least theoretically, considered temporary: the creditor could seize the debtor himself and/or members of his family and require them to work for him until the debt was repaid. Stories about the enslavement of indebted families are transmitted in the gospels (Matthew 18:24–34) and in rabbinic literature (Sifre Deuteronomy 26). They point to harsh economic conditions, high taxation, and the exploitation of the poor by the wealthy. Debt slavery was criticized by both the Qumran sectarians and the Zealot leaders of the First Revolt against Rome. At least ideally, it would have been a temporary state in the transition from freedom to slavery and back to freedom again. One may assume, however, that the menace of debt slavery would have occupied the minds of the large majority of ancient Jews on a more or less constant basis: draughts and bad harvests, the loss of farm land, and the illness or death of the householder could quickly endanger the livelihood of a family. Even those who were eventually released from slavery would have to bear the mark of their former enslavement (Y. Horayot 3:5 [48b]: "Do not believe a slave until sixteen generations").

On the other hand, released male slaves, certainly those born Jewish but probably also gentiles raised in Jewish households, could become well-respected members of synagogue communities. Two donors inscriptions found at the Hammat Tiberias synagogue honor a certain Severus, "threptos of the very illustrious patriarchs." A threptos was an abandoned child, usually raised as a slave but in rare cases as a son, in the finder's household. Severus must have been a wealthy person who contributed a lot of money to the construction of the mosaic floor. Not only in Jewish but also in Roman society could freed slaves own a lot of property, especially if they did business for wealthy and prominent masters. Masters could also bequeath property to their slaves, and slaves could receive gifts from third parties that enabled them to purchase their freedom. Even during the time of their enslavement slaves could be very educated and possess a large amount of authority as tutors of their masters' children, as secretaries and advisors, and as business executives.

Rabbinic literature transmits a number of stories about Tabi, the slave of Rabban Gamliel. In these stories Tabi is presented as a disciple of sages, eager to study Torah and observe rabbinic rules (M. Sukkah 2:1). R. Gamliel was allegedly so close to him that he mourned him and received consolations when he passed away (M. Berakhot 2:7). Although Tabi is presented as exceptional and the stories serve to propagate rabbinic values, close relations between masters and their favorite slaves were not uncommon. These slaves would have been treated affectionately and their lifestyle would have resembled or even been superior to that of free people.

The roles of certain categories of free people may have overlapped with those of slaves. At least that is the impression that rabbinic texts provide. Like slaves, women and minors were dependent on the householder: they did not possess property and were subjected to his decisions. Acquiring and divorcing a woman are described in much the same terms as purchasing and manumitting a slave. Wives, especially those of the lower and middle strata of society, were expected to carry out tasks that wives of wealthy households could delegate to slaves (M. Ketubbot 5:5). Some tasks such as washing their husbands' feet clearly expressed their social inferiority. The male authors of the literary sources sometimes ascribe positive values to such functions, presuming that women happily "served" their husbands just as men were expected to serve God. In the Hellenistic Jewish novel Joseph and Aseneth the author has Aseneth, the daughter of Pentephres (Potiphera in Genesis 41:45) and bride of Joseph, state, "And you, God, commit me to him [Joseph] for a maidservant and slave. And I will make his bed, and wash his feet, and wait on him, and be a slave for him and serve him for ever and ever" (Joseph and Aseneth 13:15).

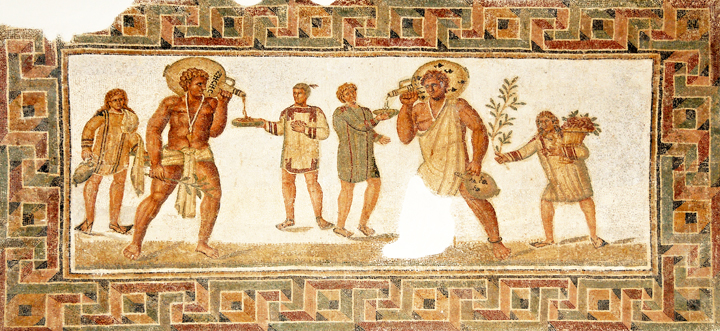

In rabbinic circles disciples appear in servile roles. Just as prominent Roman citizens showed themselves in public accompanied by their servile entourage, rabbis walked about with their students, who carried their utensils to bathhouses, lent them their shoulders for support, and led their donkeys on the road. The "service of sages" (shimush hakhamim) included tasks that slaves typically performed for their masters. Disciples were expected to help their master get dressed, fold his clothes, serve meals and mix wine, and cool him with a fan in hot weather. According to a tradition in the Babylonian Talmud, "All manner of service which a slave must render to his master, the disciple must render to his teacher, except for taking off his shoe" (B. Ketubbot 96a). The practice mentioned at the end was probably considered too humiliating for a freeborn male. By presenting students as their servants, rabbis may have tried to imitate the self-presentation of the male Roman elite. Viewing themselves as an alternative intellectual elite within Jewish society, they needed dedicated servants to gain social prestige.

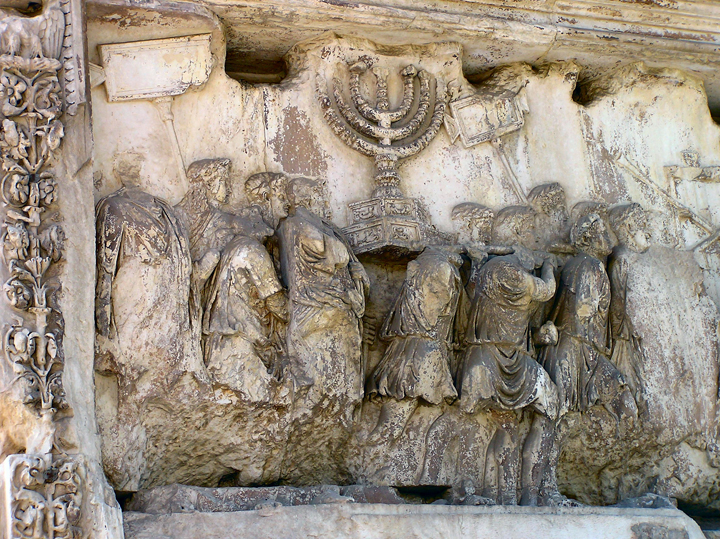

As members of a nation subjected to Roman rule, rabbis and their fellow Palestinian Jews would have been considered to be enslaved to Rome. Enslavement and subjection to foreign rule were associated in the ancient psyche. Josephus already indicates that the enslavement of parts of the conquered population was a common consequence of imperial politics. Yet political subjugation itself was viewed as a kind of enslavement both by the conqueror and the conquered nations. Romans viewed Jews as a "servile" people to justify their subjugation. Jews derided their "enslavement" to Rome when propagating rebellion or self-annihilation (see the Masada story in Josephus). In reality, accommodation would often have been the rule. This phenomenon shows that both strict contrasts between slaves and free people and overlaps and ambiguities between these categories were used ideologically by ancient authors, to justify others' inferiority (Jews in comparison to Romans; women in comparison to men; disciples in comparison to their masters) and to propagate their own identity.

While ancient Jews would have valued political freedom as one of the highest goods, at least the religiously committed among them would have seen freedom as relative only, namely, as the freedom to carry out God's will. If God was one's lord and master and the Torah his set of rules, the definition of transgression would set limits to one's behavioral range. Freedom is always accompanied by constraints, whether these are imposed by the environment, politics, family heritage, socioeconomic circumstances, gender stereotypes, or religious beliefs.