The Bible's introduction contains an acrostic poem that pays homage to the Jewish leadership in Amsterdam, then the center of European Sephardic life, and so, on the surface, affirms the religious primacy of the Old World over the New. Nonetheless, the production of this volume signals a significant shift in the power dynamic between these centers, a shift largely determined by the history of the Caribbean community. Curaçao was established as a Dutch colony in the seventeenth century and became a major trade hub in the Americas. As part of their policy to encourage colonial settlement, the Dutch authorities afforded the Jews of Curaçao great economic opportunities and extensive religious liberties. Over time, the island community had become wealthy enough that it did not need to petition Amsterdam, its mother community, for aid and, as in the case of de Castro, some of its members could commission expensive volumes that required innovative typesetting and great attention to aesthetic detail.

To a certain extent the translation of power from Europe, and Amsterdam in particular, to Curaçao was driven by economic realities, as the island became, in effect, a mother congregation to other New World communities. At first its influence was felt among its Caribbean neighbors, as we find repeated campaigns undertaken by Curaçao's wealthy for the benefit of the Sephardic communities of St. Eustatius, Barbados, and St. Croix, among others. But Curaçao also played an integral role in establishing the earliest communities in North America, with substantial donations made to, among others: New York's Shearith Israel, including the funds for the construction of the Mill Street Synagogue; Philadelphia's Mikve Israel; Nephutsey Israel Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, which would eventually become the Touro Synagogue; and Charleston, South Carolina. These donations to Sephardic communities throughout the Americas continued through the nineteenth century (St. Thomas 1867, Venezuela 1875, New York 1898) and into the twentieth (Panama 1913, Suriname 1928). And as is so often the case, the funds came with strings attached—ritual strings, in this case. Thus, Curaçao's Mikvé Israel's 1729 gift to New York's Shearith Israel was made on the condition that the "ritual and minhag [custom] of the synagogue should [always] remain Sephardic." Letters documenting the subsequent transfer of Torah scrolls and ritual objects to Newport indicate that Curaçao's 1768 donation to Nephutsey Israel was made on the condition that "the Sephardic rite had to be preserved in the synagogue and that [Curaçao's] congregation Mikvé Israel be blessed on Yom Kippur."

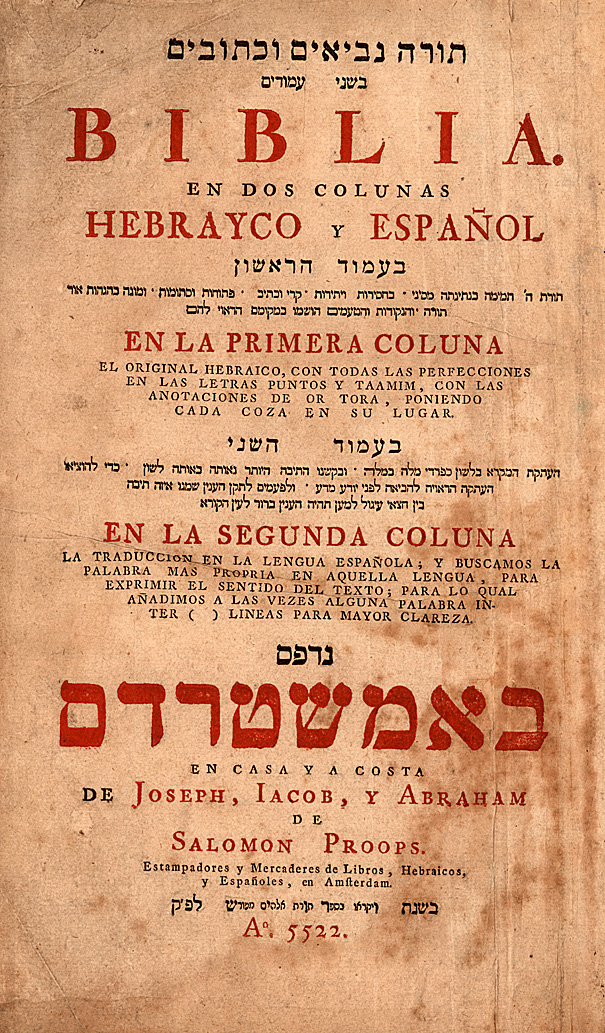

The religious conditions imposed by the Jews of Curaçao indicate that the shift was not merely economic, and in this regard too, the Spanish-Hebrew Bible represented a milestone. As a project initiated by a member of Curaçao's Mikvé Israel congregation for the specific religious needs of its members, it signaled that Curaçao was no longer dependent upon Amsterdam for religious direction in such matters. The specific needs in question involved the emergence of Curaçao as a center for Conversos, many of them coming from Spain, seeking to rejudaize. These Hispanophone Conversos made up the readership for de Castro's Hebrew-Spanish Bible, and so marked one of the first indications of the New World's religious autonomy.

Indeed, the de Castro Bible reveals the complex translation dynamics that emerged in the transition from the Old World to the Americas. Consider the halakhic ramifications of the bald geographic fact that many of the Jewish communities in the Americas were located in the southern hemisphere. Specifically, when should prayers for rain be recited, given the climate of their new environment? The ninth blessing of the Amidah is birkat ha-shanim, a petition for a bountiful harvest. During certain times of the year, a brief statement is appended to this blessing: ve-ten tal u-matar li-verakhah ("and grant dew and rain for a blessing"). Though there are some differences in custom regarding the precise time and duration of the request (e.g., depending on whether the petitioner is in Israel or outside it), it had always corresponded to the seasons of the northern hemisphere and was recited between the Hebrew months of Tishrei (September) and Nisan (April). This arrangement was, of course, altogether inappropriate for Jews in the southern hemisphere, a point addressed in Sefer Torat Hayim, a compendium of responsa by Haham Hayim Shabti, a great rabbinic scholar from Salonica:

A question was sent from a distant land, from the Kingdom of Brazil, which lies at a great distance south of the equator . . . and the days of the year and the order of the year is reversed there with regard to winter and summer, as the sunny season is from Tishrei to Nisan while the rainy season is from Nisan to Tishrei. Rains are needed from Nisan to Tishrei, but not from Tishrei to Nisan . . . Moreover, if rains fall from Tishrei to Nisan, it is very harmful, since the air of that locale is not as fine as our air, we who inhabit the north, and if rains fall from Tishrei to Nisan the air grows moist . . . On account of these reasons they want to alter the order of the blessings with regard to the mention of rain and the petition for rains from Nisan to Tishrei, and not petition from Tishrei to Nisan . . .

After a long discussion of the Talmud, Maimonides, and other (mostly Sephardic) authorities, Haham Shabti concludes that "the aforementioned locale should not mention and petition the rains in birkat ha-shanim, except in the case that they need rains during the sunny season from Passover on."

Religious authority tends toward conservatism, and this is certainly the case with the self-understanding of the earliest Jewish communities in the New World. Their leaders sought advice from European centers of learning, hired religious leaders trained in the old yeshivot, and constantly reaffirmed their fidelity to established authorities. But no translation is absolutely faithful to the original: the encounter with a new geographic, economic, and political reality could not but have ramifications for the religious ideals and practices of the Jews of the Americas.