And yet, I find myself thinking again about Josephus, and in more humanizing terms.

Most of us learn about Josephus not in daily life or ritual but in formal Jewish Studies coursework, so it's worth reflecting on our experiences of introduction. Mine? Sitting in a professor's office in Grey Building, a sunlit office next to the neo-Gothic Duke Chapel. We translated Josephus from the Greek, line by line. There was no biography, no context. We just translated the Greek sentences and talked about grammar. There was a general knowing wave of the arm toward his untrustworthiness. In Religious Studies, a certain kind of liberal scholar is most terrified of the word "apologist." Jewish Studies scholars have for centuries needed to turn somersaults to prove themselves as objective historians, untarnished by their own religious or ethnic leanings. As one of the few figures of overlap between Jewish and Christian Studies, Josephus has taken the brunt of all of this discursive uncertainty. Everyone gains, it seems, by scorning him.

It's also the case that Josephus's biography and his writings are situated at the intersection of cultural conflict and identity, as are many scholars. If you haven't embodied notions of hybridity and the multicultural, if you tend to lean toward singular communities and away from the intellectual imaginarium of a globalized, motion-filled world, then Josephus's complexity, his ability to overlap and live in several worlds, and additionally, his veering away from Jewish militarism won't seem like merits.

If you're able, though, to consider the ancient first century differently, to imagine what it sounded like, to reconsider the complexities of identity, and to consider what the emotional world that created everything from early Christianity to the rabbinic movement may have felt like, then Josephus becomes quite interesting. This is the heart of my historian's transgression: to meet Josephus head on and humanly. Look around. He's the dude with his heart on his sleeve. If you actually read his writing, this becomes easier and easier to see. Josephus has gotten a bad rap for living between two cultures, for not being a pure Jewish rebel. I disagree, really. I think much of our best work comes from living at the margins and in multiple uncomfortable places.

Josephus was born Yosef ben Mattityahu in Jerusalem in the early first century CE. For most of his teens and twenties he was a bit of an aristocratic fop, popping between Rome and Jerusalem, hanging with the ruling-class sons of both cities. The First Jewish Revolt changed everything. Josephus was given a command, and then left his command. He was a moderate, and he was drafted to work as a translator for the Romans.

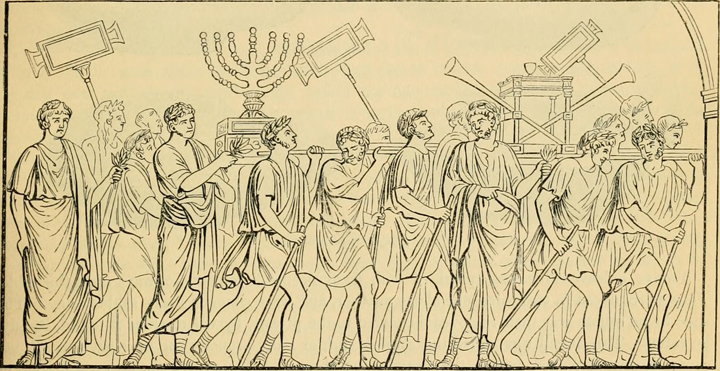

When the war was over, Jerusalem was burning, and Jews from Judea were refugees, displaced from their homes, some taken as slaves. Now in his thirties, Josephus sailed to Rome, and for his work was given a pension and an apartment. Yosef ben Mattityahu now became Titus Flavius Josephus.

After the trauma of the revolt, Josephus was never the same. This is when Josephus became a writer, which he hadn't been before the war. He found a good source for papyrus pages, gathered pen and ink and whatever notes and histories he could find. In his apartment, supported by his Roman pension, he began to feverishly write the history of the Jewish War. He wrote and wrote, unable to move on in life until the words lined up on the page, until the whole bloody, sad story was told. Josephus was no Herodotus, happily meandering through time and space to gather curious anecdotes about humanity. This was history at the hand of a man who married and divorced over and over, never again happy, never again able to relax and live in ease. It is the writing of a man who is wishing his people and places back into life, and grabbing words, one after another, to make it happen.

After The Jewish War was complete, Josephus turned to a much bigger project, a fierce act where memory and historian's passion meet. He would write the history of the Jews, who'd never had their history told in quite this way, especially for the period after the biblical books end. Josephus gathered notes, especially the pages of Nicolas of Damascus's Universal History. Nicolas had been secretary to King Herod in Jerusalem, and had penned copious notes on everything he could.

Josephus wrote two smaller pieces, his Vita, and Against Apion.

Even though he was married and had several children and a nice apartment paid for by Rome, he was never at ease. Some Jews called him a traitor because he didn't want to fight, but I see these years of his life as a fight on other terms. No one in his circle of intellectuals believed as he did that the Jews had much a history to be proud of. They were, again, a defeated and exiled people. Apion was a philosopher and historian from Alexandria, where many Jews lived among the Egyptians, and had, for centuries. Josephus felt that Apion's book History of Egypt slandered the Jews, and he gave voice to what he knew, even if it has sounded to us like meek apology. "The Jews have introduced to the rest of the world," Josephus writes, "a very large number of beautiful ideas." Josephus was not creating the terms of the conversation. He was providing the narrowest path through which the history, presence, lived-ness of the Jews could step, even gingerly, into the historical record, could make it into the centuries ahead.

Josephus's own world closed its ears to the exiled historian's call. Just a few years later, the historian Tacitus finished his magnum opus, the Histories, which includes the Roman siege of Jerusalem and the year 69 in Roman history, a terrible year, in which Rome went through four emperors: Nero, Galba, Otho, and Vitellius, and then, Vespasian, the first of the Flavians. Josephus must have been despondent that his writing couldn't change Tacitus's mind: the Histories used all the anti-Jewish sources that Josephus had tried to discredit.

Josephus's Jerusalem and Judea were destroyed, Jewish people were spread out everywhere, sometimes free, sometimes enslaved. He alone, it turns out, had the capacity to reach into the past and commit the Jewish stories to the written word. He believed in the Judean and Jewish past, in accomplishments and ordinariness, in the specialness of the Jewish Torah and in the unremarkable, just-like-everyone-else, quality of the Maccabean and Herodian royal families. It didn't matter that the Jews hadn't produced philosophers as Greece had or military legions like Rome. They were his people, they'd been destroyed, and it was going to be by his hand that they'd be saved, finally and for all time.