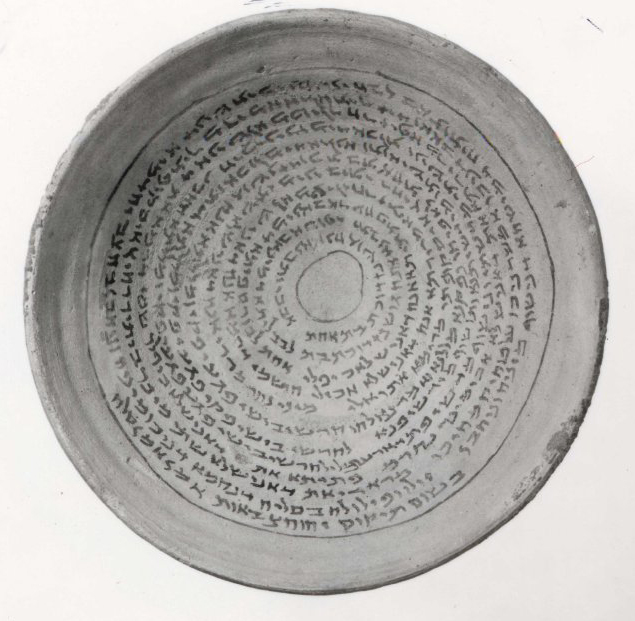

This piece is a thought experiment, showing how one incantation could make sense from a "Jewess" perspective. Incantation texts that are written in the first-person feminine singular are rare and, of course, authorship and identity in ancient texts cannot be established for certain. Other scholars in the field of ancient magic might insist it is far more likely that a male ritual practitioner wrote this incantation for an illiterate and pagan female client. Still, since we will never know the context in which this was written, a second look may prove productive and help us acknowledge the distance between the Judaism of today and the Judaism of the ancient world, which had practices we might reject as transgressive, practitioners we might deem heretical, and a religious vocabulary that borders on the foreign.

Though rabbinic literature serves as the major source for the study of ancient Judaism, most Jews were not part of the rabbinic movement (as the rabbis themselves lament). In late antiquity Jews lived throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond, speaking local languages even as they maintained some distinctive dietary, bodily, and temporal practices. Ancient Jews might have prayed at home or at the synagogue using some Hebrew, but they also went to the marketplace where they spoke other languages, lived in neighborhoods alongside polytheists, and sometimes even shared a courtyard with them. How Jews prayed reflects this shared milieu as well: Jews prayed in Aramaic and unselfconsciously used Greek titles for God like kyrios, commonly used by Christians in their liturgy too.

In this incantation, the client is attempting to defend herself from other sorcerers, their demons, and their spells, and she relies on a combination of sources of power to help her. In the late antique world, there was a spectrum of authority figures to whom ancient Jews could appeal when they prayed or engaged in ritual practices: they could address God directly, pray through the hazzan (prayer leader), approach rabbis, solicit a ritual practitioner, or they could take on an intermediary role themselves as ritual practitioners. Ancient Jewish ritual practitioners were themselves diverse in their approaches to the divine. Some Jewish practitioners, whom we might say were very pious, treated incantations like public prayers and avoided using the sacred name of God in their amulets altogether. Many practitioners described themselves as acting under the auspices of the heavens or in the name of God and the angels. Some used the sacred and taboo name of God (the tetragrammaton) to prevail over demons. Still others invoked angels as witnesses. A few Jewish ritual practitioners, relying on their own authority and power, likened themselves to angels.

The self-characterization of these Jewish practitioners needs to be understood in terms of how pagan ritual practitioners went about their work: polytheistic incantation texts from the Greek Magical Papyri often show the practitioners describing themselves as divinities. To list a few examples: "I am Hermes"; "I am Anubis . . . I am Osiris"; "I am Adam the forefather"; "I am Horus . . ."; or the Coptic invocation: "I am Mary, I am Mariham, I am the mother of the life of the whole world. . . ." These ritual practitioners assume the voice of heroes, forefathers and foremothers, and gods. It seems likely that assuming these voices gave the practitioners confidence or a sense of authority with which to heal, protect, or serve their clients.

One of the distinguishing features of Jewish incantation texts is that Jewish practitioners only aspire to the status of angels and even then they make sure to affirm God's singular supremacy. In one popular formula from the city of Nippur, a practitioner begins an incantation by describing himself as an angelic figure of fire: "Again I come, I, Pabak bar Kufithai, in my own might, on my person polished armor of iron, my head of iron, my figure of pure fire. I am clad with the garment of Hermes . . . and the Word, and my power is in him who created heaven and earth." This practitioner does not assert that he is an angel, let alone a God, but does assert his power and that he acts under God's auspices. We have here an example of Jews sharing a linguistic formula with polytheists, but adapting it to Jewish sensibilities.

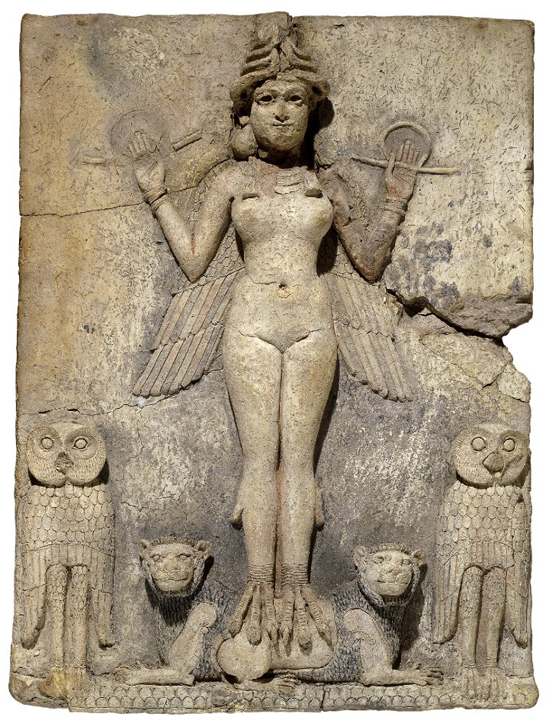

Angels in the biblical and Jewish imagination were gendered masculine (see male visitors that turn out to be angels in Genesis 18–19; seraphim who cover their "legs" in Isaiah 6:1–6; or women who need to be modest because of the angels in 1 Corinthians 11:10). With this principle in mind, to whom could a Jewish female ritual practitioner liken herself if she wished to describe her own authority? Perhaps local goddesses that she saw in the world around her:

I, Gusnazdukht daughter of Ahat, am sitting at my gate, resembling Bablita.

I, Gusnazdukht daughter of Ahat, am sitting in my portico, resembling Borsipita.

We encounter Gusnazdukht sitting at her gate, a liminal space both public and private, and she is describing her confidence by comparing herself to local Babylonian goddesses: Bablita and Borsipita. Notice that she only states that she resembles these goddesses. She does not call on the goddesses to help her or identify with them. The fact that she compares herself to goddesses, rather than angels, may be an example of a woman using the cultural vocabulary available to her to describe herself in feminine, yet also powerful terms. Gusnazdukht looks elsewhere to accomplish what she cannot do with Hebrew liturgical or ritual vocabulary.

Ioana Latu recently published a study in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (Latu et al, 2003) showing that simply hanging pictures of successful female leaders in a room significantly increased women's confidence and improved their performance in challenging tasks. Might divine feminine figures outside the Jewish tradition have inspired women in antiquity in a similar way, even if they did not worship them? Was there a space for cultural conversation that did not amount to transgressive idolatry? This incantation may depict one woman navigating these considerations within the parameters of ancient ritual practices.

After detailing her struggle and triumph over her adversaries, at the end of the incantation, there is an appeal to a singular god, signing off with the formula "in the name of Tyqws yhwh Sabaoth, Amen Amen Selah." Tyqws is an obscure name: here it's joined with the Jewish God's name and the epithet of Hosts. Is Tyqws a cryptic cipher for 'Adonai? Or is it an entirely different being, the ruler of all demons? Is this an appeal to the God of all demons and heavenly hosts—an example of cultural and religious hybridity? An acknowledgement that God rules over good and evil beings (Isaiah 45:7)?

The easy solution would be to exclude this incantation from examination from a Jewish perspective, to write it off as written by a male Jewish ritual specialist for a non-Jewish client. This might be termed cautious, but it is not necessarily objective and leaves the text opaque. Good scholarship opens up understanding; it does not close it off. In this case, the amulet presents an identity that is not easy to reconcile with our preconceptions, but perhaps that is what makes it so important for the understanding of Jewish identity in antiquity.