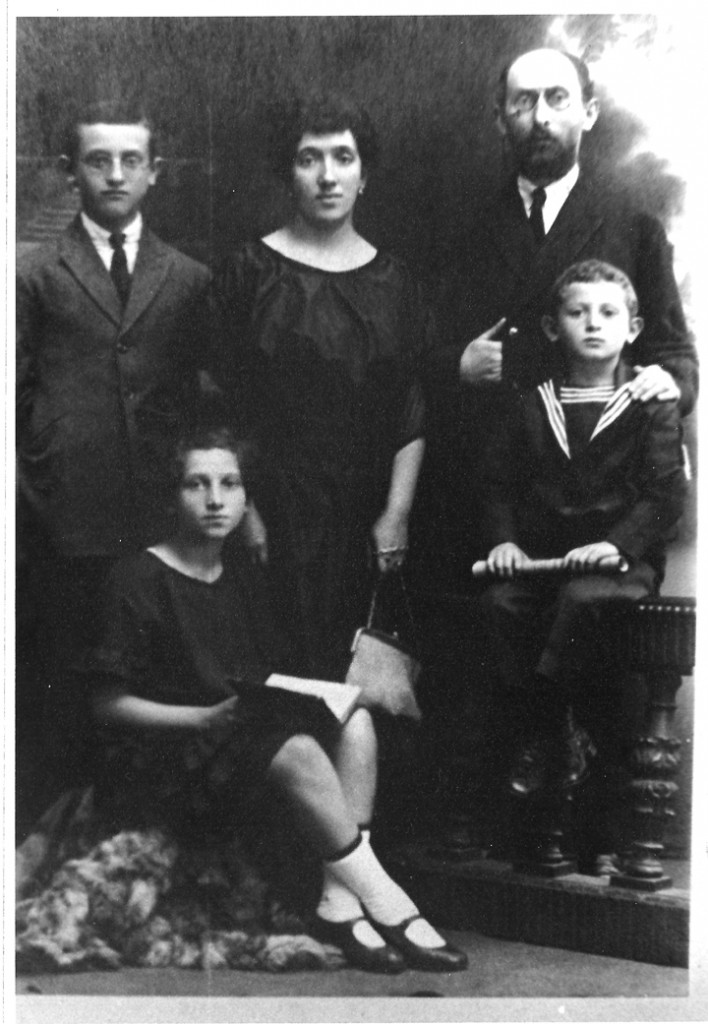

Her declaration was hardly born of a well-conceived ideology or of conscious intent to overthrow the religion of her ancestors. She, like my grandfather, was in most respects a thoroughly Orthodox Jew, nominal followers of a pietistic Hasidic sect. Yet, in the first decades of the twentieth century, the winds of radical change began to blow through the 10,000-strong Jewish community of Wloclawek, some 200 kilometers northwest of Warsaw. Despite his Hasidic leanings, my grandfather joined the Mizrahi, the party of religious Jews who supported the Zionist movement. He was also instrumental in creating a Hebrew gymnasium in the town. The renaissance of the Hebrew language, so often associated with secular Zionism, did not seem to him to contradict the dictates of the Jewish religion.

These halting gestures toward modernity left a deep impression on my father. In the interwar period, when Polish Jews embraced a host of conflicting ideologies he and his sister joined Hashomer Hatzair, the Zionist youth movement that espoused socialism and a romantic return to nature. His younger brother gravitated in the opposite direction, also to Zionism but instead to the Revisionist Betar, the hard-line nationalists who wore military uniforms and rejected social revolution. Both movements, despite their differences, were staunchly secular, viewing the Jewish religion as complicitous in the sufferings of the Jews.

This admittedly anecdotal and personal account of one family's journey provides the thematic backdrop for my recent book, Not in the Heavens: The Tradition of Jewish Secular Thought (Princeton, 2010). For many, rejection of religion in favor of a secular life was not the result of ideology but instead a response to the dislocations of modernity: secular education, urbanization, migration, and the breakup of traditional society. Thus, my maternal grandparents abandoned traditional Judaism almost without reflection when they immigrated to America in 1912. It was not so much a revolution of ideas as it was the flight from traditional communities, rabbinic authority, and the daily routine prescribed by Jewish law.

It is the intellectual history of Jewish secularism that forms the subject of my study. While the ideas of Jewish secularism did not create this revolt, they gave it its characteristic expression. For, although Jewish secularization was but one chapter in the broader story of modern secularism, it had its own features that it owed, at least in part, to the Jewish tradition that it sought to overcome. The dialectical relationship between the Jewish religion and the tradition of Jewish secularism mirrors what has happened to secularization theory in general. The old secularization theory that argued for a complete rupture between modernity and premodern tradition has come under serious challenge. It is now evident that the secular incubated in the world of religion, much as the word "secular" itself was a product of the medieval Christian Church.

In the Jewish context, one can argue that this process owed much to textuality: those educated in the four walls of the yeshiva might turn the texts of tradition against the tradition. Such was the case with Moses Maimonides who became, for many secularists, the precursor of a rationalist approach to nature and religion, an argument that necessarily took Maimonides out of his medieval context. Such was also the case with the texts of those who rebelled against tradition, most notably Baruch Spinoza, whom Jewish secularists turned into "the first secular Jew." With Maimonides and Spinoza, such secularists could build an intellectual lineage, a counter-tradition of their own. Or, as Isaac Deutscher put it in his famous essay, "The Non-Jewish Jew," "The Jewish heretic who transcends Jewry belongs to a Jewish tradition."

This counter-tradition of Jewish secularism must therefore be seen as joined at the hip with the religious tradition it rejected. One way to describe this dialectic is by showing how secular thinkers appropriated the three traditional categories of God, Torah, and Israel and filled them with new meaning. The God of the Bible, who already lost his personality in the medieval philosophy of Moses Maimonides, became nature in the renderings of Spinoza and his disciples. The medieval Kabbalah provided the source for another modern vision of God, as "nothingness" or "void." Secular readings of the Torah—starting with Spinoza—stripped scripture of its status as revelation and turned the Bible into a historical, cultural, or nationalist text. And secular political thinkers, led once again by Spinoza, redefined "Israel," rooted though it was in old notions of the Jews as a nation, in the context of modern, political ideas about race, nationality, and the state. Other secularists preferred to see Israel in cultural terms, focusing on history and language. As a modern concept, "culture" came to take the place of religion. In all of these ways, secular Jewish thinkers sought to bury the religious tradition with the very tools of the tradition.

While it may sometimes seem as if the story of secularization is a narrative of the world we have lost, secularism is not only a negative—it is also an effort to fashion a new identity out of the shards of the past. The secular tradition I have tried to describe differs in some measure from Deutscher's "Non-Jewish Jews" since it rests only on those whose writings engaged substantively with the metaphysical, textual, political, and cultural dimensions of the Jewish experience. Many of these authors may not have consciously regarded themselves as contributing to such a tradition, although some surely did, but taken collectively, they created an intellectual lineage counter to the religious tradition called "Judaism." And while my grandmother would have surely found most of these ideas profoundly alien, they nevertheless gave expression to the new reality that her own small but significant gesture of rebellion helped to create.

David Biale is Emanuel Ringelblum Distinguished Professor of Jewish History and Director of the Humanities Institute at the University of California, Davis. He was educated at UC Berkeley, the Hebrew University and UCLA. He is the author of five books, the most recent of which is Not in the Heavens: The Tradition of Jewish Secular Thought (Princeton University Press, 2011). He is also the editor of Cultures of the Jews: A New History. His books have won the National Jewish Book Award three times. Most recently, he won the UC Davis Prize for Undergraduate Teaching and Scholarly Achievement. He is currently the project director of an international team writing a history of Hasidism.

David Biale is Emanuel Ringelblum Distinguished Professor of Jewish History and Director of the Humanities Institute at the University of California, Davis. He was educated at UC Berkeley, the Hebrew University and UCLA. He is the author of five books, the most recent of which is Not in the Heavens: The Tradition of Jewish Secular Thought (Princeton University Press, 2011). He is also the editor of Cultures of the Jews: A New History. His books have won the National Jewish Book Award three times. Most recently, he won the UC Davis Prize for Undergraduate Teaching and Scholarly Achievement. He is currently the project director of an international team writing a history of Hasidism.