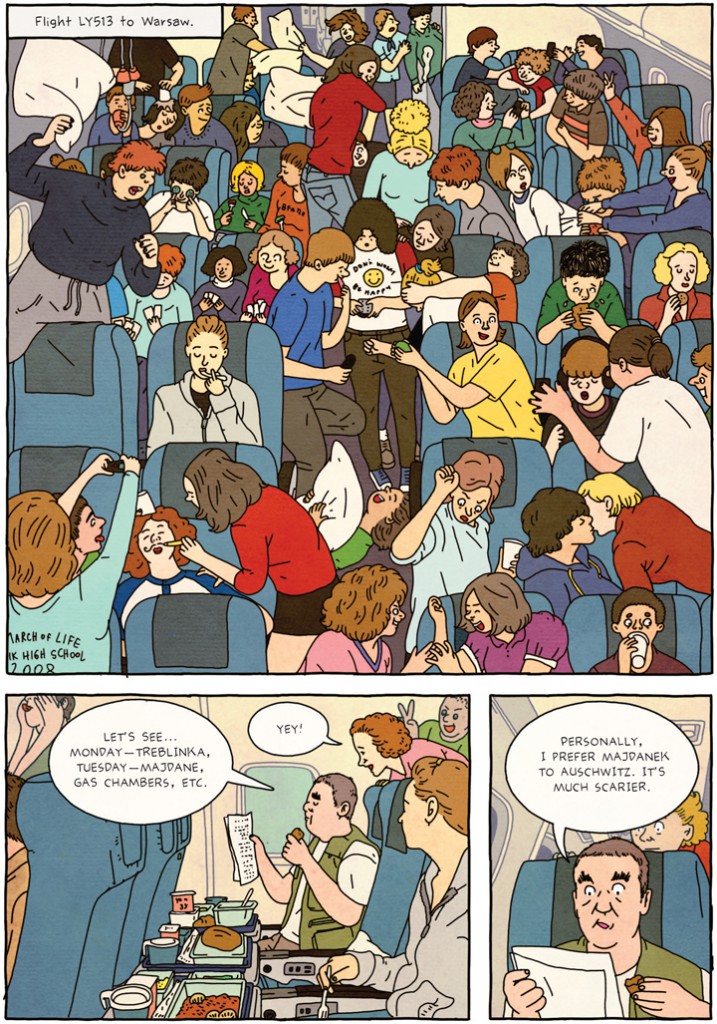

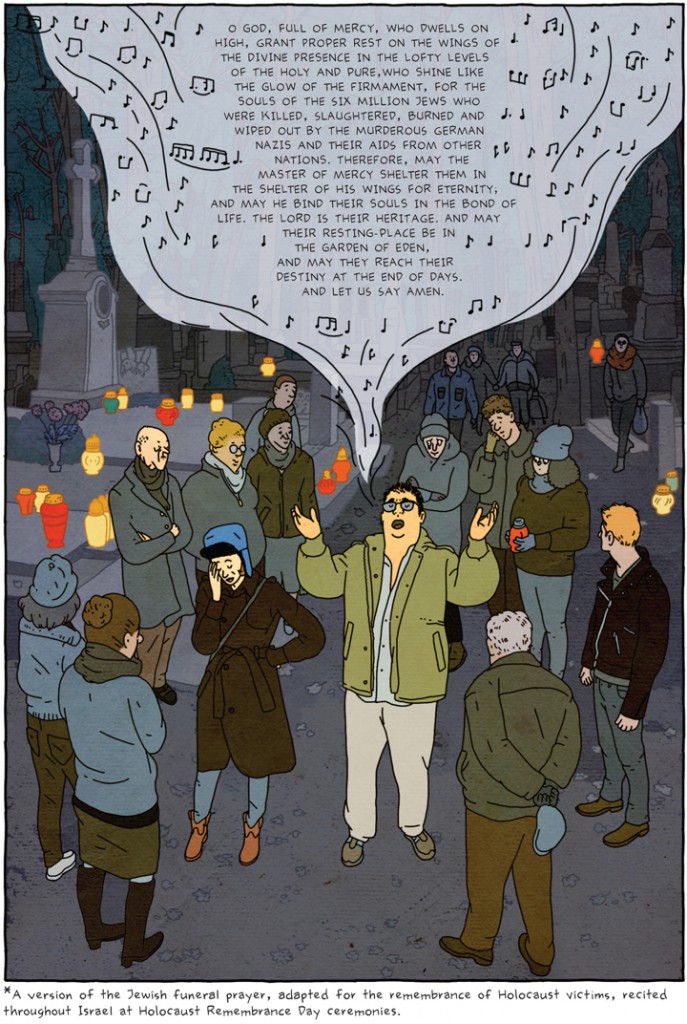

In between these two broad, dramatic nods to History—especially the memory of Polish-Jewish experience and the Shoah— Modan's narrative takes place in the more expressly mundane sites of everyday life: cafes, streets, restaurants, cinemas, public transportation, hotel rooms and bathrooms, and other domestic interiors. The search for "the property"—itself caught up in the legal and social machinations of history—provokes strong emotions for Regina, and readers witness how she painfully registers the past within the city's streets: when a taxi takes her back to the address where she grew up, Modan frames scenes outside the car window in sepia to depict the diverse and dynamic street life of her memory—a visual echo of Shimon Attie's moving public installations, where slides of prewar Jewish life were projected on contemporary buildings. Both offer palimpsestic renderings of eastern European Jewish experience. But perhaps it takes a graphic novel, with its playful respect of different discursive realms, to create an intertextual frame for a palimpsest, and to make it meaningful. Once a place has entered history, it's difficult to retrieve it in any other way, even for those who lived it. In Modan's book, Warsaw as a space in the Jewish historical imagination meets the counter-space of Regina's personal past; this latter, more interior experience of place seems poised to supersede, or at least critique, those monumental, curated sites marking Warsaw's Jewish past, especially the ghetto tours and recreations of "Jewish Warsaw" that Mica happens upon. Within the space of the graphic novel, text and image conarrate Warsaw's Jewish places, interrogating the limits of their historicity and their ability to endure—within the interior space of "the property"—beneath the illuminating yet blinding glare of history's grand narratives.

This year I read portions of The Property together with family and friends during the seder on Passover's first night. Passover is one of those times of year in which space and place seem paramount. I mean here not only the recitation of texts containing tangible particulars of place (e.g. the experience of slavery, the tactility of the plagues), but also the seder itself as a kind of space, created through a self-contained set of exercises and rituals, performed in innovative and free-wheeling fashion in a home, or home-like setting. While the text itself is relatively static, commentators have intervened and commented through the Haggadah's visual dimension. Who among us has not dawdled over the illustrations during a particularly long stretch of Magid? Pictures are among the Haggadah's most effective teaching tools; witness, for example, the changing attitudes and attire of the "Four Sons" in different historical periods.

The creative proliferation of the Haggadah as nearly a genre unto itself in contemporary Jewish culture seems to me somehow consonant with the transnational emergence of the Jewish graphic novel as an important site of cultural transmission, especially regarding difficult memories (the New American Haggadah [2012] and Maus [1991] being well-known examples of each). In both instances, narrative text and visual images are framed by inventive layouts and experimental font cases, creating works that push against—and at times entirely erase—the distinction between secular and religious cultural forms. The relation between The Property and the Haggadah as an image-text is especially poignant, given the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which began on the first night of Passover, April 19th, 1943. While the Haggadah and the seder turn our attention repeatedly towards the monumental events of Exodus and after, through the cyclical refrain "in every generation," Modan's vivid narrative and delicate images urge us to remember those more everyday details, without which freedom is inconceivable: a cooked meal, a shared embrace, a family secret.

Passover, of course, is famously not like every day. But it does ask us to examine, even overturn, our routine ways. The prompt "what makes this night different from all other nights" leads to an examination not only of difference, but of sameness—that quotidian habit or object that is so ingrained, so "natural" a part of "all other nights," that it takes an entire week (or eight days) to produce a state of hyperawareness regarding those very practices we may usually take for granted: like, to take a random example, eating bread. The Passover seder is an immersive, studied attempt to replace the everyday with difference, with the hope of reminding ourselves, for yet another year, of the precious sameness of everyday places.