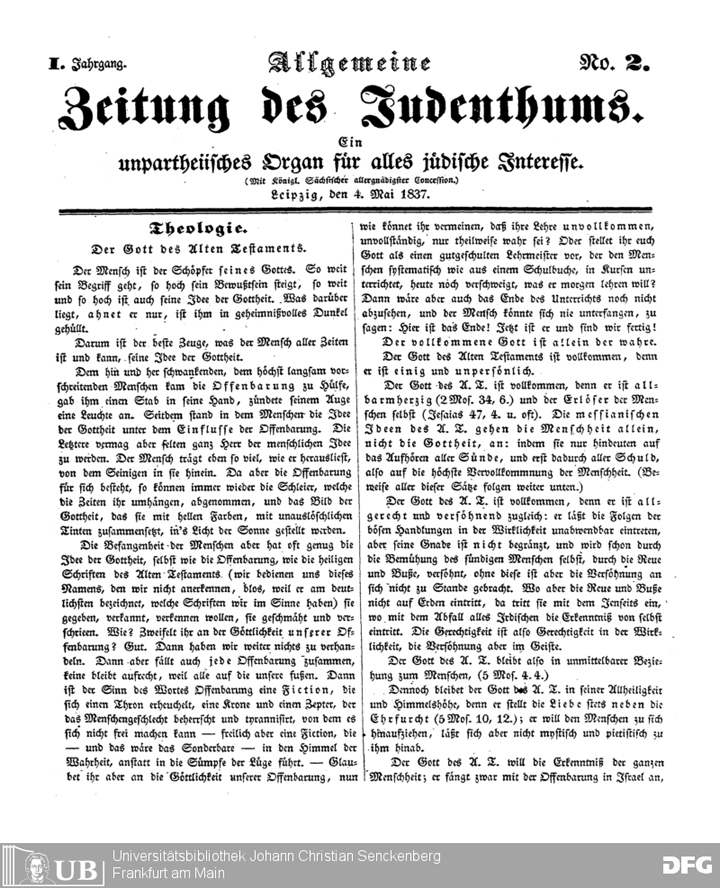

Historical fiction was one of several genres cultivated by nineteenth-century German Jewish writers who wrote in German, primarily if not exclusively for other Jews. Two of the main authors were Ludwig Philippson and Marcus Lehmann—rabbis who also wrote novels in German for other Jews. Other notable genres of nineteenth-century Jewish literature were romance literature and the so-called "ghetto tales" or "ghetto literature" of the kind popularized by writers like Leopold Kompert and Karl Emil Franzos. For scholars such as Hans Otto Horch, Jewish historical fiction was something of a failed attempt by elites (rabbis like Philippson and Lehmann) to manufacture an "ennobling" didactic literature for Jewish youth, whereas the "ghetto tales" of Kompert, Franzos and others became a successful, and indeed more "genuine" form of Jewish popular culture because it found resonance with greater numbers of Jewish and especially non-Jewish readers. In Horch's understanding, ghetto literature was "popular" to the extent that it was popular with readers or in the ways that it paralleled the kind of Volksliteratur embodied by nineteenth-century Romantics such as the Grimms, but also by Jewish writers like Berthold Auerbach, whose "village tales" (few of which had explicitly "Jewish" themes) were extremely successful with German readers. Indeed, it was Berthold Auerbach who authored both Spinoza (1837), one of the very first Jewish historical novels, as well as Schrift und Volk (1846), a programmatic work on realism as a people's literature.

But if, on one level, the village tales and ghetto stories romanticized the "old ways" and sense of community found in an idealized countryside and the historical novels celebrated and lionized princes, adventurers, and luminaries of the past, nineteenth-century Jewish literature also served as a potent means to confirm the values of its real audience: the new Jewish bourgeoisie. A "middlebrow" aesthetic appealed to Jewish writers and readers who sought to construct a modern Jewish identity that conformed to their integrationist social aspirations. In the nineteenth-century German Jewish context, a "popular" culture was first and foremost a German middle-class culture.

There was a paradox at the heart of a minority writing (and reinventing) its own history in a majority language in the era of modern nationalism. Nineteenth-century German Jewish writers wrote novels in German about Jewish history read mostly by other Jews, but their works sought out Jewish narratives that could harmonize with themes in German national culture. Thus, the abundance of Sephardic themes in the works of Heine, Auerbach, Philippson, and Lehmann can be in part explained and can acquire new meaning when we understand German Jewish philo-Sephardism in the context of works like Schiller's Don Carlos, something known to all German readers. The theme of heroic Jewish conversos resisting a villainous Inquisition was adopted by integrationist German Jewish authors in part as a bridge that could unite them with German enlighteners like Schiller. Thus, "minority culture" could also be a "popular culture," one that positions an integrating minority in relation to a majority "high culture."

Significantly, Jewish popular culture in the form of historical novels written by and for Jews in mid-nineteenth-century Germany took on a new dimension when these works were translated into Yiddish and Hebrew in the later nineteenth century. As the work of Nitsa Ben-Ari has shown, what functioned as a literature with a pronounced integrationist tendency in the German context was paradoxically transformed into a "national" literature in an eastern European context. Of course, Hebrew and Yiddish readers from the 1880s onwards consumed translations of non-Jewish European authors as well, so the question of what constituted "Jewish popular culture" in the nineteenth century stands as a matter of debate.

But perhaps the most moving testimony to the way in which nineteenth-century German Jewish historical fiction was a form of "popular" culture is the way that twentieth-century German Jewish writers returned to the genre in response to anti-Semitism in the 1920s and 1930s. Else Lasker-Schüler's strange modernist tale "The Miracle-Working Rabbi of Barcelona" (1921) seems like a fantastic and idiosyncratic story about a pogrom in a surreal, ahistorical version of Barcelona. Yet when we read Lasker-Schüler's against the background of the nineteenth-century Jewish tales by Heine and Ludwig Philippson, and we take note of Lasker-Schüler's prominent focus on childhood, we can see how Lasker-Schüler is returning to and rewriting the nineteenth-century Sephardic tales of Heine and Philippson, works she likely read as a child. Similarly, Hermann Sinsheimer, a prominent theater critic whose expulsion from German cultural life after 1933 was a tremendous blow to his self-understanding as a German Jew, responded with a novel that he published in 1934: Maria Nunnez, a Sephardic-themed historical novel that is a rewriting of an 1867 novel by Ludwig Philippson. Sinsheimer's novel was published with Philo Verlag, one of a few small Jewish publishers that the Nazis permitted to remain open until 1938: these were the only permissible publication venue for Jewish writers in Nazi Germany. Whereas in the 1800s independent Jewish publishers provided a vehicle for a new Jewish popular culture, after 1933 they were a ghettoized space where the popular literature that once was could be recollected.