All old means of communicating were once “new media.” In their novelty, they could inspire both great excitement and high anxiety about their implications for literacy, authority, authenticity, or memory (recall Socrates, in the Phaedrus, on the perils of writing). With time, the outsized expectations that sometimes accompany the advent of new media—whether verging on an Edenic transformation of the social fabric or predicting its apocalyptic unraveling—give way to their familiarity and to significant social and cultural consequences that are often unanticipated. For example, the advent of digital media, like the invention of print centuries earlier, has not only expanded access to canonical sacred texts in Jewish life but also altered how they are engaged: Orthodox women can download podcasts of Gemara shi’urim they would be forbidden to attend, would-be kabbalists run computer searches for hidden “Bible codes,” rabbis debate the halakhah on the proper handling of a damaged CD-ROM of the Talmud.

At some point, all innovative technologies yield to newer ones. Their arrival alters the use as well as the perception of the earlier media, which come to be regarded as outmoded. Sometimes, this change articulates a generational divide; think of the cohort that has been termed “digital natives” versus those of us who, apparently, bear the retronym “analog natives.” For an earlier instance, consider a feature that appeared in the Jewish Daily Forward in 1924 on whether Jewish families should buy a phonograph or a radio. The article notes that inclinations were split between immigrants—who prefer the phonograph, which enabled them to “listen to their heart’s content to Jewish tunes”—and their American-born children, whose “faculties are young and pulsating” and therefore inclined toward the radio, enabling them to “get in touch with any broadcasting station and open the floodgates of noise and merriment.” (It is also telling of an intergenerational rift in communications media that this piece appeared in the paper’s then-new English section, rather than in Yiddish.)

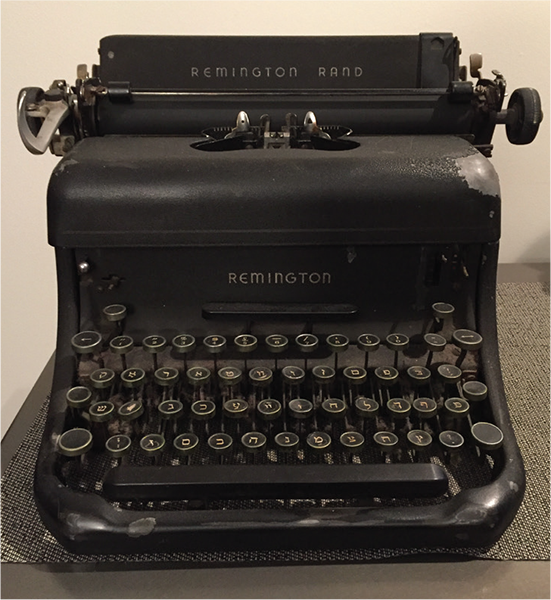

The previous two centuries witnessed an increasingly rapid cascade of new media: after the invention of the typewriter (in 1829), there are chromolithography, photography, and telegraphy (1830s); modern postal systems and the facsimile (later, fax) machine (1840s); the telephone and phonograph (1870s); hot metal typesetting, the mimeograph, and the magnetic wire recorder (1880s); silent motion pictures and wireless telegraphy (1890s); photo-offset printing and the photostat (1900s); commercial radio broadcasting, “talking” motion pictures, television, and the magnetic tape recorder (1920s); mass-market paperback books and photocopying (1930s); the transistor, the long-playing record, and the instant camera (1940s); videotape and the microchip (1950s); communications satellites, the audio cassette, holography, and the laser printer (1960s); the portable electronic book, handheld mobile phones, and the personal computer (1970s); the CD-ROM, the video camcorder, the Internet, 3-D printing, the personal digital assistant, and digital video (1980s); digital printing, the smartphone, and digital audio files (1990s). The result is an ongoing technological shift, as what was once cutting-edge becomes obsolescent—or, in the case of typewriters made by Remington, which recently went bankrupt, obsolete. What, then, becomes of all these media when they are left behind?

I thought about this when studying the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive, the subject of my book Holocaust Memory in the Digital Age: Survivors’ Stories and New Media Practices (Stanford University Press, 2017). The archive, which houses the world’s largest collection of video interviews with survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust, was initiated at the end of the last century, on the cusp of the digital turn. The archive’s tens of thousands of interviews were recorded on analog Betacam SP format videotapes, the broadcast industry standard in the mid-1990s. These tapes were subsequently digitized as part of the process of preserving, indexing, and disseminating this vast collection, which is now accessed online (a use of the Internet not yet possible when the project was initiated). This technological watershed coincides with the aging and eventual passing of Holocaust survivors. At the convergence of these two threshold moments, the newest of media is conjoined with the oldest—face-to-face conversation—each transmuting the other.

Old forms of media don’t simply disappear, even when they are put out with the trash. They can be embedded in newer technologies (the Shoah Foundation is now creating interactive holograms of Holocaust survivors with whom people can “converse”) or become vestigial, if nominally (we still “cc”—short for “carbon copy”—our emails). Or old media can leave behind the frustrating conundrum of their impenetrability, whether a clay tablet incised with Linear A or the floppy disc on which I backed up my master’s thesis in the 1980s, using a computer, long since vanished, with an antediluvian operating system.

Like our Yiddish typewriter, old media can acquire new value by dint of age. Their form becomes venerable; consider the aura of eighteenth-century documents written with a flowing hand on parchment or nineteenth-century portraits in sepiatoned cartes de visite. In the case of the sefer Torah, an antique medium can even be regarded as sacred. Old media provide added information, not simply dating works but also contextualizing the social practices of communication in which they were produced. Old Yiddish books, for example, reveal what people read some five hundred years ago as well as how they read and how new literacy practices transformed Ashkenazic life. And when we examine a digital scan of a vintage copy of a long-lost medieval manuscript, or download an MP3 of a cassette transfer of a folk song originally recorded on a wax cylinder, or scrutinize laser printouts from scratchy microfilms of newspapers, the originals of which have crumbled into brittle fragments, we are immersed in the flow of media, all once new, superseded by other technologies that will themselves soon show their age—each testifying to our ongoing efforts to record and share human creativity and insight.