Rivalry between Ishmael and Isaac in the Bible exists inasmuch as the brothers participate in the larger narrative structure of Genesis that sets one line of Abraham's descendants apart from others. The promise made to both Hagar and Abraham as to Ishmael's fate, that he will be a father of twelve nations, however, does not put him in direct conflict with Isaac, nor is there anything in the story that would lead one to believe that the brothers engaged in interpersonal conflict. To be sure, the prophecy in Gen. 16:12, "His hand will be against everyone and everyone's hand against him," portends a fate for Ishmael riddled with struggle, but not an exclusive struggle with Isaac. In fact, there is no mention of competition or warfare between them.

Furthermore, rivalry between Ishmael and Isaac is neither divinely ordained nor explicit in the narrative. On the contrary, they appear together only when they bury their father: "And Isaac and Ishmael his sons buried him in the cave of Machpelah . . ." (Gen. 25:9). The text reverses the birth order by mentioning Isaac before Ishmael. This reversal figures prominently when comparing this narrative to that of Esau and Jacob. Unlike the burial notice of Isaac (Gen. 35:29) where Esau and Jacob bury their father, in this notice the younger son is mentioned first. The reversal, "Isaac and Ishmael," portrays the brothers acting not only in unison but also in accordance with God's preordained plan whereby the younger sibling supplants the older. Although there is no active rivalry between the biblical brothers, one cannot escape the fact that the biblical narrative privileges one brother over the other. Furthermore, Jewish and Christian teachings and interpretations pit them against one another.

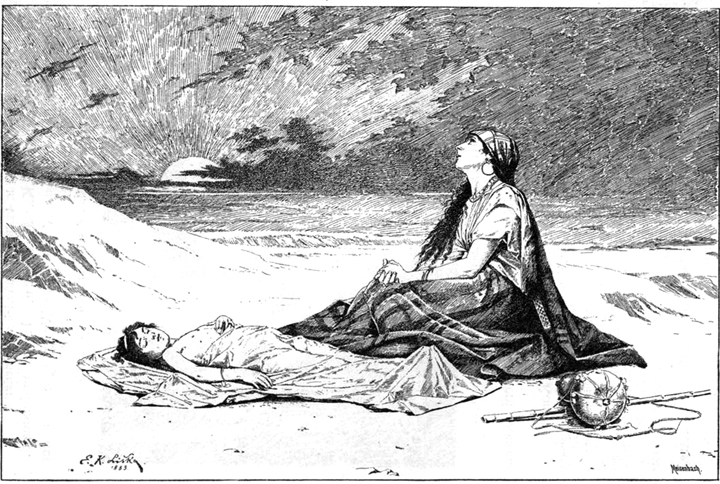

Throughout the centuries, Jewish and Christian exegetes have legitimized Sarah's demand that Abraham cast out "that Egyptian maidservant and her son (Ishmael)." The request so grieved Abraham that God had to intervene and assure him that if he acquiesced to Sarah, Ishmael would nonetheless be saved, that he would also become a nation, for he is also Abraham's seed. But if he is also Abraham's son, not only his seed but his firstborn, why did Sarah demand his expulsion? Jewish and Christian interpreters turn to Gen. 21: 9, "And Sarah saw the son of the maidservant playing [mezaheq]," for an explanation. Speculation as to what is meant by "playing" range from idol worship to fornicating, from shedding blood to abusing Isaac. Whatever the case may be, the Jewish and Christian exegetical traditions justify his biblical exclusion from the immediate Abrahamic family, the family of the covenant. For Jews, God makes a covenant with Abraham's seed through Isaac, Jacob, and their descendants. Ishmael is part of, and apart from, the family of Abraham. While it is true that he is also Abraham's son, and while it is also true that the biblical story does not portray him negatively, for most Jews and Christians he is cast in a less than favorable light.

As a means to confront the swiftly emerging political forces in the Near East and to protest against Islamic hegemony, the rabbis take swipes at Ishmael in postseventh- century midrashim. In other words, there is a greater tendency in later rabbinic compilations to malign Ishmael. One can surely understand the linkage between Islam and Ishmael in light of its initial emergence in the Hejaz, and in light of Ishmael's important role in Islam.

One of the working assumptions when using Ishmael to represent Islam is that Ishmael, not Isaac, plays a major role in Islam. To be sure, although the Qur'an does not explicitly identify Ishmael as the intended son for sacrifice, and despite the fact that some early mufassirun (Qur'an interpreters) considered Isaac the intended son, Muslims today believe that God asked Abraham to sacrifice Ishmael. Moreover, Abraham, along with Ishmael, builds the Ka'ba, the central shrine in Mecca and focus of the obligatory pilgrimage (Hajj). In the Islamic tradition Ishmael is identified as the progenitor of Arabs, and in turn with Islam.

Yet, because Ishmael is also identified with Arabs, it is misleading to employ him as an emblem of Islam, for while most Arabs are Muslims, most Muslims are not Arabs. Moreover, in the Islamic tradition both Isaac and Ishmael are considered prophets in a long line culminating with Muhammad, the seal of prophecy. In sura 2:133, Ishmael, along with Abraham and Isaac, are referred to as the "Fathers" of Jacob. Unlike in Judaism and Christianity, which marginalize Ishmael and exclude him from the convenantal family of Abraham, in Islam both are considered full members of Abraham's family.

While the sons of Abraham are understood as antipodes in Judaism and Christianity, generally speaking this is not the case in Islam. Ishmael's role within Islam is as rusul Allah, messenger of God and as nabi, prophet, as well as the progenitor of the Arab people. The Qur'an, however, envisages Ishmael's role first and foremos-t as Abraham's son, not progenitor of the Arabs. The emphasis on genealogy in Islam developed over time as Islam expanded beyond the reaches of the Arabian peninsula, and the biblical genealogy of Arabs became widely accepted. This is adduced in the charged exchange between Arabs and non-Arabs ('Ajam-i) or Persians n-in shu'ubiyyah literature, the popularity of which is questionable, that emerged in the second to eighth century as a reaction to the exclusive Arab hegemonic right in Islam. In fact, it was taken for granted by non-Arab Muslims who, in response, disparage Ishmael's birth from a slave girl, and pronounce their own descent from Isaac, born of a free woman. This tension must, however, be understood within the context of the ongoing inner-Muslim polemics that took place in the ninth century; over time these debates abated and made little impact on the prominent role of Ishmael in Islam.

And yet, utilizing Ishmael metonymically for Islam, Arabs more broadly, and Palestinians specifically, fosters a rather unsettling dichotomy between Ishmael and Isaac— the unchosen and chosen—that the Islamic tradition by and large does not support, but one upon which Jews and Christians establish their theological identity. As such, despite conciliatory efforts and good intentions, reference to the Other as Ishmael exacts a price. In many religious and academic circles the resuscitation of the figure of Ishmael has gained traction, but the accretion of negative associations and images is inordinately difficult to escape. Perhaps it is therefore best to abandon altogether the problematic paradigm that inherently sets these siblings apart, or alternatively, we can accept with forthright recognition what is at stake in calling our so-called ethnic and religious sibling Ishmael.

Carol Bakhos is associate professor of Late Antique Judaism and acting chair of the Program in the Study of Religion at UCLA. She is the author of Ishmael on the Border: Rabbinic Portrayals of

the First Arab (SUNY Press, 2006), and co-editor of The Talmud in Its Iranian Context (Brill, 2010).

Carol Bakhos is associate professor of Late Antique Judaism and acting chair of the Program in the Study of Religion at UCLA. She is the author of Ishmael on the Border: Rabbinic Portrayals of

the First Arab (SUNY Press, 2006), and co-editor of The Talmud in Its Iranian Context (Brill, 2010).