Beyond Jewish Museums

Anthropologists are inclined to see museums as social arenas as much as collections of objects. We look at the ways people interact with specially demarcated assemblages of material culture, how they treat each other in the presence of these assemblages, and the stories about ourselves, others, and the world that such assemblages enable. Culture "on display" provides the props and mise-en-scene for our ongoing performances of self.

The far end of the spectrum includes non-Jewish curations of Jewishness. This phenomenon is occurring where local populations (often, but not always, in dialogue with visiting Jews) are "re-collecting" the long-ignored, "disinherited" heritage of their former Jewish neighbors. It is taking place in Eastern Europe, in Spain and Portugal, and even in small stirrings in the Arab world. Such recollection includes a broad swath of activities that remember, revive, or (re-) create a connection with Jewishness.

Cultural theorist James Clifford has argued that collecting is a central aspect of identity construction in the Western world, a way we establish our senses of self, culture, and authenticity. We are, in essence, "collecting ourselves." What sort of selves, then, may be collectively emerging in these domains of re-inheritance that stand on the cusp between death and rebirth, forming new "contact zones" where past neighbors suddenly overlap?

Curating Difficult Knowledge

Jewish heritage in Europe, particularly Eastern Europe, constitutes "difficult knowledge." This heritage is difficult to confront not only because of the tragic wartime chapter in which Jewish material culture was looted and destroyed along with its owners, nor even because of its widespread appropriation, neglect, or blatant misuse in the postwar period. Rather, the most complex, compelling, provocative difficulty is making sense of the recent forms of embrace of Jewish heritage among non-Jews (and Jews) that has grown with the waning of communist rule.

After a half century of public censorship, Jewishness is increasingly sought out and put on display. Foreign Jews are exploring newly accessible shtetls and cities for "roots"—some yearn for tangible places to anchor family stories while others look to assert diasporic cultural affinities. But an explosion of local heritage projects reveals that non-Jews also have strong emotional claims on their murdered neighbors. The changing relationship of new generations to Jewish heritage is difficult to accept, or even to discern, in the shadow of the post-Holocaust landscape. Seeing the Nazi camps can be, perversely, more comfortable than seeing Polish teenagers dancing to klezmer music. In the face of the former, the discomfort Jews feel is at least familiar.

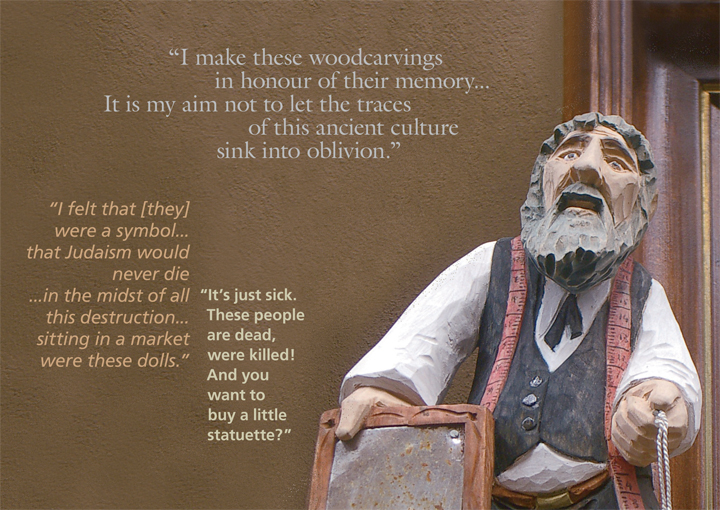

The Jewish heritage of Europe is emerging as a matter of fundamental dispute. Do former synagogues renovated into museums provide lessons on the failure of Europe and Jewish diaspora, or evidence of its richness? To whom do they belong? And what of the newly produced "Judaica" in the form of klezmer festivals, Hasidic figurines, and kosher-style restaurants, or even newly redesignated Jewish quarters, cropping up in urban centers from Girona, Bologna, and Berlin to Krakow, Vilna, and Lviv?

Jews and non-Jews may read these landscapes, objects, and spaces differently, but reactions among Jews are equally divergent. Foreign Jewish visitors tend to sacralize sites and monuments to Jewish ruin and dismiss things new or commercial as inauthentic or irrelevant at best, particularly if non-Jews had a hand in their creation. The small populations of local Jews, by contrast, may gravitate to lively spaces of Jewish folkloric expression because they attract not only other Jews, but also sympathetic non-Jews, and represent a much-needed renaissance and a claim to public identity.

Finally, the shifting demography of the new Europe along with a growing global interest in commemorating atrocity is changing the context in which Jewish heritage is understood. When Turkish schoolchildren are brought to Holocaust memorials in Berlin, what meanings do they take away?

As curators, collectors, and other heritage presenters are increasingly challenged to act less as experts and gatekeepers and more as sensitive, savvy hosts and facilitators for a broad range of visitors, what might curatorial practice look like? The field is ripe for innovation.

In my own ongoing work, I have sought to capitalize on the multiplicity that is latent in sites where Jews and non-Jews meet to contemplate Jewish history and culture. I proceed from the question of whether exhibits can serve as mirrors that do not simply reflect what Jews or others already believe about themselves or what others may believe about Jews but instead provoke a self-questioning gaze.

Here are some snap-shots of recent projects:

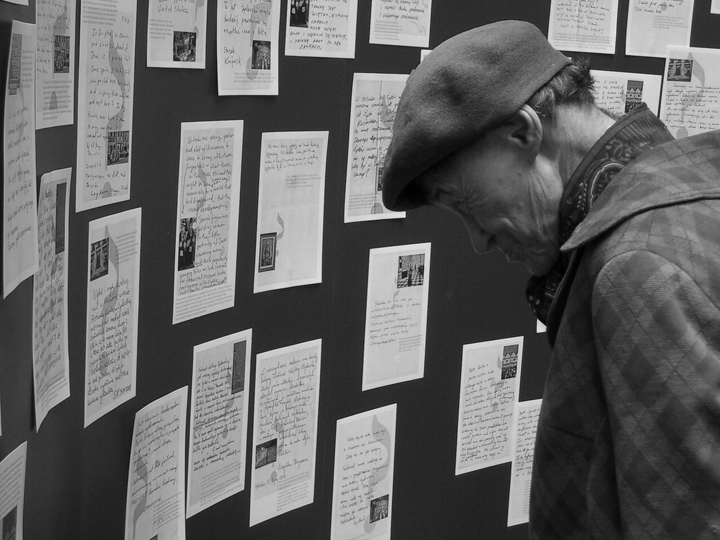

In conversationmaps (with Hannah Smotrich) the goal was to take the impassioned monologues about heritage and identity I recorded among Jewish tourists in Poland and local Poles—significant others who rarely meet—and transform them into visual dialogues. We transcribed and juxtaposed these voices with ambivalent images, and interspersed the resulting "maps" and postcards amidst more standard tourist ephemera in Krakow, hoping to catch visitors off-guard and illuminate the multiplicity of passions around popular objects and sites. Polish souvenir figurines of Jews, for example, are not so easily dismissed (or embraced) when framed by three very different perspectives on their personal meaning. Rather, they become objects of meditation on memory, empathy, and trauma.

In odpowiedz…please respond (with Smotrich and Stephanie Rowden), a quiet courtyard became a place to stop, contemplate, and converse about the celebration of Jewish heritage at Krakow's annual Jewish Cultural Festival. Run and largely attended by non-Jews, the festival elicits a range of sentiments that swirl beneath its entertaining exterior. The aim of this participatory, site-specific installation was to make these sentiments collectively, bilingually visible, enabling them to inform and challenge. Alongside celebratory proclamations, some expressed anger at "kitsch" and "appropriation," or simply voiced a sense of unfathomable loss. But a prominent Polish Jew wrote, "This place, at this moment . . . is the only place in Poland where being a Jew I feel like a host. This is a Jewish place more authentic than any other in Poland."

I am further exploring such curatorial approaches in my teaching. In a seminar, "Curating Difficult Knowledge: Engaging with the Aftermath of Violence through Public Displays, Memorials, and Sites of Conscience," I asked students to "re-curate" a video of Holocaust survivor testimony in a way that would highlight how its meaning is made, both internally (by the narrator and interviewer) and when subsequent viewers bring their own experiences and questions to it. I tried to trouble too-easy assertions of empathy and identification, and assumptions about the transmissibility of experience.

One group, picking up on the refrain that the survivor "felt safer in the forest," cut and transported tree stumps gathered from the Quebec woods for visitors to sit on as we listened to selections from the testimony. The result was the creation of a space that provoked multisensory contemplation and an intimate, social experience of listening that nevertheless highlighted our distance as witnesses.

Another group engaged visitors in a facilitated interaction with a miniature landscape, asking them to advance the story by making choices and manipulating objects. The participants were obliged at times to identify with perpetrators or bystanders rather than victims, and to reflect on how their small actions were caught up in much larger, ambivalent processes. The participatory curation also evoked questions of what memory becomes in our hands, behind glass, under our control. One student's choice to move a wooden dreidl "back in time" from the ghetto into an intact, prewar Jewish neighborhood was a surprisingly moving gesture. As the student later reflected, this effort to reverse the hellish historical process and restore the ritual object to a time of more "wholeness" perhaps also honored the survivor's wish, expressed in her testimony, that Jewish tradition continue to be remembered and enacted. Such experiments suggest new ways that activation of the past might enliven the present.

I continue to expand on these projects and am encouraging others to do related work in a new research center CEREV (Centre for Ethnographic Research and Exhibition in the Aftermath of Violence) we are constructing at Concordia University. A key component of the center is a digital "exhibition lab" for which I have planned a program of "research curation," exploring how humanistic scholarship and qualitative data on social experience can be mined, reframed, and re-circulated via unconventional pathways to educate and to stimulate difficult, important conversations about histories of violence.

With these resources, I hope to open spaces for new scholarly and public understandings of the aftermath of mass violence. Both ethnography and curatorial practice can be productively reconsidered in light of the particular risks and challenges of such "difficult knowledge." Project-based, interdisciplinary collaboration across the arts, humanities, social science, and new media offers new possibilities for innovative, productive curation of the cultural legacies of social suffering.

Erica Lehrer is a socio‑cultural anthropologist and curator. She is currently Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in the Departments of History and Sociology‑Anthropology at Concordia University, Montreal. She is the author of Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places (2013), and co‑editor, with Michael Meng of Jewish Space in Contemporary Poland (forthcoming), and of Curating Difficult Knowledge: Violent Pasts in Public Places (2010).

Erica Lehrer is a socio‑cultural anthropologist and curator. She is currently Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in the Departments of History and Sociology‑Anthropology at Concordia University, Montreal. She is the author of Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places (2013), and co‑editor, with Michael Meng of Jewish Space in Contemporary Poland (forthcoming), and of Curating Difficult Knowledge: Violent Pasts in Public Places (2010).