Briefe by Yosef Trumpeldor (1925).

The process of removing the Land from the religious sphere and transplanting it to the national sphere occurred slowly, and was embraced only by Zionist adherents. Most Orthodox Jews viewed this process as an attempt to force the issue, a blasphemy, and objected fiercely to it. The adoption of religious terms such as redemption and the Return of Zion, and the use of the Hebrew language in non- religious functions were all rejected and savagely criticized by Orthodox circles.

It was through this process that the Holy Land became "our land," and soon it would be called "homeland," moledet in Hebrew. This was the modern Hebrew adoption of a biblical term that had signified one's place of birth: "Go forth from your land and your birthplace [moladetkha], and your father's home, to the land I will show you" (Genesis12:1, Robert Alter's translation). The new meaning was taken from the Russian rodina which means the country of one's birth. Zionists who came from Russia used terms they had learned back home. Hence, the Hebrew translation of the standard Russian term for "Jew," yevrei, was translated into Hebrew as 'ivri, and was used profusely, supplying endless opportunities for scholars to dwell on the so-called Zionist attempt to disengage from the Diaspora by using the term 'ivri instead of yehudi. In fact, however, both terms were used interchangeably, and only later scholars read deep meaning into it. Moledet was interchangeable with "our 'erez . ," and both were Zionist secular terms for the land. The popular songs reflected the growing tendency of the youngsters growing up in Palestine to call it moledet, the country of their birth: "Let's build our land, our homeland"; "We love you, homeland." The image of the land as mother also appeared—"We sing to you, homeland and mother." During the 1937 controversy about partition, one youngster wrote: "one cannot carve up the body of a mother."

The fervor for the land had hardly anything to do with its holy sites. The four holy cities (Old Jerusalem, Zefat, Tiberias, Hebron) did not attract the pioneers in particular or immigrants in general. The fast growth of Tel Aviv reflected the trend to avoid the historical holy places in favor of the modern city, and the settlement in the Jezreel Valley and along the River Jordan created the modern holy sites of pioneering Palestine.

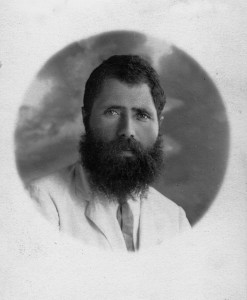

The generation of the immigrants yearned for the Land, were ready to devote their lives to backbreaking work in order to settle it, but their love was somewhat detached from the geography of the country. It was the native-born sons and daughters who covered the country on foot. But they too avoided the holy sites: The Tomb of the Patriarchs, the Wailing Wall, and even the Tomb of Rachel were not considered attractive destinations for young people's hikes. They went on trips to the Tombs of the Maccabees, to Masada, sites that symbolize Jewish heroism, and which had no importance in century-old Jewish traditions. New sites of pilgrimage appeared, for instance the tomb of Trumpeldor in Tel Hai, with the statue of the roaring lion, which was a site of veneration for youth movements on both the left and the right.

Jewish settlement went to areas where there were tracts of land for sale and which were sparsely populated by Arabs. These were mostly along the Mediterranean, and in the valleys and Upper Galilee. As a result, the historic homeland of the First Temple, the places where the epos of the emerging people took place, were actually outside of the boundaries of Jewish settlement and eventually outside of the borders of the state of Israel during its first nineteen years. Apart from the extreme right, no one was disturbed by this. When Geula Cohen, a right-wing activist, interviewed Ben-Gurion on the eve of Israel's nineteenth anniversary and asked him whether he would teach his grandson to yearn for East Jerusalem, he replied: If he likes—he can yearn, I won't tell him to. The state was busy with the economy, the army, and immigration, and was considered big enough to accommodate the needs of the Jews who wished to immigrate to it. It was only after the Six-Day War that the country was suddenly swept by messianic fervor. The land of the patriarchs, the cradle of the Jewish nation, the Temple Mount, spoke to many, out of historical and national sentiments. A small core of religious zealots assigned a divine meaning to the events. While the general public lost its taste for the Occupied Territories soon after the Yom Kippur War, the religious core slowly became the leading element in settling the West Bank. After the 1977 change of government and the rise of the right, they received government support, which leads us to the present-day predicament.

The reappropriation of the Land by the religious took place under the combined banner of religion and nationalism, using all the symbols of secular Zionism but loading them with a new religiosity that was absent from the original. In a way, this is reminiscent of the Islamic notion of combining temporal rule and religious zealotry. It is time to go back to Ben-Gurion, who insisted that borders were always the result of exigency, that the history of Jewish sovereignty did not sanctify specific areas of the Land, and that we should act according to state wisdom and leave religious considerations to the coming of the Messiah.