As we know far too well from recent events, natural disasters lay bare latent social tensions and can lead to violence and scapegoating. Catastrophes, such as the plague, could lead to anti-Jewish sentiment and violence. Of course, persecution of Jews depended on numerous and often localized variables. Consider the expulsions of Jews during the Black Death in the middle of the fourteenth century. In many cases, as the German historian Alfred Haverkamp has demonstrated, the actions against Jews may have been precipitated by news of spreading disease, but the actual expulsions of or attacks against Jews often occurred in advance of the plague reaching a particular town. Indeed, many such actions against Jews were premeditated and coincided with the Jewish or Christian Sabbath or Christian holidays, occurred during periods of increased religious tension or sentiment, and were instigated to address broader economic or political concerns. At the same time the sources describing natural disasters indicate the opportunity for constructive engagement and cooperation between people of different religious faiths and social backgrounds, even when such positive interaction did not fundamentally alter extant social structures in the long run.

The topic of responses to natural disasters encourages the analysis of a wide range of sources—Jewish and Christian— including chronicles, memoirs, memory books, civic legislation, sermons, biblical commentaries, scientific treatises, and illustrations. It also allows for the integration of diverse scholarly methodologies, including most notably the work of environmental history. In fact, Jewish Studies and environmental history share a number of characteristics that make them intriguing to consider in tandem. They both developed in significant ways in the 1960s in response to unprecedented social, religious, and political conditions. They have both been shaped and informed by interdisciplinary research, especially that which grapples with modernization theories and postmodern concerns. They have both encouraged broad comparative histories and have lavished increased attention on marginalized groups.

For both early modern Jews and Christians natural disasters were often seen as divine punishment for human sin. This could lead to calls for stricter religious observance and penitence. But this "economy of sin" might also provide the opportunity for confessional polemics. While Jews were rarely blamed directly for natural disasters— Jews did not wield such power—they could be seen as catalysts for suffering, for example through allegations of hoarding of goods and resources at times of dearth. On the other hand, Jewish writers themselves might use narratives of natural disasters to critique Christian society and they often made note when large numbers of Christians, as opposed to small numbers of Jews, were killed by floods or earthquakes, suggesting God's punishment for Christian guilt and a higher moral standard for the Jews.

On a fundamental level, natural disasters impacted access to and prices of food and resources. As the seventeenthcentury Alsatian Jewish writer Asher Levy of Reichshofen noted in his memoirs, God controlled the weather, and the effects on agriculture could be significant. For the summer of 1626, for example, Asher wrote that it was extremely rainy and damp, with the sun appearing only a few days. He noted that it was a time of emergency, but that in the end God was merciful. After detailing the extensive crop of fruit and the price of grain, Asher narrated a fall in price, concluding that ". . . we hope that it will become still cheaper, if it is the will of God."

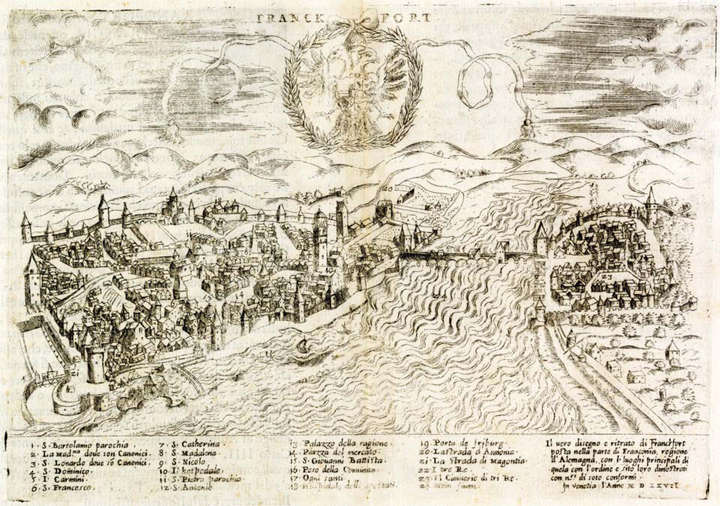

Or consider the flood narrative appended to the community customs book of Juspa, the Shammash of Worms, which detailed a series of floods in the middle of the seventeenth century. At times, Juspa focused on the impact of flooding on the Jewish community specifically, noting the damage done to houses and wine cellars. However, Juspa also described the effects on the broader population and he frequently extended his comments beyond the borders of the Jewish quarter. (Similar balancing characterized the many Jewish accounts of the great flooding of the Rhine in 1784, for which we have a good deal of information from Christian as well as Jewish sources.) In his account of various floods, Juspa detailed the obstacles to travel, death of animals, destruction of grains and vines, as well as man-made edifices such as wooden bridges, mills, and houses. Juspa noted that the confluence of multiple floods in one year was a great and powerful miracle for everyone to see and hear, and he pleaded that the mighty waters not bring any further trouble. Like other early modern German chroniclers, Juspa recorded local events to serve almost as an archive of local history, and his account clearly made Jewish experiences part and parcel of broader local and regional historical events.

The more detailed flood narratives of the later eighteenth century provide examples of cooperation between Jews and Christians—in rescue operations that involved people in boats pulling survivors from rooftops, as well as in the distribution of foodstuffs and the provision of temporary housing to Jews and Christians forced to flee the rising waters. As one Christian eyewitness in 1784 recalled, "Here sit together Christians and Jews, Roman Catholics and Protestants, oppressed by the same dread, filled by a purpose and they pray in brotherhood to one God to save and spare them." The same writer, of course, concluded that, "Only a few give a lasting impression of a true improvement of life. Only a few pay the Lord their vows by discarding what displeases Him."

Narratives of natural disaster also reveal essential differences between Jews and Christians, pointing out, for example, the foreign-sounding nature of Hebrew prayers and the necessity in some cases for squads of police to be stationed to protect Jewish quarters from being looted. Indeed, even when not blamed for calamities such as epidemics, Jewish security and legal standing appeared rather tenuous in some early modern catastrophe narratives, such as an episode of the plague detailed by Asher Levy of Reichshofen in the early seventeenth century, when local Jewish houses were vandalized. Still, many early modern Jewish accounts make no mention of negative consequences for the Jews; they often portray episodes of assistance between Jews and Christians; and they suggest that Jews and Christians were familiar with their neighbors and their neighbors' religious practices. Some early modern Jewish accounts even allow us to peer into daily interactions between Jews and Christians and they provide hard-to-come-by details about internal Jewish life—social tensions, communal organization, and settlement patterns in various German cities, towns, and villages.

Drawing from diverse sources and a broad range of methodologies (including exciting work in integrated history, emotion history, the study of daily life and local knowledge, as well as environmental history), the experiences of Jewish life on the land and the responses of Jews to natural disasters will complicate the standard metanarratives of Jewish history. Jews were in many ways simultaneously separate from and integrated into the larger early modern societies in which they lived. Discussions of crisis and natural disaster hold the opportunity to challenge (and confirm) traditional historical sensibilities as well as to unearth many aspects of Jewish life and Jewish- Christian interactions that can provide a more nuanced picture of the Jewish past.

Dean Phillip Bell is dean, chief academic officer, and professor of Jewish History at the Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership. He is the editor of The Bloomsbury Companion to Jewish Studies (London, 2013).

Dean Phillip Bell is dean, chief academic officer, and professor of Jewish History at the Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership. He is the editor of The Bloomsbury Companion to Jewish Studies (London, 2013).