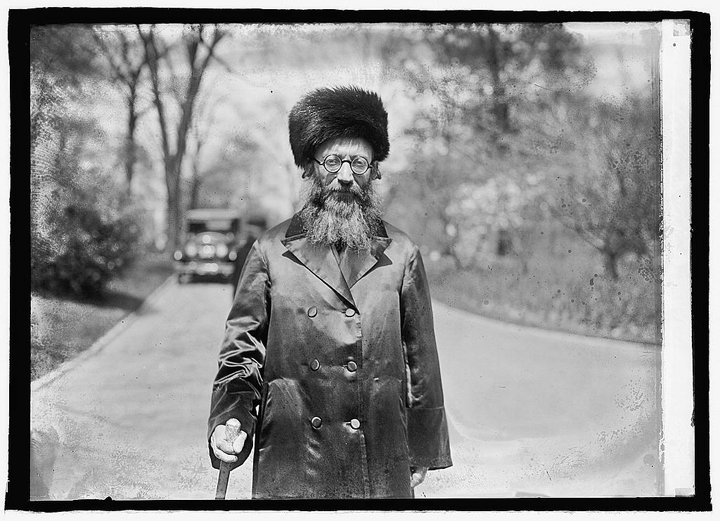

April 15, 1924. Library of Congress.

'Erez Yisra'el is no extraneous thing, an extrinsic property of the nation, some means toward general unity and the maintenance of its physical or even spiritual existence. 'Erez Yisra'el is a thing in itself, bound in a living tie with the nation, embracing its very existence by its unique internal grace. And so, one cannot grasp the substance of the unique sanctity of 'Erez Yisra'el, nor actualize its depth of affection—only by the divine spirit that is upon the nation as a whole, in the natural spiritual impress that is in the soul of Israel.

Rarely has a bit of theological reflection—in a spiritual diary no less—had such concrete and far-reaching political effects in modern times as these lines, written in late 1915 by Rabbi Avraham Yizhak Ha-Cohen Kook, in his wartime exile in Switzerland. In July 1914, after an intense decade in Palestine as chief rabbi of Jaffa and the surrounding colonies (in other words, of the New Yishuv) he and his wife Rivka had traveled to Europe, he to speak at an Agudat Yisra'el conference (hoping to at least ameliorate some of organized ultra-Orthdoxy's implacable hostility to secular Zionism), and she for medical treatments and to take the waters. The outbreak of war caught them by surprise, in Germany, where they narrowly escaped interment as foreign (Russian) enemy nationals and found refuge in Switzerland. This forced isolation gave Rav Kook time to write and reflect, including on just how electrifying his encounter with the Land of Israel had been. Interestingly, in his many writings predating his Aliyah in 1904, the Land of Israel scarcely figures, certainly not as a category of theological analysis and lens through which to view other concepts and contemporary movements (this, in contrast to the Jewish people who so figured for him from the beginning). This changed with his migration; not only did halakhic questions arising from settling the land begin to take up his attention— most famously in his controversial support for the sale of the land to non-Jews during the shemittah year, in order to preserve and support the burgeoning enterprise of agricultural settlement, but in his theology as well. This meant not simply reckoning with the theological import of the Land, but weaving it into his emergent vision of secular Zionism's paradoxical role in the long-awaited redemption, not only of the Jewish people, but of Judaism itself and the natural world. Thus, writing in his spiritual diary circa 1913, he says: The holiness within nature is the holiness of the Land of Israel, and Shekhinah that went down into exile with Israel (after BT Megillah 29a) is the ability to preserve holiness in opposition to nature. But the holiness that combats nature is not complete holiness, it must be absorbed in its higher essence to the higher holiness, which is the holiness in nature itself, which is the foundation of the restoration and repair of the world entire (tikkun olam) and its utter fragrancing. And the holiness in exile will be joined to the holiness of the land, and the synagogues and batei midrash of Bavel will be reestablished in the Land of Israel (citing BT, ibid.) Elsewhere he writes that the unique quality of the Land of Israel is "the sanctification of every mundane thing in the world."

Rav Kook here was reinterpreting a rich skein of kabbalistic thought, in which the divine presence, the Shekhinah, as the Oral Torah, is Knesset Yisra'el, the sacred community of Israel, and thus the Land, are all ultimately as one, constituting, as Sefirat Malkhut, the very meeting point of God and the world, and themselves the stuff of revelation. As Yosef Gikatilla writes in his thirteenth-century classic, Sha'arei 'Orah Know that the first Name which is closest to all creatures and through it they enter into the presence of the Blessed King, and there is no other way in the world to see the face of the Blessed King other than by this Name is the Name called "Adonai" . . . and sometimes this dimension is called "Shekhinah" [Indwelling/Presence] . . . and . . . "Malkhut" . . . Always reflect on how this dimension is always known as "Torah she-be-'al Peh" . . . And . . . in every place that you find the Rabbis of blessed memory referring to "Knesset Yisra'el" [the ecclesia/gathering of Israel] it is this dimension called "Adonai" and called "Shekhinah" . . . and in this manner she is called "'Erez Yisra'el" [the Land of Israel] . . . In this densely allusive network of ideas, Israel's exile from the land was part of the alienation of the eternal, unchanging written law from the vibrant, responsive oral law. These alienations—of people, land, and Torah—all in turn reflect the divine presence's fundamental homelessness in the world—to be cured, in Rav Kook's audacious dialectical vision, by none other than the revolutionary dislocations of secular modernity. Rav Kook was far from the only supporter of Zionism talking about redemption. Shmuel Almog has shown that as far back as 1876, the soon-to-be founders of Petah Tikvah characterized the purposes of their newly founded enterprise as "working the soil and redeeming the land." Those religious settlers were certainly aware of the biblical use of "redemption" as the restoration of land to its rightful heirs, as were later activists like Yehi'el Mikha'el Pines and Eliezer Ben-Yehudah. The same can be said for more radical thinkers and pioneers like Aharon David Gordon. "What have we come to do in 'Erez Yisra'el?" he wrote a correspondent in 1912: "To redeem the land . . . and resurrect the people. But these are not distinct tasks, but two sides of the same one." In 1918, Berl Katznelson wrote that the Jewish National Fund was nothing less than "the revelation of the Shekhinah of the nation." Henry Near has argued for a subtle but important shift in Labor Zionist language in the interwar period from "redemption" to a different, more prosaic, biblical terms, haluziyut. (Both Almog and Near's studies are in Ruth Kark ed., Ge'ulat Ha-karak'a be-'Erez Yisra'el [Jerusalem: Yad Ben Zvi, 1990]). Boaz Neumann, in his extraordinary book Land and Desire in Early Zionism (Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2011), has shown the incredible erotic pathos with which those haluzim infused their encounter with the land. The residual sacred meanings met with a new ethos of self-expression and fulfillment fusing the individual and national subject—a fusion that Rav Kook, on the other side of the tracks, saw as a step towards the paradoxical fulfillment of God's own longing Labor Zionists, for their part, by draining the traditional religious terms of their transcendent reference, were able to harness the rhetorical and spiritual power of religious language to their enterprise, and in so doing to argue—often persuasively—that while it was in many ways breaking with Judaism, it was in other ways powerfully reinterpreting it and thus laying a claim to be both the tradition's opponent, in the name of national liberation, and its rightful heir. That use of religious language rested on the traditional backgrounds of the Labor Zionists, and on religious traditionalists having abandoned the field of large scale political programs, leaving Labor Zionism to remake and set the terms of the new language of Zionist politics. But neither of those conditions lasted for long. Labor Zionists, precisely because of their revolutionary commitments, educated their children out of engagement with traditional Jewish sources. At the same time, Religious Zionists eventually came to see themselves as capable of pursuing large-scale programs within the framework of Zionist politics, thanks not least to the conceptual tools provided them by Rabbi Kook. Moreover, the passages from his journals cited earlier, and many others like them were edited, published and effectively canonized by his son Rav Zvi Yehudah, in volumes like 'Orot. After the Holocaust Zvi Yehudah came to conclude that the only possible divine reason for that slaughter was the sheer imperative of redeeming 'Erez Yisra'el.

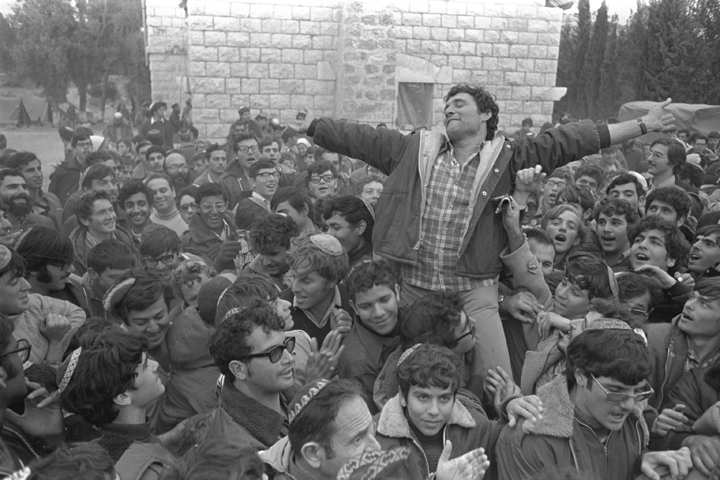

And so when in the 1970s and the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War of October 1973 Religious Zionists decided to capture the flag and lay hold, not only of the hilltop of Judea and Samaria but of the Zionist movement as a whole, they were taking th religious language that Labor Zionism had made into a functional tool for a political program and reinfusing it with its classical religious meaning. "Redemption of the land" would now mean land purchases, or seizures, and prosaic acts of settlement building under the auspices of the secular Israeli state (and those prosaic purchases, and building efforts) would themselves be the messianic redemption dreamed of for generations. Not only were they re-enchanting the enterprise—but precisely because of the phase of disenchantment, thw re-enchantment now had special power, the recharging of the language part of an electrical recharging of the Zionist project and indeed of all human history. Heaven and earth would be reunited, with heaven having come into new power, precisely for its overcoming the earlier divorce.

While the State of Israel has pursued its settlement policies for a variety of reasons and in an odd mix of assertiveness and uncertainty, the settler movement inspired by Zvi Yehudah's interpretation of his father's teaching has stood at the vanguard, pushing ahead through thick and thin (its resolve only hardened by Palestinian rejectionism and terror). To be sure, there have been other interpretations of Rav Kook from within the Religious Zionist camp, most notably that of my own teacher, Rav Yehudah Amital, who argued, contra Zvi Yehudah, that the Jewish people and the Torah properly precede 'Erez Yisra'el in a religious scale of values, and that it is Rav Kook's ethical teachings which are to provide the hermeneutic key to the his vast corpus of teachings. But that has been a decidedly minority view. In the present, commitment to continued Jewish peoplehood as an embodied people, the majority of which currently lives on the soil of the historic Land of Israel, necessarily entails a serious reckoning of the meaning of that embodimen and that landedness. Those of us who do not share the settlement movement's politics are challenged to develop a dis/re-enchantment of our own, one which understands the salience and necessity of embodiment and the charismatic power of the Land while constraining the ethical deformations towards which it can lead us when uncoupled with concern for flesh and blood people, and the imperatives of moral law. In a letter from 1918, Gordon wrote that only in the Land of Israel do the Jewish people come to feel the true pain of their existence, and hence begin to heal. Since he wrote those lines Jews were made to feel far worse pains in the lands of their exile. One can only hope that we will have the wisdom to use the memory of those pains, and the pains of the Land, to goad us into the work of healing.