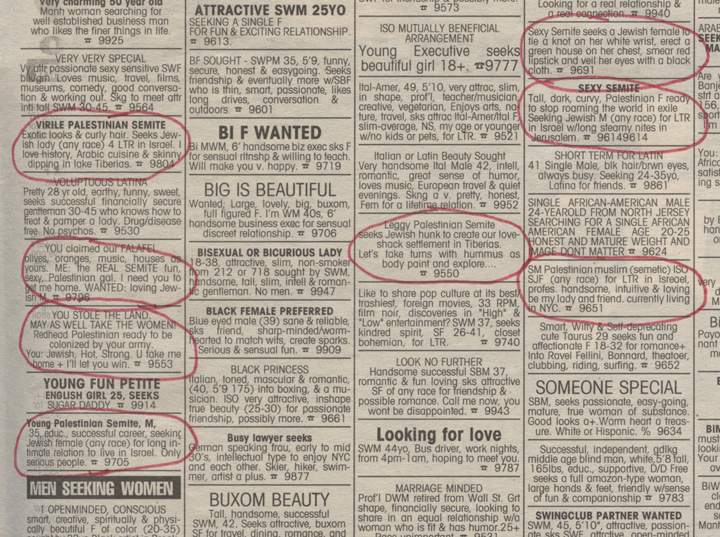

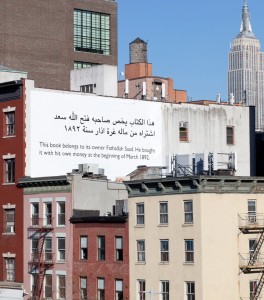

I've written elsewhere about the diasporic map as a ragged palimpsest, with multiple, enduring centers that mark the experience of diasporic movement and community. Jacir's work is an important instantiation. Her video juxtaposition of Palestinian hair salons, travel offices, and grocery stores in Ramallah/New York (2004) or stazione (2009), an installation of Arabic names for the vaporetto stops on Venice's Grand Canal are relatively benign—though stirring—acts of comparison or intrusion. I think about these markers as I read the tram stops in my own multicultural Toronto neighborhood. Such gestures reinforce the porosity of diasporic boundaries, as distinctive cultures meet in mutual recognition. More often, however, Jacir's perspective is trenchantly exilic, focused on locations where uprootedness, closed borders, and never-at-home-ness shape consciousness and daily life. At the same time, her subjects are never exoticized, nor do they provoke an anthropological or pitying gaze. Without softening the injustice of the conditions they represent, their appeal is empathic and at times even humorous. How can one not be amused by personal ads in New York's Village Voice—again a diasporic setting—posted by a Palestinian SEXY SEMITE (2000-02) seeking an Israeli partner?

Jacir came to international attention with the Memorial to 418 Disappeared Palestinian Villages Destroyed, Depopulated and Occupied by Israel in 1948 (2001): a simple canvas refugee tent was embroidered with the names of destroyed Arab villages. (The subject of disappeared Arab villages also appears in work by Israeli artists Micha Ullmann, Joshua Neustein, and photographer Miki Kratsman. Ein Hod, the well-known Israeli artists' village founded in 1953, replaced the Arab village of Ein Hawd.) As a symbol of displacement and not-home, Jacir's community-based art project was provocative and poignant, but like many monuments in museological space, it seemed disconcertingly untouched and pristine.

installation. Dimensions variable. Photos courtesy of the artist. © Emily Jacir, Courtesy Alexander and

Bonin, New York.

installation. Dimensions variable. Photos courtesy of the artist. © Emily Jacir, Courtesy Alexander and

Bonin, New York.

In contrast to this kind of gallery presentation, Jacir's more performative works in film and video take viewers on shared journeys of discovery that are ridden with obstacles. The video Crossing Surda (a record of going to and from work) (2002) documents the artist's travel to her teaching position at Birzeit University near Ramallah, an experience shared with other Palestinian workers crossing through an Israeli checkpoint. Filmed covertly through a hole in her bag, the images show obedient fellow walkers and armed Israeli guards. The land seems peculiarly no-place-- a barren roadway barely punctuated by a distant apartment block or electrical tower. But the fortuitous framing, tilted perspectives, and lurching rhythm also record the clandestine haste and danger.

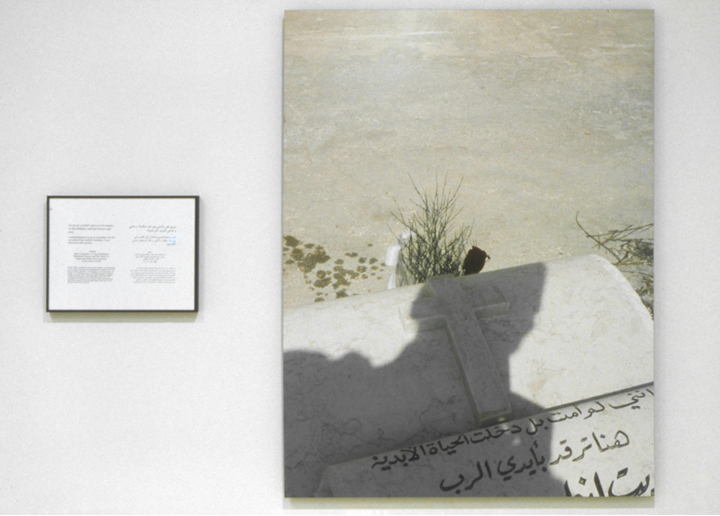

Such restriction heightens the criticality of her art. In a visit to Israel, Jacir did manage to produce Where We Come From, (2002), a series of partnered image-text panels recording the artist's invitation to Palestinians-in-exile suggesting a task that she will complete in their stead. "Go to my mother's grave in Jerusalem on her birthday and put flowers there and pray," (Munir); "Go on a date with a Palestinian girl from East Jerusalem that I have only spoken to on the phone," (Rami); "Go to Haifa and play soccer with the first Palestinian boy you see on the street," (Hana). The text appears in short English and Arabic paragraphs, with different fonts for the requesting voice and identifying data:

-Munir

Born in Jerusalem. Living in Bethlehem.

Palestinian Passport and West Bank I.D.

Father and Mother from Jerusalem.

(Both exiled in 1948.)

1 video. Photo: Bill Orcutt. © Emily Jacir, Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York.

When I visited Palestine, I heard the cabbies call as I moved with a friend through the Jerusalem-Bethlehem checkpoint, my Canadian passport unexamined and unmarked. I travelled with Jacir's work in my thoughts, mindful of my distance from her—or any Palestinian's—experience. I was certainly a stranger, but not quite a gawking tourist, and I struggled to find a meaningful way to be. What, in this troubled place, did I expect to see?

For this diasporic Jewish visitor, Emily Jacir's art speaks to and complicates my dilemma. Charged as it is, the work seems to push past indignation, substituting a shared sense of loss. I am left with no easy answers and my own view seems simultaneously fractured and multiple. Looking at her work, the perspectives shift, the events widen, and so does history.