The best honey, found in aisle three on the left, came from the Jewish Autonomous Region, often abbreviated as the JAR and less often known as a land flowing with milk and honey. I tasted every product the beekeeper from the regional farm of Valdheim offered up, purchased small jars of JAR honey to bring home as gifts, became dizzy from the sugar rush, and decided I had eaten enough.

Beekeepers have been making Russia's best honey in the JAR since its establishment. Explored in the 1920s and formally named a political entity of the Soviet Union in 1934, the Jewish Autonomous Region, often called Birobidzhan for the two rivers that run through the area, was Communism's answer to divinely ordained Jewish rootlessness. Jewish religious tradition asserts a messianic age in which Jews, both dead and alive, would be returned to the Holy Land. Soviet Jewish ideologues, not unlike their Zionist counterparts, proposed a secular eschatology in which Jews' historic exceptionalism would be overcome by settling on and developing a land "flowing with milk and honey" (Exodus 33:3). What Exodus didn't mention was that although milk and honey are naturally occurring animal products, to make the land flow with them would require a bit of human intervention.

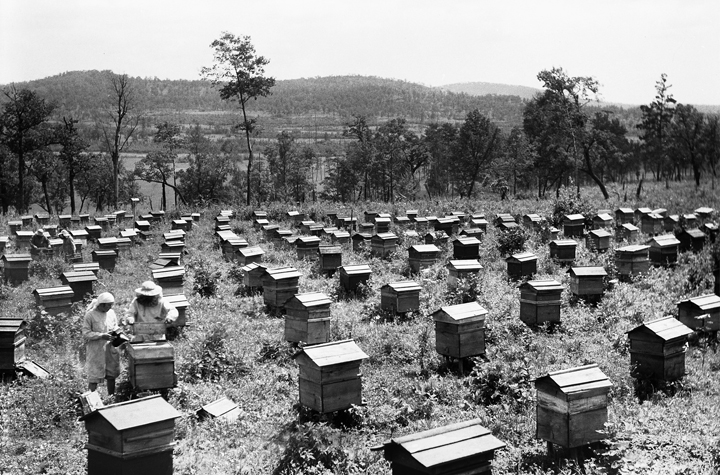

Media campaigns trumpeted the opportunities that awaited the Jewish migrant, who braved the days-long (well, often weekslong) trip from Moscow to Tikhonkaya, later known as Birobidzhan, to build the Jews' land. A migrant would arrive to find a fantastical wonderland of happy children frolicking in the outdoors, Jewish farmers communing with nature, beekeepers and their apiaries, and strapping men and women building new cities. The foreign media was no less excited about the messianic possibilities. Socialist Jews and even some non-Jews around the world raised money to develop the JAR, a campaign that included significant donations from important non-Jewish American politicians, convinced, during the Depression, that this was a project worthy of support.

Photographers, nearly all of whom were Jewish, traveled there to make arresting photographs that would captivate readers on the homefront and abroad with pictures documenting how Jews were turning the taiga into a land literally flowing with milk and honey. In 1936-1937, at the peak of messianic fervor surrounding the JAR, publications from Moscow to New York referred to the JAR as the Jews' national home with Yiddish, not Hebrew, as its national language.

So if the JAR was a false Zion, like so many that preceded it, why does it still exist on a contemporary map of Russia? What was this beekeeper doing at the Honey Bazaar proudly representing the JAR? Her last name did not suggest she was Jewish, and yet, she was proudly representing the Jewish Autonomous Region.

Some of Zvi's followers, a group of people called the Dönmeh, created new forms of collective identity that blurred the boundaries between Jew and Muslim. Perhaps the so-called failure of Birobidzhan to "solve" the Jewish problem by rooting Jews in an imaginary political fantasy created, like Zvi's failed messianism, something radically new.

While it did not create a homeland for Jews, it fostered a Jewish national cosmopolitanism. To be sure, there are Jews in the JAR today led by fearless Chabad rabbis, who follow the spark of Jewishness wherever it may be found. Their presence in Birobidzhan, however, is no different than in Krasnoyarsk, Russia, or Cheyenne, Wyoming. This radical experiment in Jewish nationalism, the JAR became a place where in the 1930s, Korean rice farmers learned Yiddish to communicate with regional administrators and Russian Cossacks married the few Jews who moved there. Today, the JAR is the only place in the world where Chinese businessmen pull into the region's main train station and are greeted with enormous modernist Yiddish letters trumpeting their arrival in BIROBIDZHAN and a Russian beekeeper could proudly tell me that honey from the Jewish Autonomous Region, well at least her honey, was the best in all of Russia.

David Shneer is the Louis P. Singer Chair in Jewish History at the University of Colorado Boulder and author of the awardwinning Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War, and the Holocaust (Rutgers University Press, 2010).

David Shneer is the Louis P. Singer Chair in Jewish History at the University of Colorado Boulder and author of the awardwinning Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War, and the Holocaust (Rutgers University Press, 2010).