The debate about Jewish productivity and labor predates the Zionist movement, which imagined the new Jew redeeming himself through the labor of his hands. When it came to discussions of how to integrate the Jews into European society, maskilim across late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe advised that Jews become models of productivity. They counseled Jews to abandon their narrow range of economic pursuits and instead to enter fields beneficial to society; this occupational turn would also benefit Jews as a group and reflect well on Jewish participation in the commonweal.

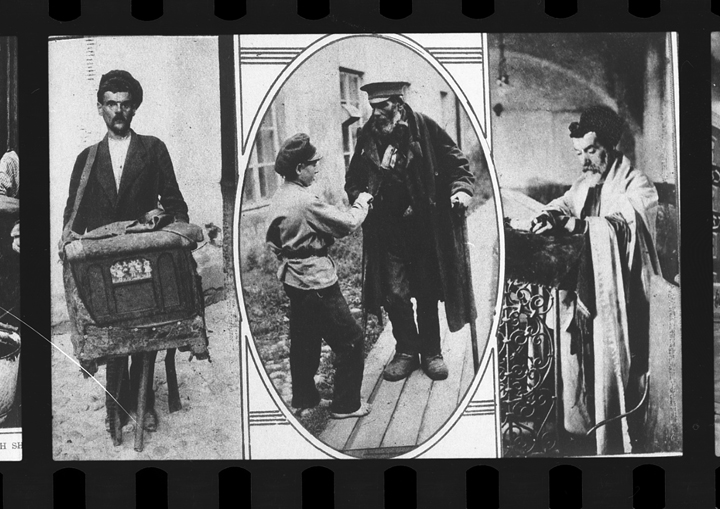

In making these recommendations, Jewish reformers were reacting to widespread Christian perceptions of Jewish economic parasitism and criminality (in western Europe) and exploitation (in eastern Europe). But by the mid-nineteenth century, the Betteljuden, highway robbers, horse thieves, and other scoundrels and undesirables who tended to predominate in the Christian imagination had, for a variety of reasons, disappeared from much of Europe. Much to the dismay of Jewish reformers, however, the Russian Empire still had its fair share of Jewish loafers, vagrants, and professional beggars. Yiddish terms attest to the many names for various kinds of beggars: schnorrer, betler, shleper, kabtsn.

Archival documents reveal that, under the draft system instituted by Nicholas I in 1827, Jewish communities presented those who did not contribute to society for conscription. One document speaks of “idlers [the writers surely had the Yiddish term batlonim in mind, though the language used was Russian], those not paying taxes, and similar undesirables.” The first ethnographic studies of the Jews of the Russian Empire (one written by a Christian, the other by a Jew) agreed that the members of the Jewish underclass preferred begging to honest hard labor, and that Jewish charitable giving encouraged this trend. These vagrants were described as rude and audacious, roaming the Pale of Settlement in large groups and lodging in the hekdesh, the combination poorhouse, sickhouse, and wayfarers’ hostel found in most shtetls.

![Hekdesh [poorhouse]. P166 dalet 16 Annopol bogadelnia, The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People.](http://perspectives.ajsnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/hekdesh-P166-dalet-16-Annopol-bogadelnia.jpg)

The didactic goals of Yiddish writers such as Ayzik Meyer Dik and Mendele Moykher Sforim (S. Y. Abramovitsh) led them to write expansively about the Jewish underclass and to expand the definition of the schnorrer to include anyone who made a living off of Torah study or the commandment to give charity. The insinuation that students of Torah exploit honest folk is nothing new, but its roots may lie as much in fiction as in fact.

In the early 1860s, a group of Jewish progressives in Odessa, which included the city’s state-appointed rabbi Shimon Aryeh Schwabacher, submitted a proposal to the authorities for a set of western-style, “scientific” philanthropic institutions, comprising a hospital, an old age home, an orphanage, and a vocational school. The proposal called for the hospital to have a hospice of sorts (bogadel’nia) to house people with incurable illnesses, those unable to work, and people whose physical defects or deformities aroused disgust in others and were thus presumably unable to lead normal productive lives. Notably, the proposed institution was to accept only local residents (i.e., no vagrants) who were also “truly [or absolutely] poor” (sovershenno bednye). Its inmates were to be made available to other institutions for miscellaneous chores. This is a fascinating amalgam of the traditional hekdesh—home to all those on the margins of society: the sick, the destitute, even the ugly—and the kind of rational philanthropy that had been accepted for some time in western and central Europe that dictated that the deserving poor had to be truly destitute, local, and willing to work.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Jewish social scientists began to argue that the putative “army of beggars” roaming the Pale of Settlement was a gross exaggeration, if not an illusion altogether. Against this newly gathered statistical evidence, they maintained the typology of “deserving poor” versus schnorrer. An early twentieth-century survey of Jewish poverty in Odessa registered seventy-nine beggars, including elderly, sick, and disabled people, all of whom desperately wanted to work. The authors took pains to differentiate these individuals from what was ordinarily understood by the term “professional beggar,” an “ill-willed, lazy parasite not willing to work by his own labor and preferring to live off of society.” Similarly, the editors of the survey of Jewish economic circumstances in the Pale conducted by the Jewish Colonization Association in 1898 and 1899 insisted that “it is not the love of idleness or ill will that pushes the poor Jew into a life of begging.” As in the Odessa survey, the social scientists almost pleaded with their readers to understand that Jewish beggars were those who could not work because of age or ill health. The Russian authorities believed that some Jews were guilty of parasitism and did not hesitate to arrest and prosecute those whom they considered to be vagrants (though there is no evidence that Jews were disproportionately targeted). In 1897, for example, one Movsha Mordukhov Frenkel (a.k.a. Grinberg), 27, was arrested in Kiev for vagrancy and sentenced to four years in prison, followed by exile to eastern Siberia.

Memoirs and anecdotal accounts of life in ordinary shtetls attest to the continuing presence of town beggars and vagrant mendicants. They do not always fall into the more “sympathetic” description provided by the JCA and Odessa researchers. One memoirist recalled that a poor man could not sleep longer than three nights in the hekdesh, so that poor people passing through town would have a place to sleep. The takanot (regulations) listed in the pinkas (record book) of the Hakhnasat ’Orhim brotherhood of Bar, held by the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv, refer specifically to poor people passing through the town. Who exactly is referred to by the phrase “the unfortunate poorfolk” (ha-‘aniyim ha-’umlalim)—described in the pinkas of the Bikur Holim brotherhood of the southern Ukrainian town of Balta as living in the town hekdesh—is unclear, but the pinkas gives no suggestion that they were divided into “worthy” and “unworthy.”

No matter how it was characterized, begging was and still is labor. As Fishke explains in Fishke der krumer,

My wife . . . showed me how to come into a house, how to moan and cough and look pitiful. I learned how to beg or even demand, how to stick like a leech and bargain for more, how to bless the giver, or to swear and curse with deadly oaths. Did you think that you can just start begging from house to house? Oh, no! There’s a whole science! (Fishke the Lame, trans. Gerald Stillman, in Selected Works of Mendele Moykher-Sforim [Pangloss, 1991], 236)

As Derek Penslar has shown in Shylock’s Children: Economics and Jewish Identity in Modern Europe (2001), through emigration, the Jewish poor of eastern Europe eventually became a problem in central Europe as well, where Jewish philanthropy directed much of its resources towards them. Immigrant aid workers employed by German and Austrian Jewish philanthropic organizations were told to be on the lookout for shysters, freeloaders, and criminals who sought only to leech off of communal finances.

After the First Zionist Congress in 1897 Theodor Herzl wrote in his diary that, despite appearances, he had “only an army of schnorrers.” The statement is revealing in its honest admission of how an assimilated, bourgeois Jew of Mitteleuropa viewed his eastern brethren. It is also more than a little ironic, for it was in part to solve the problem of Jewish schnorring in Europe—to bring about a new Jewish economic dispensation—that Zionism proposed to revolutionize Jewish life in the new society that it sought to create.

The charge of parasitism thus carries an extra sting in contemporary Israel, at least for some. Lest we think we have come full circle, however, the situation in Israel is quite different from that in Russia a century ago. An entire subgroup of society living off the state so that its menfolk can study Torah fulltime would have been impossible and indeed unthinkable in the czarist empire. In that place and time no Jewish faction or denomination could attempt to carve a separate space for itself in society. Whether Haredim will yet succeed in doing so still remains to be seen.