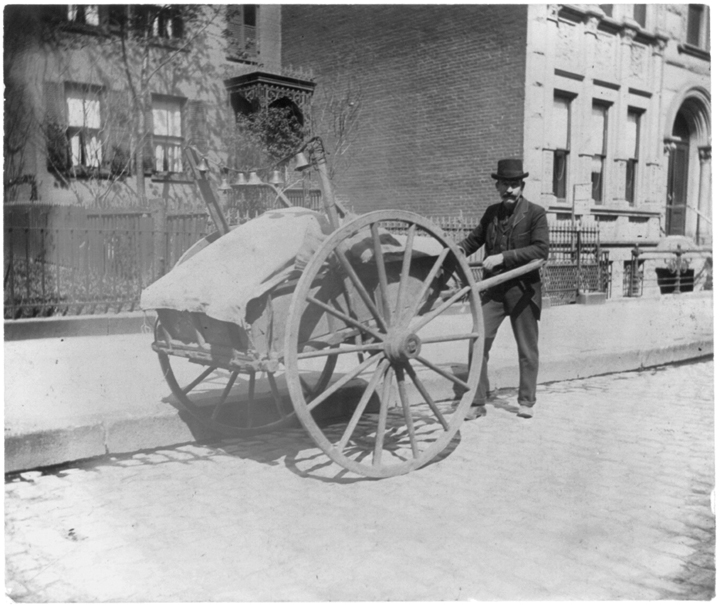

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov.

“A yid makht arbet,” a Jew makes work.

The answer may or may not be funny, but it points to the inextricable bond between life and labor, between existence and work. It assumes that work means making something—hence the verb makht—and takes for granted that the essence of work is producing tangible objects.

For much of Jewish history, Jewish work did not mean making something, but conducting the business which culminates the long process of making. Jews worked at buying the goods which someone made and then going out to sell them. Obviously millions of Jews did make things. Among other items, they made clothes. But the making of clothes could not have been accomplished without the commerce behind it. Most Jewish laborers who made products worked for Jewish employers, the capitalists who owned the factories, invested in the materials, stocked the machinery, paid the rent on the buildings, and yes, reaped the profits, whether modest or grand.

Jewish commerce has only recently become something that we study. It was a taboo topic in large measure because so many enemies of the Jews focused on their concentration in commerce. Critics of the Jews, whether intellectual, religious, or populist, accused them of not making anything, only engaging in the filthy business of business. Even where Jews produced things, they did not produce the things that the majority produced; that too set them apart, making them abnormal in the eyes of many among whom they lived. Many scholars have avoided labeling business as Jewish work, perhaps because so many of us are left of center on the political spectrum. We like workers, particularly those who joined unions, demanded humane working conditions, emphasized the dignity of labor and the positive bonds of the working class, and went out on strike, confronting their (Jewish) employers. They have been our heroes.

This is changing. The Center for Jewish History now runs a scholars working group on Jews and business. Yuri Slezkine’s stimulating, although problematic, The Jewish Century endowed the Jews’ history in business with great and transformative power. Slezkine argued that because they operated in the commercial zone, Jews had the freedom to innovate, migrate, and change the world. They may not have made many things, but they made the modern world. Not making things enabled Jews to move freely and cross boundaries.

Jews had peddled for centuries, certainly going back to the early modern period, and they did so all over the world. In some communities nearly all Jewish men peddled and some women did as well. My current project tackles this mundane yet historically rich form of Jewish work. First, a very quick definition as to whom I include as a peddler. “My” peddlers traversed the roads. They did not stand still on a street corner and wait for their customers to come to them, but put packs on their backs or got up on an animal-drawn wagon and went out to sell. They knocked on doors, crossing the thresholds of their customers’ homes. They went from house to house, building up a clientele who would, they hoped, keep buying new things. They returned to their homes once a week, maybe less often than that, depending upon the scope of their routes. Despite their obvious commercial activities, they made things, or better, they made things happen.

I am interested in the connection between Jewish peddling and Jewish migrations in the modern era, a time span that began at the end of the eighteenth century when the first contingent of Jews from Poland and Morocco went to England to sell goods door-to-door in small provincial towns.

Primarily, they brought domestic products to people who had previously not had access to these goods. The linkage between peddling and migration continued into the second and third decades of the twentieth century, as Jewish men tried their luck in places like Cuba, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and elsewhere in Central America. In between those two temporal book ends, Jewish migrations to the United States, Canada, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Sweden, all of South America, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, largely began with and flowed from the movements of peddlers. Peddlers as such founded all the new Jewish communities.

Everywhere they went, peddlers plied a weekly circuit. In Ireland they called them “weekly men,” and in parts of South America, semananiks, testifying to the ways they organized their time. They ideally slept in the home of their last customer of the day, and became fixtures of small towns, mining communities, plantation regions, and the like.

Because they had to engage with customers who spoke English, French, Spanish, Mayan, Swedish, Afrikaans, and so many other languages, peddlers became amateur cultural anthropologists. In order to make a sale they had to learn the tastes, prejudices, predilections, and sensibilities of their customers regardless of race, religion, or ethnicity. They likewise served as the interpreters of Judaism to their customers, women and men who likely had never encountered a Jew before. When the peddler demurred that he could not eat ham or other clearly forbidden foods, he had to explain that his religion did not allow him to bite into what his hostess had put on the table. At times they carried some food with them, while at other times they picked and chose what they believed they could eat among the foods their hosts offered them. Some peddlers left pots in their customers’ homes and cooked for themselves, and yet others decided that whatever food the housewife served, they would eat. Through small encounters, the peddlers made the Jews part of many strange new worlds. The peddlers played a crucial role in making new kinds of Jewish life, based in large part on the positive reception that they encountered as they went about doing their Jewish work.

Hasia Diner is professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies and History and Paul S. and Sylvia Steinberg Professor of American Jewish History at New York University. Her publications include The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000 (University of California Press, 2004).

Hasia Diner is professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies and History and Paul S. and Sylvia Steinberg Professor of American Jewish History at New York University. Her publications include The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000 (University of California Press, 2004).