From 1950–1951, some 120,000 Jews—approximately 90 percent of the total Iraqi- Jewish community (of whom the majority were Baghdadis)—left for Israel and the West in what Israel called Operation Ezra and Nehemiah and what the emigrants called the tasqit (shorthand for tasqit al-jinsiyya, the forfeiture of Iraqi citizenship required for exit). Iraq's few thousand remaining Jews would gradually follow, most fleeing the country after the Ba'th-sponsored repression of 1969–71, leaving only some twenty or thirty Jews in the capital to witness the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime in 2003. Whereas in 1950 there were some sixty synagogues in the city, by 1960 that number had been reduced to seven; the last functioning synagogue, in Betawwiyin (once a largely Jewish neighborhood), has been closed since the 2003 war due to security considerations.

It has often been said that New York is a Jewish city. I think one can safely say the same about Baghdad of the first half of the twentieth century. At the time of writing, barely twenty Jews, most of them elderly, live in my hometown. The one monument these Jews have left is a synagogue where, as their ancestors did from time immemorial, they keep praying for "the welfare of the city," as Jews in the Babylonian diaspora were bidden to do by the Prophet Jeremiah some three millennia ago. For those who, like myself, were born, grew up, and lived in Baghdad in the years preceding the mass exodus of Jews from Iraq in 1950–1951, this state of affairs is extremely hard to imagine.

The last two decades, however, have seen an unprecedented "return" of Jews to Baghdad in the form of novels, poems, documentary films, and memoirs. For these voyages of memory, Baghdadi-Jewish authors have utilized Arabic, Hebrew, French, and English, often reflecting the French and English influences many of the writers imbibed as students in Baghdad's elite Jewish schools.

The memoir has proved an especially popular route of return. Memoirs of life in Baghdad have been written by Naim Kattan (French, 1975; English, 1980; reprinted 2005); Anwar Shaul (Arabic, 1980); Yizhak Bar Moshe (Arabic, 1988); Esther Mercado (English, 1994; Hebrew, 1995); David 'Ivri (Hebrew, 2002); Sabiha Abdavid (English, 2003); Salim Fattal (Hebrew, 2003); Nissim Rejwan (English, 2004), Sasson Somekh (Hebrew, 2004; English, 2007); Badri Fattal (Hebrew, 2005); Esperance Cohen (Hebrew, 2008); Violette Shamash (English, 2008); and most recently, Shimon Ballas (Hebrew, 2009). It is striking that this list of memoirs (which is not exhaustive) contains a relatively high proportion of writings by women. Aside from the memoirs, related books in English include a 2009 collection of interviews with Iraqi Jews, edited by Morad, Shasha, and Shasha; Ariel Sabar's 2008 awardwinning memoir of his father's life in Kurdish Iraq; a 2006 cross-genre fiction and memoir by Marina Benjamin; and a 2000 autobiographical novel by Mona Yahya, an Anglophone Iraqi-Jewish writer in Germany (also the only work focusing on Jewish life in Baghdad in the post-tasqit period). These books are complemented by documentary films on the Iraqi- Jewish past, the best known of which, Forget Baghdad (2002), was directed not by an Iraqi Jew, but by an Iraqi-born Swiss director of Shi'i ancestry. Documentary films on the Iraqi- Jewish experience have been made also by the Israel-born director Duki Dror and the Iraqiborn Canadian director Joe Balass, both of Baghdadi-Jewish background.

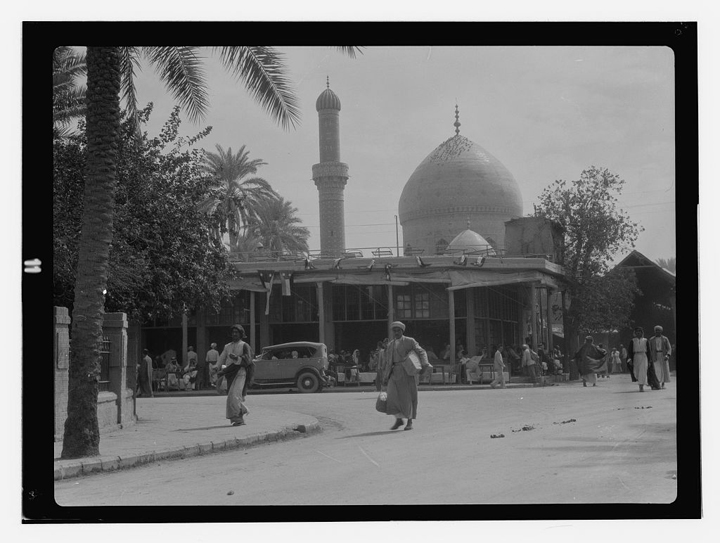

Given that the authors of the memoirs all left Baghdad as adolescents or young adults, their experience of the city is directly tied to their coming of age. Collectively, these narratives of childhood and adolescence create a lingua franca of shared experiences and places: sleeping on the roof on hot summer nights (Sami Mikhael dubs Baghdad "the city of rooftops"); Suq el-Hannuni, the noisy and bustling Jewish market; Rashid Street (then elegant, now decrepit), with its sidewalk colonnade of white columns; Egyptian musicals playing to adoring crowds in new cinemas; swimming in the Tigris (several male writers mention swimming from shore to shore as a Baghdadi rite of passage); picnics enjoyed on the river islands that emerged in the hot summer months. For budding writers such as Somekh, Rejwan, and Ballas, the experience of the city is also a discovery of its intellectual life, and so the excitement of the Baghdadi literary arena of the 1930s and 1940s colors their narratives. Above all, these works depict both the life cycle and the human subordination to nature epitomized by the then-mighty Tigris, whose central presence and whose seasonal rhythms defined the life of the city. Yet a subterranean current also runs through these Baghdadi-Jewish writings: that of an intense ambivalence on the part of the narrators (of memoirs and novels alike) toward the home from which they were essentially exiled. Jewish writings on Baghdad express a profound sense of identification interlaced with alienation—a kind of psychic split that culminates in the experience of witnessing the disintegration of Jewish life in the city in 1950–51 as the Jewish community departed en masse for Israel and the West.

In the aftermath of the 2003 war and intense sectarian violence of 2006–07, and continuing through the contested 2010 elections, Iraqi society appears to be disintegrating, breaking up into homogenous sectarian enclaves. In retrospect, the departure of the Jews from Iraq seems eerily prescient of the end of a multiethnic, cosmopolitan Iraq. All the while, Jewish writings on pre-1950s Baghdad continue to appear. Few of them mention present-day Iraq. But whether or not they acknowledge it, these works are intrinsically connected to present-day Iraq. To begin, their publication was facilitated largely by the post-1991 (and especially post-2003) surge of interest in Iraqi history and society, which created a writer's market, especially for history and memoir. One telling illustration is the reprinting of Naim Qattan's Farewell, Babylon, which was out of print for decades and then reissued in 2005 with a new introduction. The publication of memoirs can also be attributed in part to the current high demand for this genre. As for the books published in Israel, the post-1993 sociocultural shifts in Israel created space for a new kind of discourse on the Arab-Jewish past, one markedly less indebted to the Zionist metanarrative and more open to other histories and forms of affiliation.

The two Gulf Wars marked turning points in Iraq's history, and the latter definitively marked the "end of an era." The 2003 U.S. invasion also seems to have catalyzed the Jewish textual "return" to the Iraq of yore, for several reasons. The overthrow of Saddam Hussein and the Ba'th party inspired short-lived but fervent hopes of return visits by Iraqi Jews after a half century of exile— hopes that were quickly dashed by the rise of the insurgency. For Iraqi Jews, the war's bloody aftermath marked the final impossibility of return. The remaining Jews who came of age in Baghdad and remember it in detail will most likely pass away before it is possible for Israelis (or safe for other Jews) to visit Iraq. This realization imparts a sense of double urgency to the act of memoir writing: first, because it is only in texts that they can "return" and second, because this return must take place before it is too late.

It should be noted that the view of Iraq's past celebrated in these memoirs happens to dovetail with the neoliberal vision for Iraq's future advocated by the architects of the 2003 war. Regardless of one's position on the war and its aftermath, however, the fact of the matter is that in the halcyon days of Jewish life in Baghdad, the city was a thoroughly multiethnic and pluralistic space, and that it is becoming increasingly less so. The memoirs' obvious nostalgia for a cosmopolitan, multiethnic Baghdad is perhaps implicitly, if not explicitly, contrasted by a recognition of Iraq's current harsh and tragic realities. Yet the authors seem to see their experiences as relevant only to Iraq-of-the-past, without consideration of what their memories might imply, if anything, for the country's present and future. The very condition of these texts' enunciation— that is, the surge in popular interest in Iraq, its history, and society—is also the context with which they neglect to engage. In this way, the Iraqi-Jewish experience becomes curiously self-contained, as though it is the cultural patrimony of the Iraqi-Jewish diaspora, to the exclusion of other Iraqi peoples.

One might understandably protest: But is it relevant? If most Iraqi Jews parted ways with their homeland about sixty years ago, why should one expect them to maintain any sort of connection with a nation that has been hurtling along a vastly different cultural and political trajectory, one that seems to be divorced from the Jewish past? There might also be the temptation to contrast this situation with other historic contexts marked by rupture; to ask, for instance, what memoiristic writings of German Jews about Weimar Berlin might have to do with contemporary Germany. And furthermore, what about the flip side of this equation: Who in Iraq today remembers the Jews and their presence in Baghdad? What kind of interest do non–Jewish-Iraqi writers hold in the lost Iraqi-Jewish past? How, if at all, have Iraqis (both Jewish and non-Jewish) imagined Jews in the Iraqi present or recent past?

'Ali Bader, a young Iraqi writer (of Shi'i background) now living in exile in Brussels, has employed Jewish characters or made use of the Iraqi-Jewish past in at least two of his novels, Papa Sartre (Arabic, 2001; English trans., 2009), a satire on Iraqi philosophers in the 1950s and 1960s, and Haris al-Tibgh (The Tobacco Keeper, 2008) which narrates the life of a Jewish musician who was killed under mysterious circumstances in 2006. Another Iraqi expatriate, Khalid Kishtainy, has also frequently invoked the Iraqi-Jewish past. Sami Michael, the leading Iraqi-born, Hebrew-language writer, drew extensively upon the pre-1950 Iraqi-Jewish past in his earlier novels; but his 2008 novel Aida, set in Ba'athist Iraq, focuses on a Jewish television writer in 1990s Baghdad. As Sasson Somekh notes, both Bader's and Michael's characters are historical impossibilities. Yet the authorial creation of fictional Jews living in contemporary Iraq indicates a desire to envision Jews as part of the Iraqi present and future. As for memoirs, they are written as records of the past intended for future generations. To be sure, the Iraqi-Jewish memoirs, rich and nuanced as they are, offer a valuable refutation of dominant narratives and simplistic claims concerning Jewish life in Arab countries. But in twenty years, to whom will the experiences of Iraqi Jews, bound up as they are with that more cosmopolitan period of Iraqi history, be most relevant? I wager that the answer may not be the descendants of the Iraqi-Jewish émigrés themselves, but rather a generation of Iraqis that, emerging from the rubble of totalitarianism, dictatorship, war, and occupation, must take stock of and make sense of the history of modern Iraq and all the communities who have been part of it.

The ambiguous relationship of the Iraqi-Jewish past to the Iraqi national future is best illustrated by the bizarre story of the Iraqi Jewish Archive, which has received considerable publicity. In May 2003, U.S. troops seeking weapons of mass destruction waded into the basement of the former secret police (Mukhabarat) headquarters, which was flooded with sewage water. They found not weapons, but a cache of books, photographs, and documents— many of them printed in Hebrew. These included, inter alia, a 1568 prayer book, a damaged Torah scroll, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century books on Jewish law and commentaries, and fifty copies of a Hebrew- Arabic children's primer. The soldiers immediately realized they had stumbled across a treasure whose survival now hung in a very soggy balance. Inquiries revealed that these were private materials pilfered over many years from the Jewish community.

None other than Ahmad Chalabi, along with his friend Harold Krueger, a Jewish- American businessman, provided funds to drain the basement. The materials were dried in the sun, leading to mold, a preservationist's nightmare. They were subsequently packed into twenty-seven trunks, then loaded into a freezer truck to prevent further damage. Conservationists determined that the materials needed to be freeze-dried prior to restoration; with the agreement of the Iraqis, the trunks were transported to a Texas facility for freezing. From there, they were shipped to the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, where they were photographed and lightly cleaned.

The archive was supposed to be returned to Iraq within a few years. However, extensive preservation work is still required, the archive has not been digitized, and the necessary funds are lacking. In the meantime, the heads of the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center in Israel have claimed the archive for their museum, arguing that its contents were stolen from the Jewish community, whose members and descendants are now mostly in Israel, and who would be denied access to the archive were it returned to Iraq. However, the documents were removed from Iraq under an agreement that stipulated their future repatriation, and Iraqi officials have made clear that they view the archive as an important part of Iraq's cultural patrimony. In January 2010, Saad Eskander, the director of the Iraq National Library and Archives, told the Associated Press that the archives are needed to "show it to our people that Baghdad was always multiethnic," and to help them come to grips with their complex history.

Both the archive's convoluted path from Baghdad to Texas to Washington D.C. and its contested final destination raise questions of a political nature. First, why was such special attention given to these Jewish materials while important documents and books belonging to the Iraq National Library and Archives, which sustained catastrophic and irreparable damage, were neglected? And second, to whom do these documents now belong—if not legally, then morally? Beyond their most immediate political relevance, though, both questions also touch upon the relationship of the Iraqi-Jewish past to the Iraqi national present: a question that, to my knowledge, has not been addressed in a public forum, but which deserves consideration and debate. If and when Iraq achieves security, political stability, and genuine independence from the U.S., questions of the past—and the need to reckon with a new national narrative— will undoubtedly occupy a prominent place in its civil society, and Baghdad's Jewish legacy will inevitably play a role therein.