Many American men of a certain age can recall the surge of anxiety that coursed through their bodies upon receiving a thin envelope from the Selective Service System, ordering them to report for induction into the United States Armed Forces. For those who served in the Second World War, anxiety was often countered by patriotism and hatred of the enemy. Those who were drafted to fight in Korea and especially Vietnam were more likely to see conscription as a curse rather than an obligation. Still, even in the unpopular Vietnam War only about 10 percent of those who were called up dodged the draft. War is frightening, but dodging the draft is usually more frightening still. Patriotism, social conformism, the fear of punishment or of being shunned, and masculine pride kept most young men from taking that fateful trip to Canada.

"Vi es kristelt zich azoy men yidelt zich," as with the Christians, so with the Jews. Since the introduction of conscription in Europe towards the end of the eighteenth century, millions of Jews throughout the Diaspora have performed military service—often unwillingly, at times enthusiastically, but usually obediently. To the extent that Jews did try to evade the army, they differed little from many others. (In Austria-Hungary in the early 1900s, draft-dodging rates were highest in the empire's Balkan and Italian territories, where few Jews lived.) Yet for Jews, military service evoked horrors even greater than deprivation and mortal danger.

Particularly in eastern Europe, the demographic center of the modern Jewish world prior to the Holocaust, the army threatened not just Jews but Judaism itself. Long terms of service, conversionary pressures by hostile commanders, and limited access to kosher food or Jewish learning threatened to turn generations of young Jewish men into ignoramuses or, worse yet, Gentiles.

Jewish anxiety about the military precedes modern conscription by several centuries. In medieval and early modern times, some of the most famous illuminated haggadot represented the ben rasha'a, the wicked son, as a soldier. Jews certainly had a heritage of fighting—as warriors in biblical antiquity, and from the Middle Ages onward as defenders of towns and cities in eastern Europe. But at a time before conscription, when soldiering was a profession practiced, as Machiavelli tells us in The Art of War, by the crudest of men, Jews had fear and contempt for those who lived by the sword. Rabbinic Judaism was not pacifist, but it translated physical into verbal aggression, substituting talmudic disputation for swordplay.

Jews were first conscripted by command of the Hapsburg Emperor Joseph II in 1788. In April of the following year, as twenty-five timorous Jewish recruits assembled in Prague's Old Town, Rabbi Yehezkel Landau handed each soldier a prayer book, a packet of tefillin, and a packet of tzitzit, after which he told them: "Go forth to your fate, follow it without protest, obey your superiors, be loyal out of duty and patient out of obedience. Yet forget ye not your religion, do not be ashamed to be yehudim among so many Christians." At the end of his speech the rabbi began to sob, and young soldiers and their parents made tearful farewells.

Almost a century later, in the Russian Empire a similar spirit of grim obedience to fate suffused the most important rabbinic treatise on military service, Sefer Mahaneh Yisra'el by Yisra'el Meir Kagan, known as the Hofez Hayim. The rabbi urged soldiers to follow Halakhah as carefully as possible, even in the heat of combat, when the temptation to engage in sexual impropriety and other heinous acts might be particularly great. In spare but foreboding language the rabbi instructed Jewish soldiers preparing for battle to confess their sins and to be prepared for death. Why, one might ask, did the rabbi not counsel young Jews to steal across the border rather than report for induction? Privately, he very well may have done so, but no public figure would dare flout the tsar's law. And although some Russian Jews did dodge the draft, the vast majority did not, and the Hofez Hayim's little volume was a source of comfort and calm at a time of the utmost anxiety.

While Jews in eastern Europe feared lest the army tear their communities asunder, in Germany and western Europe Jews experienced a very different sort of worry. In the first half of the 1800s, rabbis in Prussia urged the government to draft the Jews so that they could prove their worthiness for emancipation. At a time when middle-class German Christians were cutting off their trigger fingers to avoid the draft, German Jews were clamoring to be put into uniform. Only by fighting for their country, so the idea went, could Jews overcome accusations of dual loyalty, cowardice, and effeminacy. During the Austro-Prussian and Franco- Prussian wars German rabbis and activists painstakingly counted the number of Jews in uniform, especially those who were decorated for heroism or who died in battle. This use of statistics as an apologetic tool would be repeated during the First World War and well into the 1930s, when the 12,000 Jewish war dead were repeatedly, futilely, and pathetically invoked as a defense against the theft of their rights of citizenship at the hand of the Nazis.

In France, in contrast, by the second half of the 1800s the Jews' social position was increasingly secure, and grateful young French Jews flocked to serve in their country's military at home and in in its growing overseas empire. In the 1890s growing anti-Semitism caused French Jews to protest their love of country all the more volubly. The arrest and conviction of Captain Alfred Dreyfus on charges of espionage sent French-Jewish anxieties skyward. In 1898, Fernand Bernard, a Jewish army captain serving in Indochina, wrote to his brother, the famous writer Bernard Lazare, that he was disgusted to wear the same uniform as that of Dreyfus's tormentors and was considering resigning his commission: "Where is my former pride, my former faith? I ask today only to leave the army and be me, Fernand Bernard, and not Captain Bernard."

Dreyfus was eventually exonerated, calming the frayed nerves of Jews the world over. But less than a decade later the Great War stoked an utterly different kind of anxiety among Jews in the lands of the Entente and Central Powers alike. Could it happen that Jews on different sides might kill their coreligionists? Fears of such unintentional fratricide dated back to the 1848 Revolutions, when Jews both fought as rebels and served in the imperial armies that suppressed them. From the 1860s onward stories abounded about a Jew who killed, or almost killed, a Jew who became recognizable by his (dying) declamation of the Shema Yisra'el or a Magen David around his neck. In the First World War, such stories were legion, on the eastern and western fronts alike. The stories' facticity is doubtful, especially since the vast majority of combat deaths on the western front were by machine gun and artillery fire, not hand to hand combat. But they are meaningful myths, expressions of a profound Jewish transnational solidarity even while asserting patriotism by fighting and dying for their homelands.

In a bitter irony, the Second World War, during whose course two-thirds of the Jews of Europe were slaughtered, was in certain ways the least anxiety-provoking war for Jews in modern history. There was a clear enemy, and Jews the world over fought on one side—that of the Allies against the Nazi Amalek. In the United States, there were, on a per capita basis, far fewer Jewish conscientious objectors than Christian ones. Of course Jewish men were still nervous about going off to fight, and Jewish mothers were loath to send them into danger. The mother of Meyer Birnbaum, an Orthodox Jew from New York City, urged him to flee the draft, but he consulted on the issue with his rabbi, who sat him down with the Hofez Hayim's Sefer Mahaneh Yisra'el and told him that dodging would be hilul ha-shem, desecration of the name of God. Thus fortified, Meyer went off to war, where he served with distinction and rose to the rank of lieutenant.

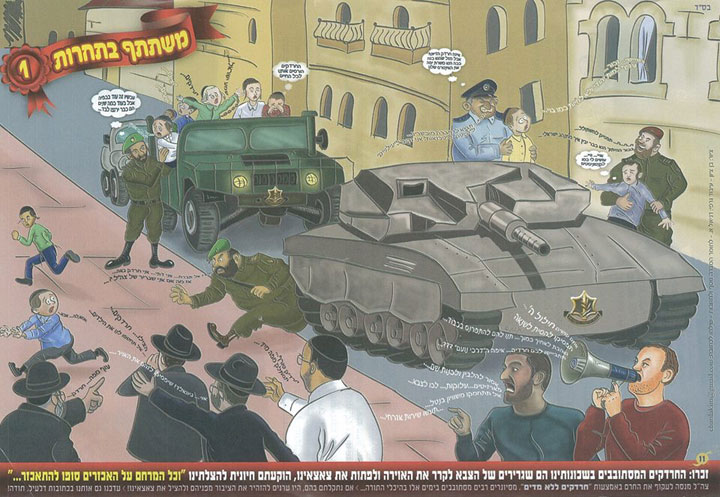

Even in our own day, where the State of Israel has a powerful army in which most young Jews serve, distant memories persist from the Russian past, of the terror of donning a uniform, hoisting a rifle, and worst of all, leaving behind the sheltering and sustaining confines of the Jewish community. During recent debates about the conscription of ultra- Orthodox (Haredi) Jews, Haredi opponents of the draft have distributed flyers decrying what they call hardakim (Haredim kalim, or "Haredim lite") who conspire with the evil state (this time, the Jewish State of Israel, not tsarist Russia) to snatch tender young Haredi boys and dispatch them to the army. (See figure.) In time, no doubt, more Haredim in Israel will do some kind of national service, which they will not dodge any more than was the case for the vast majority of Jews, including the strictly Orthodox, throughout modern history. But fear is a strong as life; memory belies history. Although Jews are more prone to fetishize the IDF as a symbol of collective strength than to condemn it as an agent of brutality and assimilation, Israel's armed forces have not put an end to Jewish anxieties about military power.