As trained musicologists, perhaps my colleagues and I have been complicit in cornering the field, building a wall of specialized vocabulary and skills around sonic phenomena (music theory, anyone?). But I think the matter goes far beyond scholarly monopoly. Music and sound are tough to pin down and hard to control and this slipperiness can trouble an academic field deeply (overly?) invested in the written word. Sound in this environment tends to receive awe or be regarded as novelty, though too often that means exclusion. Yet without sound, are we really doing justice to the full subject of Jewish Studies?

It's both illuminating and maddening. We live in sounds. Sound accompanies every moment, every setting, every social situation, every act. It coordinates ears and skin (or one or the other) and translates vibrations into meaning. Barring a perfect vacuum, moreover, even the most soundless of silences is a conceit. Postwar composer John Cage highlighted this idea in his performances, most famously in his piece 4'33": revealing how the unfulfilled expectation of a "performance" yields a more layered complexity of ambient sound. Humanity operates by creating, regulating, and responding to its own sounds, acknowledged or unacknowledged, intentionally or unintentionally. We can't escape them, even as they confound our ability to describe them.

How people shape, interpret, and respond to those sounds presents a rich and still-developing area, and a challenge to the current state of our field. As a historian, I go searching for echoes in documents, memories, notation, recordings, ephemera, and musical instruments. As an ethnographer, I go where sounds happen, experiencing them when I can to see Jewish discursive patterns in action. They're not easy to avoid; and by listening carefully, we have an obligation to figure out how those sounds generate significance in context.

In doing so, each group included some sounds as "Jewish," and excluded others. More significantly, these approaches valorized specialized musical training as the necessary skill for discernment. Today, recognizing the idiosyncratic lacunae such efforts created, scholars of sound aim to swing the pendulum back somewhat: to reopen productive dialogues with historians, cultural theorists, philosophers, theologians, and others in the world of Jewish Studies. Aided by the many technologies we now have to preserve sound, including about 1,400 years of musical notation, a century of media recordings, seventy years of "earlyadopter" consumer-grade recordings, and at least a decade where audio/video collection is more convenient and immediate than writing itself, new explorations can perhaps rebalance sound as a normal and accessible component of experience: continuous with other written materials that have served as the backbone of our scholarly pursuits.

To see how this process works, look to the celebrated writing of my mentors and colleagues: Kay Shelemay on the Beta Israel populations; Mark Slobin on Yiddish theater and cantors; Edwin Seroussi on music of Jews of North African and central Asian heritage; Mark Kligman on Syrian Jews; James Loeffler on the late Russian Empire; Tamar Barzel on the downtown Manhattan avant-garde scene; Evan Rapport on the Bukharian Jewish diaspora; Philip Bohlman on central Europe; Klara Moricz on the turn of the twentieth century; Tina Frühauf on the centrality of the organ; Lily Hirsch on Holocaust-era orchestras; Amy Horowitz on Israeli popular music; Josh Kun on American popular music; and a bevy of others. All bring sound to bear on the intersection of history and identity using increasing precision and depth, inclusively integrating sonic materials into broader political, historical, and cultural frameworks.

And sound, with its unique qualities, has much to say. I spent three years learning, talking, and performing with cantorial students at Hebrew Union College to understand the role of sound in considering Reform Jewish life and history. Taking notes and (authorized) recordings along the way, I witnessed students combining artistic, historical, and theological perspectives in intensive dialogue with mentor-cantors, rabbis, educators, voice teachers, and musicologists. And the closer I came to the sound, the more it became a complex entity of dynamic, moving strands. Looking at each strand, with the help of sources such as sheet music, course catalogs, and recordings, illuminated a textured, twentieth-century history of musical definition and redefinition, as liberal Jewish leadership looked to elevate sound as a component of spiritual authority. While many know sound's power as an aesthetic strategy for promoting identitybased historical narratives—at concerts, say, or in the service of religious ritual— intimacy with the same sounds became here a clarifying lens into an overlooked yet ever-present part of Jewish life.

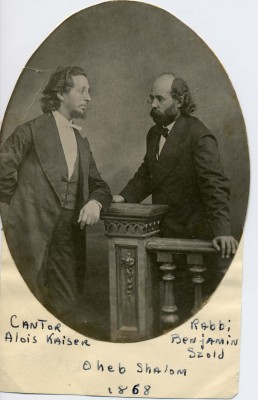

Sound opened up realms of popular culture as well, expressions often cordoned off by ornamental critiques of unseriousness or inappropriateness, or solely analyzed by lyrics. Cantorial schools, for example, faced dilemmas in addressing liturgical music based in folk or rock styles that clashed with historical Jewish music narratives, even as they comprised the majority of congregational sound. Attributed to major progenitors such as Debbie Friedman and Jeff Klepper, the music's proliferation in the late twentieth century became a source of cantorial frustration and/ or moral consternation, symptomizing the potential loss of Jewish musical identity. Approaching the topic through sound helped me to understand the deep-rootedness of this debate as a centuries-long cyclical exercise of pitting musics of tradition and innovation against each other in an existential battle for Jewish cultural primacy—and in each case reaching détente after decades of negotiation. Sound in this context became a central criterion for understanding the dynamics of liturgical practice: as musicians such as Debbie Friedman and Ben Steinberg joined liturgists such as Benjamin Szold and Adolph Huebsch as central figures in determining the dynamics of religious communal life.

Similarly, sound's deep and longstanding integration into performance-based arts such as theater offers opportunities for new angles of understanding. Preconceived notions of musical theater's so-called "light" entertainment, to give one example, tend to obscure the vast landscape of experimentation that "the musical" entails, especially when Broadway and its commercial implications cease to be the dominant point of reference. When, in presentations, I note that Anne Frank's diary has become the subject of at least fifteen musical theater works, I occasionally face pushback about musical artists' "commercial appropriation" of a central Holocaust symbol. The picture looks different, however, when viewed from the perspective of the artists, some of whom have devoted decades to these works, have extensive training and facility with musical models and histories, choose every note for a reason, and treat their work as a living, dynamic thing that changes from audience to audience. Their articulate responses speak to a wide range of composition and mediation, and show sound as both generative and responsive to human interaction.

In all of these cases, sound becomes a mode of philosophy that constructs its own worldview: defining the past and acting on the present, acknowledging in the process the richness of the moment and its echoes across Jewish life. Accessible—or rather, inescapable—sounds hardly require special talent or training to explore, only a willingness to consider how the senses fill meaning. With the state of digital humanities expanding rapidly, methods and colleagues available to consult, and broader openness among scholars to engage in arts-associated projects, the scholarly immediacy of sound may, hopefully, become as natural to us as it is in real life.