Thus, for example, I have delivered a public lecture entitled “Scroll Down: Classical Jewish Texts, from Parchment to the Internet” (with its intentionally catchy, clever title) at Oxford, Birmingham, UCLA, Catholic University, and Rutgers; twice I have taught a course for Jewish Studies undergraduate majors and graduate students on the subject; and I have segued from my own core research in the areas of Bible and Hebrew language to several recent publications on specific issues in medieval manuscripts.

Most importantly for the present essay, these manuscripts have informed my teaching, not only with such obvious courses as “Introduction to the Bible” and “The Dead Sea Scrolls,” but most significantly with “Jewish History I: Ancient and Medieval.” This latter course, which serves as the Jewish history survey course (part 1) here at Rutgers, includes the Middle Ages (per the title), concluding with the year 1492. Through images of medieval manuscripts, I make the life of late antique and medieval Jewry come alive.

The Mishnah is no longer just the earliest rabbinic text, but we also marvel at its later manuscript tradition, especially by examining the Kaufmann manuscript (Budapest) at http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/. The Talmud of the Land of Israel (Leiden manuscript) is inspected here; while the Babylonian Talmud (Munich manuscript) is examined here. Even if the students cannot read Hebrew, they are able to appreciate these texts, the size of each compilation, and the history of their transmissions. They no longer are abstract compositions, which appear in book form, usually as a series of printed books on a bookshelf (which immediately removes them from their historical setting). Rather, these classical rabbinic texts now are understood as words written in ink by a scribe on vellum or parchment (even if in these cases the original compositions were transmitted orally for generations). Whether my students are Jewish or non-Jewish, knowledgeable in Hebrew or not, they are all able to recognize the expert scribal hand responsible for the Kaufmann Mishnah manuscript.

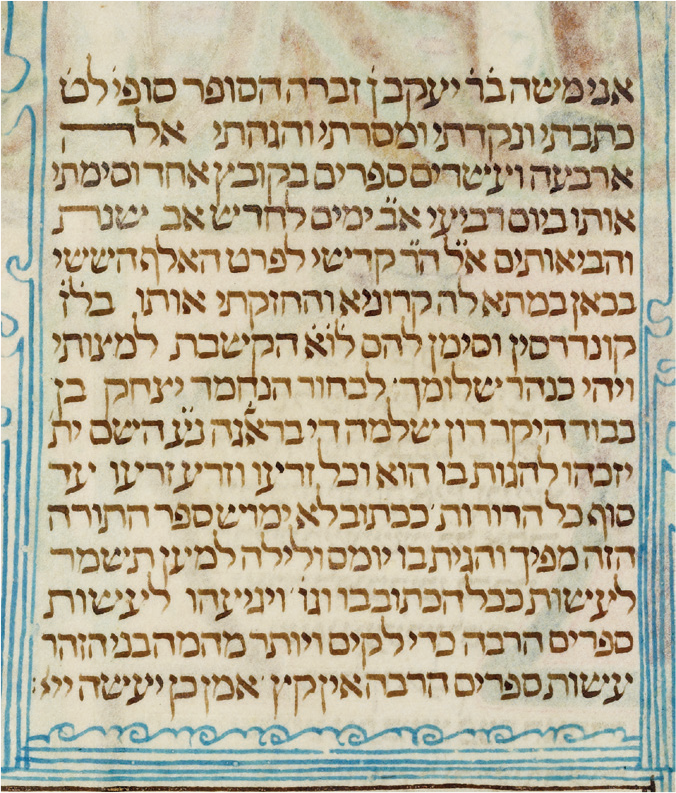

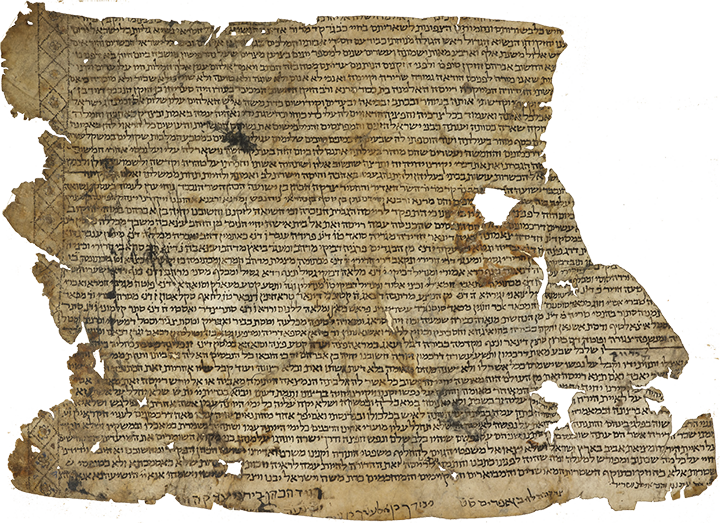

There is, moreover, an important history lesson that can be learned by reading the Mishnah manuscripts (Kaufmann and others). I direct the students’ attention to the statement in M. Sanhedrin 4:5 (fig. 1). The printed editions from the sixteenth century onward read, “One who destroys a life within Israel, he brings upon himself the saying, ‘It is as if he has destroyed an entire world.’ And one who raises up a life within Israel, he brings upon himself the saying, ‘It is as if he raised up an entire world.’” When one looks at the manuscripts, however, one realizes that the phrase מישראל (“within Israel”) is lacking. These documents testify to the real world view of the rabbis: every single human life—Jewish or non-Jewish—is to be valued.

How does one explain the addition of מישראל (“within Israel”) in the printed editions (which persists to this day; see, for example, both in the widely used Albeck edition and at Sefaria [www.sefaria.org])? My proposal is that centuries of medieval antisemitism, especially within Christian Europe, led the Jewish community to have a less sanguine attitude toward the value of the lives of non-Jews. Blood libels, accusations of host desecrations, rampant killings, inquisitions, expulsions, and more had taken their toll. The Jewish community turned inward, away from the universalist outlook expressed by the classical rabbis. The great ecumenical ideal enunciated in the Mishnah was transformed into a parochial statement by later Jews: what a teachable moment.

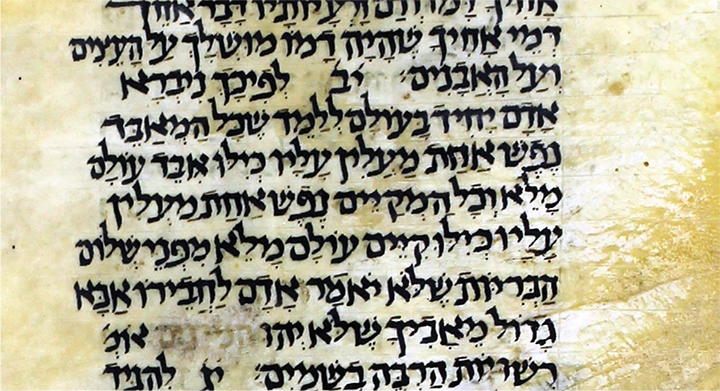

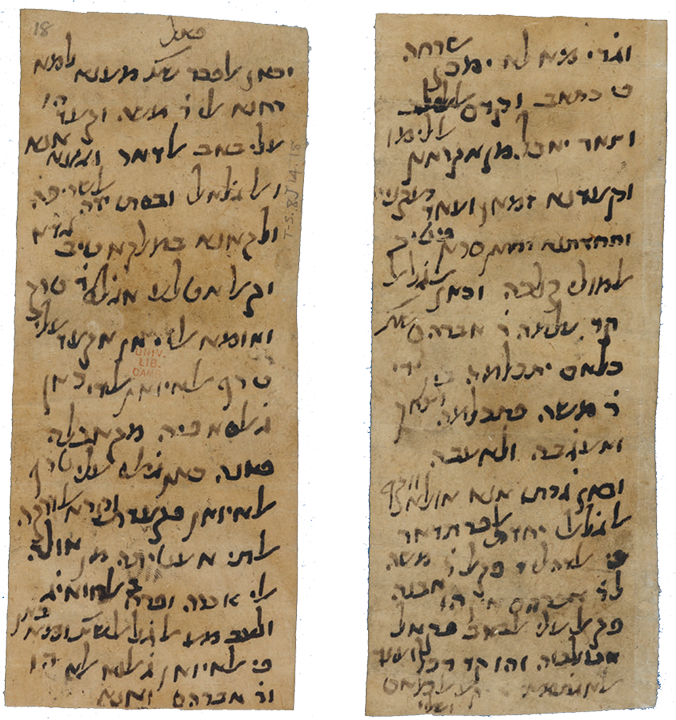

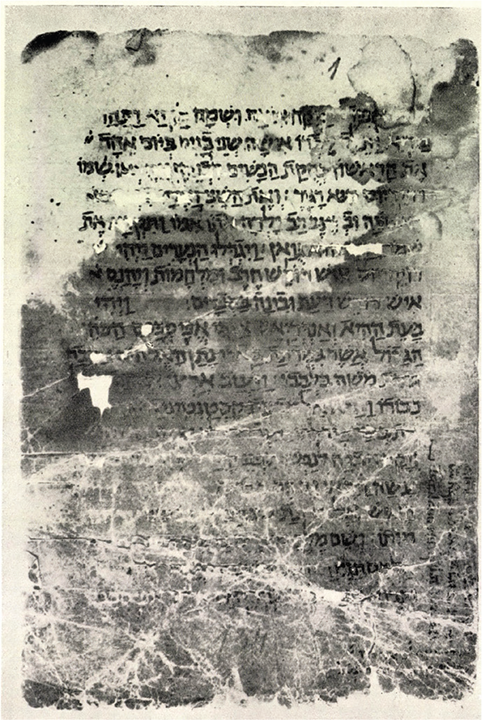

As indicated, the manuscripts for the Mishnah, the Talmudim, and other rabbinic compilations are dated centuries after the composition and final editing of these texts. When we reach the Middle Ages in our course, accordingly, the characters whom we study truly come alive through our inspection of the manuscripts. Judah ha-Levi is not just the author of the great philosophical work ha-Kuzari, who left his native Spain to travel to ’Erez Yisra’el, but he is the one who personally penned the Cairo Geniza document J.T.S. ENA I.5 (L41), a letter addressed to a colleague, in which the author mentions both the book and his travel plans (fig. 2). This document, along with all the Geniza documents noted below, are available at https://fjms.genizah.org/, from which I capture the images for educational purposes.

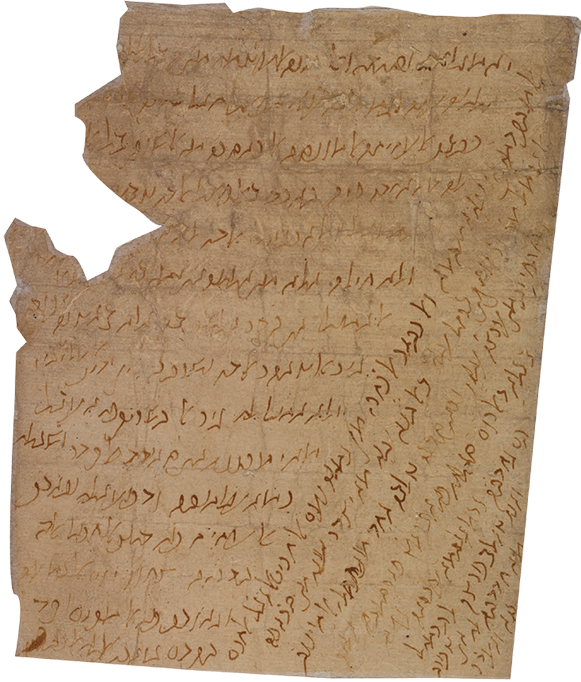

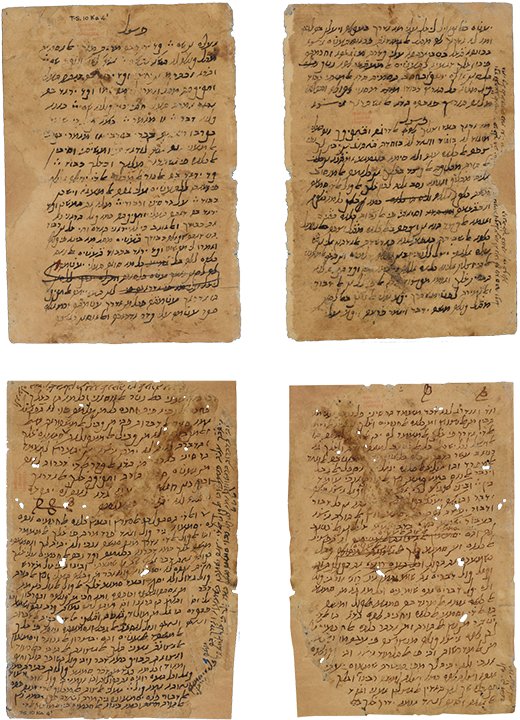

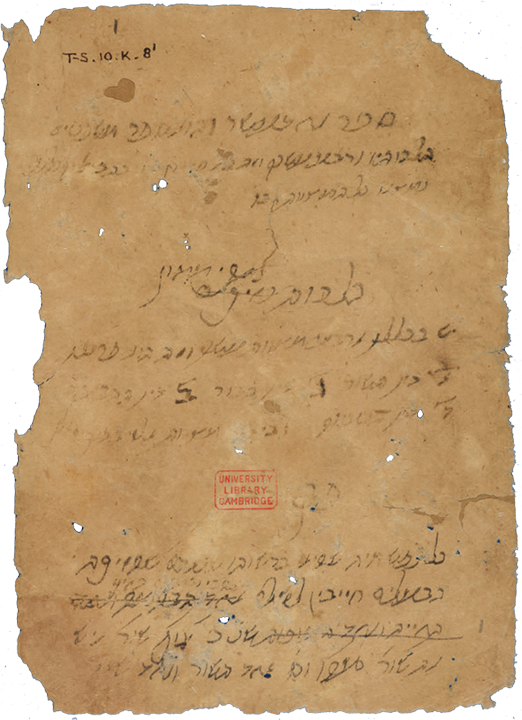

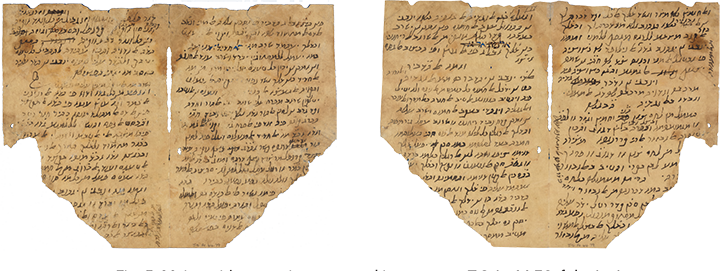

The greatest of all the medieval sages, Moses Maimonides, is, of course, even better represented among the Cairo Geniza documents. I show my students: (a) a draft of the philosopher’s Judeo-Arabic original of the Guide for the Perplexed (C.U.L. T-S 10.Ka.4.1) (fig. 3); (b) a draft of the legal scholar’s Mishneh Torah (C.U.L. T-S 10.K.8.1) (fig. 4); (c) the physician’s Judeo-Arabic treatise on sexual intercourse (C.U.L. T-S Ar.44.79), addressed to Sultan al-Muzaffar Umar ibn Nur Al-Din (nephew of Saladin) (fig. 5); and (d) an insight into the community leader’s personal life, to wit, the report of a visitor to his house (C.U.L. T-S 8.J.14.18) (fig. 6).

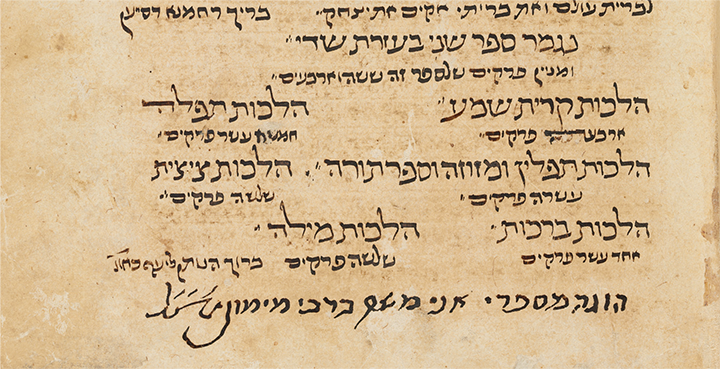

Beyond the Cairo Geniza documents is one of the most precious of all the medieval manuscripts, namely, the Bodleian Mishneh Torah manuscript (Huntington 80), with its own dedicated website. A professional scribe wrote the beautiful manuscript, but in the white space at the bottom of folio 165r, at the end of book 2, the great sage himself wrote, in his own hand, הוגה מספרי אני משה ברבי מימון “checked against my copy [lit. book], I, Moshe son of Rabbi Maimon.” An entire backstory is created thereby: Maimonides drafted the work in his rather quick and cursive hand (recall the Cairo Geniza documents); he gave it to a professional scribe in order to produce the definitive edition; and he then checked and proofread the entire work, with approval, as indicated by his personal imprimatur at the bottom of folio 165r (fig. 7).

But to return to the aforementioned report of the visitor to Maimonides’s home, C.U.L. T-S 8.J.14.18, I tell my students: “Right, so Maimonides wrote the Guide for the Perplexed, and he wrote the Mishneh Torah, and he served as physician to the sultan, and he served as head of the Jewish community in Cairo—but I want to know what he served his guests!” And thus we read in the afore-cited document, which provides a unique window into Maimonides’s own home, “I kissed his eminent hand, and he received us very warmly. . . . Then such things happened that are impossible to describe in a letter. Baskets arrived and he began to eat lemon cakes” (translation adapted from here).

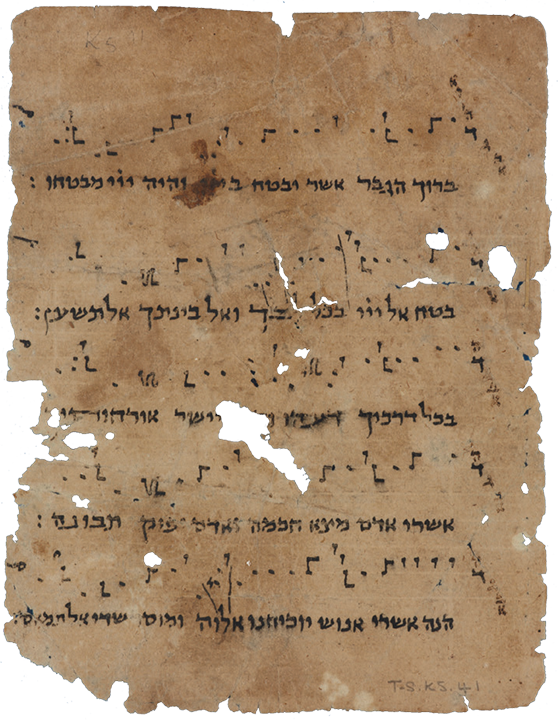

And so we proceed. It is not just a matter of discussing Rabbanite-Karaite relations in the Middle Ages: I show the students examples of ketubot indicating marriage between the two groups, including Bodleian MS Heb a.3.42, recording the marriage of Yahya ben Avraham (a Rabbanite physician) and Rayyisa bat Saadia (a wealthy Karaite woman) (fig. 8). Similarly, it is not just a matter of discussing conversion between Judaism and Islam (in both directions) and between Judaism and Christianity (ditto): I show the students the memoir and musical compositions of Johannes of Oppido = Obadiah the Proselyte, that is, Budapest 134 1r (the beginning of the memoir) (fig. 9) and C.U.L. T-S K5.41 (with the prayer ברוך הגבר set to Gregorian chant) (fig. 10). Again, whether or not the students can read Hebrew is not the point; rather, each of them is able to enter the world of the Middle Ages by viewing these documents firsthand.

As we end the course with the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, in an effort to give the students a sense of how wealthy and prominent the community was, I end the semester with images of the Kennicott Bible, written in La Coruña in 1476, now housed in the Bodleian Library. Everything about this work is simply exquisite: the biblical text, the accompanying masorah, the inclusion of David Kimhi’s Mikhlol, the penmanship of the scribe, the illuminations of the artist, and the colophons that preserve the names of both individuals, along with other valuable information (date, place, name of benefactor, etc.) (fig. 11). Once more, an entire world, that of northern Iberian Jewry, unfolds in the most vibrant of colors by studying this unsurpassed masterpiece. The Kennicott Bible marks the pinnacle of the Jewish manuscript tradition, the culmination of centuries of codex production, on the cusp of a sea change in Jewish history, and on the cusp of the beginning of Hebrew printing. And with that, the students are ready for “Jewish History II: Early Modern and Modern.”