For the last ten years, as Sol Drachler Professor of Social Work and Professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, I have had the privilege of deepening my students’ understanding of Jewish history and identity while preparing them to address the challenges of contemporary Jewish life. Given how similar this project is to where I started, twenty-seven years ago, teaching student rabbis at Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC) in Cincinnati, I may appear to have traveled a smooth path to my current position. I did not.

Arriving in Cincinnati in 1991, I became the first woman to hold a tenure-track position on that HUC campus. I hardly felt like a pioneer. At that point, it seemed late in the game for this kind of advance—after all, Sally Priesand, who had studied in Cincinnati, had been ordained as the first American woman rabbi twenty years before I got there, and both the New York and Los Angeles campuses of HUC each already had one woman on their faculties. So, people were less impressed than shocked to learn that I was to be the campus’s first woman faculty member. Cincinnati faculty explained that theirs was a small cohort and there were few women in the text-focused academic fields that dominated their ranks. Meanwhile, many of the school’s women students felt frustrated that people considered them “women rabbis” as opposed to just “rabbis.”

I quickly fell in love with the school’s history and curious cast of characters, the pride that local folks took in the college, and the library’s large bound volumes of nineteenth- century periodicals. I felt honored to join this historic campus and to teach its students.

It seemed fitting that I was completing a dissertation focused on how eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American Jews adapted Judaism to address changing expectations for women, with much of my research focused on the nascent Reform Movement and its organizational home in Cincinnati. It did not escape me that my own presence was pushing present-day HUC to adjust in ways both large and small (a lock on the faculty’s bathroom door!). More than anyone, I was aware of how often the Reform Movement’s historic rhetoric of gender equality had repeatedly failed to match reality for women within its reach.i Still, I hoped I could become a small but positive footnote in the history of this venerable institution.

I felt confident in my ability to navigate these waters. I had long dwelt in institutions marked by male academic privilege. My undergrad school, Yale, had gone coed only ten years before my arrival, and I was coming from an American History graduate program at Harvard dominated by male faculty and students. As the youngest, only unmarried, only gay (though not comfortable or out in that setting), and only woman faculty member, I knew there were myriad ways in which I didn’t belong, but I never had trouble finding my place in male worlds. My expectations, moreover, were shaped by the example of my academic parents. Starting out in the 1950s, my mother, a true pioneer, had rarely seemed ruffled as she raised four children and became a leading scholar of modern Chinese history. My parents never focused on traditional femininity as the way to success, and I understood from them that academics were judged according to the merits of their contributions. Hence, I wasn’t worried about appearing too forthright or questioning. I understood those traits as among my strengths, as they had been before my time at HUC and would prove to be again after.

Accordingly, I fully embraced the opportunities offered by Cincinnati and HUC. I spent days, weeks, and months in the American Jewish Archives, completing my dissertation and then my book manuscript, while enjoying the added benefit of being able to welcome, host, and learn from visiting scholars from around the world. The archives also became a home for further research and publishing on the history of the Cincinnati Jewish community, American Jewish liturgies, and the history of the relationship between HUC and the Jewish Theological Seminary. I developed courses that brought students beyond the institution’s walls—on one notable occasion, for instance, bringing my students from a course on blacks and Jews into a remarkable dialogue with the adult education community of one of the city’s African-American churches that dwelt in a former synagogue building. Indeed, studying the experience of Cincinnati’s black churches whose homes were in former synagogue buildings yielded both precious relationships and a published article.

I developed relationships throughout the community and with colleagues at the University of Cincinnati. Among many other communal endeavors, I joined the effort to build a museum dedicated to the history of the Underground Railroad in Cincinnati, cochairing its history advisory committee. HUC’s particular and unique community was especially precious to me, and I regularly attended worship services and community events. I took a leading role in working with students to deepen communal engagement through service projects, community conversations, and inviting outside speakers on current vital subjects that were missing in the standard curriculum. Opportunities to create and participate in this rare sort of engaged community were what made me prize the Cincinnati campus of HUC as a special learning environment, beautifully suited to immersing students in both meaningful community and critical thought. I also participated fully in faculty discussions, service roles, and in publicly representing the school, always with an eye to seeing us fulfill the potential of our singular history and current possibilities.

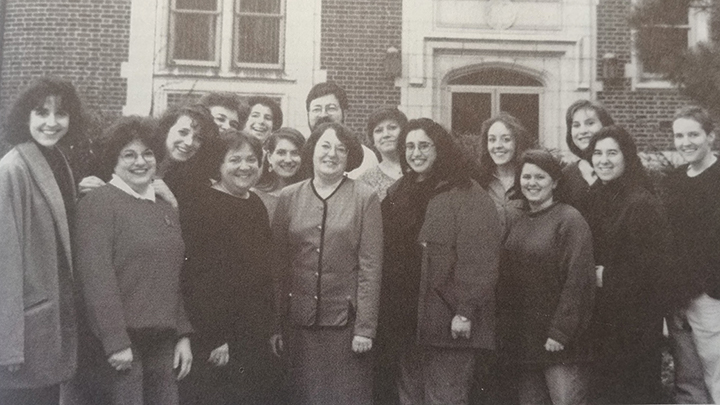

In 1998, when I organized the third biennial Scholars Conference on American Jewish History, I relished the opportunity to introduce my colleagues to a special school and community. The conference is still fondly remembered by those who were there for its challenging program, its deep immersion in the rich history and texture of HUC and Cincinnati, and for a remarkable keynote by playwright Tony Kushner, who had struggled through a cross-country odyssey, buffeted by fierce rain storms, to get to us.

So, in 2000, when I was denied reappointment after nine years at HUC, I was deeply stunned and bereft at the seeming erasure of all I’d done there. Indeed, it has taken a long time for me to recognize that I could be valued for the very skills—teaching, administration, public speaking, collegiality—that those who determined my fate at HUC decided I lacked. Although the committee, when asked directly about my research and writing, acknowledged that my scholarship met their expectations, I was still left feeling, for years afterward, that I needed to prove myself on that score as well.

Why revisit all this now? As the fractures that emerge when women enter settings once reserved for men come increasingly into clear view, it becomes easier to see how women who run into trouble in these environments are blamed for their inability to fit in. HUC’s leaders were outraged when, in the face of my dismissal, people questioned their commitment to gender equality. Given that, very soon before, the first woman faculty member at HUC’s New York campus had been denied tenure and New York’s first female dean had been dismissed, it seemed a fair question. Yet, rather than acknowledge the possibility of legitimate concern, they questioned the loyalty of those who objected. They absolved themselves of responsibility, while disempowering those who suggested the school could do better. As faculty at HUC or rabbis in the Reform Movement, women who talked (even with each other) about being treated badly or inappropriately could risk current or subsequent jobs. In relatively closed systems like the Reform Movement or Jewish Studies, few could afford to disrupt upbeat institutional narratives.

In 2004, I accepted a settlement in a lawsuit I had brought against HUC for wrongful dismissal. I refused, however, to accept a provision that would have prevented me from writing about my experiences there. Today, as I watch courageous women stepping forward to call the Jewish community to account for overlooking the transgressions of powerful men, it seems like high time to set the record straight about my own experience.

My early years as the only woman faculty member on campus yielded many strange experiences. Others would occasionally call attention to my awkward position, as in my second year, when one professor beseeched his colleagues to cease what he called the “puerile practice” of addressing each other as “gentlemen” at faculty meetings. The practice shifted after that, but not without someone first responding, “oh, I’m sure Karla doesn’t mind.”

I quickly became aware that many faculty members, most of whom were HUC graduates, simply could not recognize the vulnerability of those who did not experience themselves as insiders. I would often see faculty dismiss the efforts of students who questioned the campus culture. When I highlighted the courage it took for a student to, for instance, facilitate a conversation about gender inequality at HUC, they would respond, “Courage? Why would that take courage?” Still, I felt bemused when a group of students asked me if I was going to “get in trouble” for working with them to deepen campus conversations on difficult subjects. They understood the culture better than I did.

In 1998, I grew concerned about how the Committee on Faculty’s new leadership appeared to be assessing my contributions. I knew I taught more interactively and less frontally than many of my colleagues, but was surprised to see the committee advise me to do more “teaching per se.” I was likewise nonplussed when they passed on to me a colleague’s suggestion that my academic work was too narrowly focused on women. They did not, as I would have hoped, indicate that in fact I had published well beyond that subject or note that, in any case, no one had ever suggested a “narrowness” to work focused only on men. When I wrote a long letter to share what I found unsettling in their coded language of privilege and discrimination, they questioned why I refused to acknowledge their support and continued to present myself as an outsider. One professor let me know that as he read my letter eight times, he asked himself why I was being such a “baby.” Also, that I was a good writer. Also, that there was something irritating about my smile.

Despite these difficulties, the committee never advised me to delay my tenure process (as they did with other faculty members for whom they had concerns). My book was about to be published by Harvard University Press, and I was deeply engaged with students and community. I persisted in believing that input from the rest of the faculty would protect me. Moreover, no man had been denied tenure on the Cincinnati campus in almost fifty years.

In January 2000, I was invited to the home of an older faculty member whom I really didn’t know very well. He was so disturbed by the unprecedented proceedings at a recent meeting of the full professors to discuss my reappointment, he felt he needed to alert me. He likened the oral report he heard to a grand jury presentation where only the prosecution is allowed to present its case. He described a forty-five-minute “minority report” (accompanying a 3-1 committee vote in my favor) that offered an unrelenting litany of my failings.

That negative report then made its way to the College-Institute provost and president, both of whom were rabbinical school classmates of the committee chair. When the report reached the school’s Board of Governors, member Sally Priesand questioned how this extreme portrayal could conflict so profoundly with her experience of hearing me speak and seeing me interact with students. Her questions were dismissed, and the board was assured that the whole process had been “impeccable.” When the administration announced my nonreappointment to the community at the end of the term, I joined my female colleague in New York as the only people denied reappointment or tenure in recent decades across HUC’s three American campuses. There was no system for appeal.

Offering no meaningful oversight, HUC allowed a few men to conduct a closed process that succeeded in disposing of someone, with the wrong kind of smile, who did not fit their idea of what their first woman faculty member should be. Unlike many in my situation, I was fortunate to have good health; strong support from family, community, friends, and a caring partner; as well as financial resources. Moreover, I was not forced to abandon my academic expertise. Moving back home to Boston to serve as historian in residence at the Jewish Women’s Archive, I was able to begin reassembling the pieces of my personal and professional identities. It is nineteen years later; I know things have changed. For one thing, after my departure, review procedures were introduced into HUC’s tenure process. While there are still only two women with academic appointments in Cincinnati, there are many women throughout the system, including some with significant administrative positions. Still, as the news illustrates every day, we are not yet a society that trusts women and their truths. Most institutions still have work to do, and I believe the best way to support a school that I still care about is to hold it accountable for both its past and its present.

As this #MeToo moment continues to reveal the cracks in our “postfeminist” social order, we need to scrutinize our narratives of gender progress. We may see institutions evolving and women increasingly moving into positions of authority and leadership. We should not, however, assume all those journeys have been smooth. Nor should we trust that the gatekeepers of institutions long dominated by men will know how to relinquish some share of their power and control, even when it has come time for them to do so.

i Karla Goldman, “Women in Reform Judaism: Between Rhetoric and Reality,” in Women Remaking American Judaism, ed. Riv-Ellen Prell (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2007), 109–33.