Academic fields such as History, Psychology, and Transitional Justice have largely ignored this group of individuals, even though they have been speaking and writing about their experiences as well as organizing themselves for decades. For instance, in the 1990s the International Association of Lesbian and Gay Children of Holocaust Survivors was created in New York. At its peak, the association had over 150 members from eleven different countries. There was clearly a need among LGBTQ children of survivors to find each other to discuss and work through issues that they specifically were facing, such as experiences of homophobia from within their families and/or communities. While the organization has since disbanded, their website remains active and provides a snapshot of some of the colliding histories of LGBTQ persecution by the Nazis, the Holocaust, the rise of the modern LGBTQ rights movement in the United States, and the experiences of children of survivors.

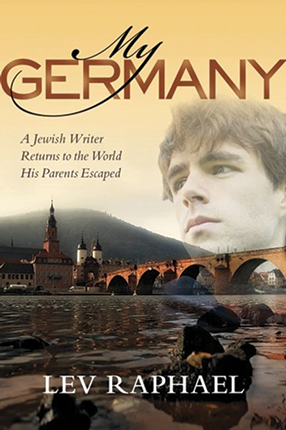

Along with groups such as the International Association of Lesbian and Gay Children of Holocaust Survivors, there exists a small collection of writings from LGBTQ children of Holocaust survivors. The genres of writing include theatre, fictional short stories, autobiographical short stories and memoirs, poetry, and some academic texts. The small collection of authors includes Lev Raphael, Lisa Kron, Rick Landman, and Susan Knabe.

When Raphael’s brother announced his engagement to a first-generation Polish Catholic immigrant woman, Raphael’s family had a difficult time accepting his choice of partner. For Raphael, the engagement also made him question his own emerging Jewish identity. “I wished my brother hadn’t taken something away from the family by marrying a non-Jew,” Raphael writes, “But the experience was odd for me. I was too uncertain in my own Jewish identity to condemn what my brother was doing—or to feel comfortable with it” (13–14). Raphael had been struggling to reconcile his Jewish faith and identity with his growing awareness of his own homosexuality. Struggling with finding his Jewish identity along heteronormative definitions, Raphael felt that his brother had undermined the same normative definers by marrying someone outside the Jewish faith. Alongside this feeling was the realization that even if his brother married a non-Jewish woman, his brother would still always be considered “normal” compared to Raphael because his brother had entered into a heterosexual relationship. “I also felt bested by him,” Raphael writes, “out-maneuvered in our unspoken rivalry. I couldn’t count on marrying even a Jewish woman, and so even though my brother had dropped out of college, he was normal, and had just proven it in the most obvious way” (13–14). His brother’s engagement and subsequent wedding forced Raphael to face the realization that he would never be considered “normal” within his family. His homosexuality dislodged him from the path expected of him and Raphael viewed this as a betrayal to his family, their history, and the Jewish community.

The engagement of his brother and Raphael’s feelings of this event highlight only a small aspect of how LGBTQ children of Holocaust survivors have different experiences from their straight counterparts. In many ways, the experiences of LGBTQ children of Holocaust survivors are unique and demand further study and acknowledgement. LGBTQ children of survivors have also contributed to the rebuilding of the worldwide Jewish community and have worked tirelessly to preserve their families’ histories and memories. These efforts need to be acknowledged and highlighted in academic studies of Holocaust survivors, and also within the larger Jewish and LGBTQ communities.