But why look at the materiality of books? Why study the physical forms that Jewish books have taken? Recent scholarship has alerted us to the obvious but profound insight that we do not read “texts.” A text is a constellation of verbal meaning, an abstraction that exists only in a reader’s head. What we actually read are texts that have been inscribed upon some type of writing platform—a clay or wax tablet, a scroll, a codex (what we normally call a book), or that other kind of tablet made by Microsoft and Apple—in a particular fashion. These concrete specificities of a book’s shape—I’m using the term “book” to include all these different types of writing platforms—profoundly affect and shape the way we read a text—whether the text is hand written or printed; illustrated with pictures or decorated with designs; or accompanied by commentaries on the page; or presented in its naked solitary splendor, to speak only of the most general cases. Each of these modalities of a text’s material transmission has an impact on how we understand its meaning. By “understand,” I mean not just interpret its words, but also comprehend the place that the text as a whole inhabits in the world—its larger cultural, social, literary, and religious significance. And these larger contexts, in turn, profoundly shape the ways in which we read and understand even the smallest textual details. Furthermore, the book as a material object often comes to possess a symbolic or strategic meaning in its own right—religious, political, social—that goes far beyond the meaning of the text it conveys.

In a recent book, The Jewish Bible: A Material History, I explore the various consequences of these insights in respect to the Hebrew Bible (and its various translations) and the changes it has undergone in its material shape from the time of its origins in the ancient Near East down to the contemporary age of the digital book. Within the narrow space of this miniessay I can’t elaborate in detail on any of these changes; but let me offer a few quick examples to demonstrate how different these material forms of the same text—the Hebrew Bible—have been, and the kinds of impact and effects the changes have made.

We can begin with the earliest form of the Hebrew Bible—a scroll made from animal skins. These early scrolls were not, however, the monumental sefer Torah we know today. They were much smaller scrolls, with each scroll typically containing one biblical book—for example, the Torah, the Pentateuch, consisted of five separate scrolls that may have been kept together in a single container—and scribes appear to have written these scrolls not much differently than scribes throughout the ancient Near East and Mediterranean basin wrote other texts. Because of their relatively small size, these scrolls were not difficult to read; a student could easily hold one in his or her lap. In short, they were “ordinary” books.

When the rabbis turned these five scrolls into a sefer Torah, they did more than change the size of the scroll; they radically altered its very identity and character. The sefer Torah is not an ordinary scroll. It is not easily used for reading or study. It is really only fit to be chanted aloud sequentially within the liturgical service in the synagogue. In turn, the rabbis selected from the panoply of scribal conventions with which earlier scrolls had been written, reified them in the form of Halakhah—indeed, they characterized their authority as halakhah le-Moshe mi-Sinai, that is, as laws given orally to Moses on Sinai—and thus brought what they called the Written Torah, the Hebrew Bible, under the mantle of the Oral Torah, namely, the corpus of their own traditions. Through such halakhic stipulations, the rabbis transformed the sefer Torah from a book into a ritual artifact. Over time, the artifactuality of the sefer Torah was itself developed further. By creating dedicated spaces for the sefer Torah within the synagogue’s architecture, by casing and costuming the monumental scroll in differently shaped containers and dresses, and by creating rituals for reading the sefer Torah and for taking it out and returning it to the ark in processions through the synagogue, the rabbis turned the sefer Torah into a kind of icon of the divine presence in the synagogue. (Even if it’s a slippery iconicity: nobody in a synagogue has ever believed they are actually hearing God speak when a ba‘al kore chants from a sefer Torah, or thinks they see God when the Torah is carried around; what they hear and see is the word of God and its writing platform in the form of the scroll.)

In the eighth or ninth century, when Jews finally adapted the codex book form, the Hebrew Bible underwent another major change in its materiality. The codex was not merely a new writing platform. Because it was not subject to the same halakhic strictures as a sefer Torah, the Bible codex represented a new kind of literary space within Jewish tradition. Vocalization and cantillation marks could be written on its pages, as well as additional texts that could never be inscribed in a sefer Torah, like the masorah, a vast corpus of annotations and enumerations of every unusual feature of the biblical text. Most important, the codex was a more economical writing medium than the scroll (if only because scribes could write on both sides of a leaf in a codex, something rarely done in scrolls). The number of Bible codices (and other texts) multiplied exponentially throughout the Jewish world, indeed wherever Jews lived in all their varied diasporic centers.

With the spread of codex production, one of the most prominent features of Jewish book culture also emerged. Jewish books always reflect the materiality of the books produced by the gentile host culture in which the Jews producing their books live. Put simply, this means that a Hebrew Bible produced in an Islamic land in the tenth century will look like an Islamic book of that period, a Qur’an in particular; while a Bible produced in, say, Germany in the thirteenth century will look like a Gothic Latin Vulgate; and so on. At the same time, this very tendency of Jewish books to mirror the books of their host cultures also required Jewish scribes to differentiate their books so as to mark their Jewishness. In the case of the Bible— perhaps the most contested book in all Western culture, with Jews and Christians (and, to a lesser extent, Muslims) fighting fiercely over its “ownership”—the need for Jews to “Judaize” their Bible’s materiality (and distinguish it from its Christian counterpart) is one of the keys to understanding the symbolic, extratextual meaning that these books carried.

A few brief examples will illustrate what I mean.

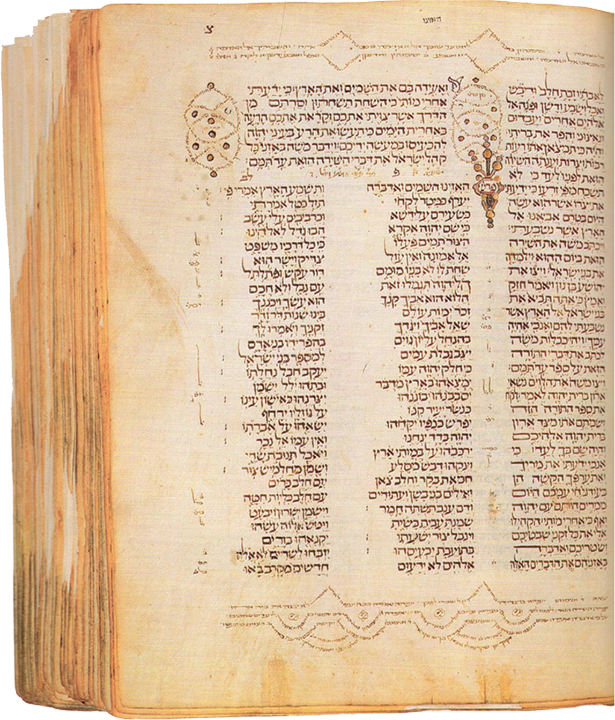

Figure 1 is a page from a Spanish Bible (Jerusalem, National Library of Israel 4o 5147 fol. 90r), written around the year 1300. The biblical text itself—Deuteronomy 25:20–26:17, which includes Moses’s farewell song—is laid out in three columns reminiscent of Torah scroll columns (though here they have both vocalization and cantillation marks), while on the top and bottom of the page the masorah magna is written in micrography, miniature writing, which is inscribed in geometric band-like designs. The two designs of interlocking circles beneath them are also composed of micrographic masorah. As in other Bibles composed in lands which once had been part of the Islamic realm, the designs in Sephardic books tend to be either geometric or architectural or floral, and reflect the Islamic aversion to representational figures. Nor is this the only Islamicizing feature of the page. Between the two columns on the right side and beneath the interlocking-circle design is a parashah (lection) marker painted in gold leaf that resembles an ansa, the ornamental chapter markers used in Qur’ans.

Yet even though this Bible was produced in Spain long after the Christians had conquered it, its material form still reflects that of the Islamic book. This fact would seem to contradict the general rule outlined above that Jewish books tend to reflect the books of their host culture, which in this case was Christian Spain. But this Bible looks nothing like a Christian Bible of the period. In fact, as I and other scholars have suggested, the Islamicizing features of the page may indicate an intentional effort on the part of its Jewish scribe and patron to identify themselves with the other minority culture in Christian Spain—the Muslims—in order to resist the hegemony of the dominant Christian culture. Not looking like the host culture’s books may have been exactly the point of this Bible’s material features.

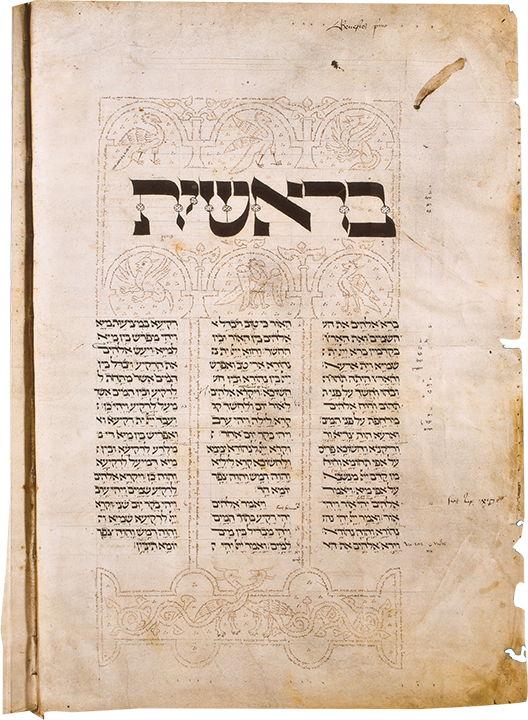

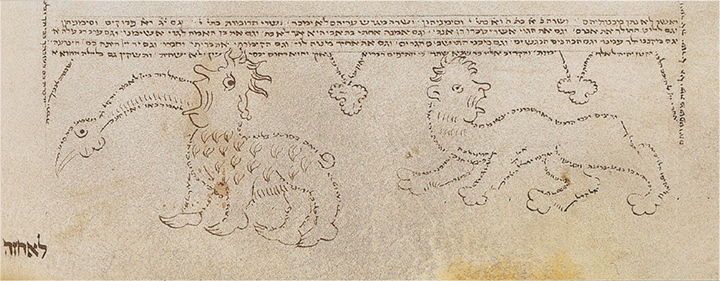

In contrast, figure 2 (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ms or. Fol. 1212 [Erfurt 2], fol. 1v), taken from a giant Bible written in Germany in the late thirteenth century, pictures the beginning of Genesis, which is written in giant Gothic-like Ashkenazic square letters, inside a panel populated with various grotesques—dragons, griffins, and camel-like hybrids—all “drawn” in masoretic micrography. Still more mythical beasts inhabit the roundels at the bottom of the page, again in masoretic micrography. My personal favorite of all these images is figure 3, taken from the same Bible (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ms or. Fol. 1212 [Erfurt 2], fol. 146v), which shows two rather bewildered hybrids, one of them either spewing or swallowing a long-tailed bird of masorah, the other looking dazed over his shoulder. Both look like aliens who have just landed on a Hebrew Bible page from outer space.

These grotesques mirror the marginal drawings found in many contemporary Latin Gothic books, but here they have been “Judaized” by, once again, being composed out of masorah. As such they appear to represent what Ivan Marcus has called “inward acculturation,” the process by which Jews absorbed and Judaized practices and beliefs from the surrounding Christian culture and thereby made them their own. In the case of both the Sephardic and Ashkenazic Bibles, the masorah written on the page may have been difficult or even impossible to read, but it was not on the page to be read but to serve the purpose of “Judaizing” the book. In the two cultures, the strategies of Judaizing—in one case, identifying with the book culture of the Muslim minority in order to reject that of the Christian majority; in the other, appropriating the imagery of the majority book culture but Judaizing it—may have differed, but it is significant that both used the masorah, the traditional mark of the Jewish Bible, to accomplish their strategies.

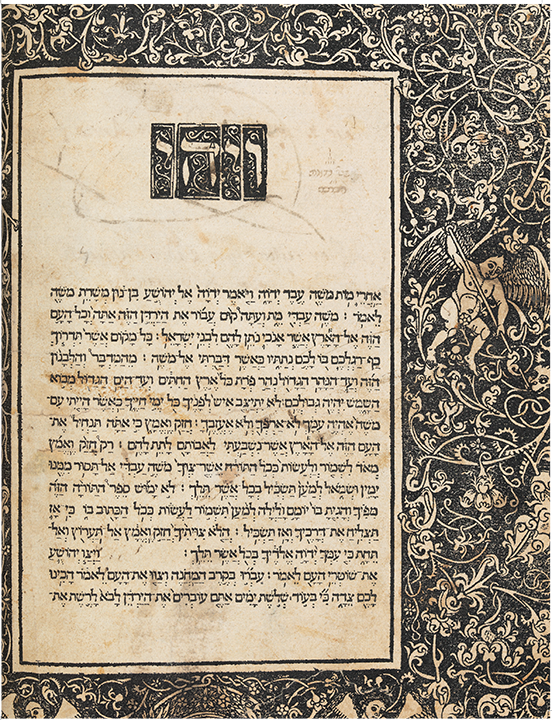

A final example, from an early printed Bible, the editio princeps of the entire Bible published by Joshua Solomon Soncino in Soncino, Italy, in 1488, will illustrate still another conception of the Bible. Figure 4 (Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Holkham c.1, fol. [107r]), pictures the elaborate opening page of the book of Joshua. The text is set out in a single wide column surrounded not by the traditional masorah, but by an elaborate wood-cut frame that depicts, against an elaborate floral background, a flock of putti, little naked cupid-like creatures cavorting in the margins with spears and bows and arrows in their little hands. This frame is a masterpiece of early book art; as we know, Soncino bought it from another Italian printer, Francesco del Tuppo, who had commissioned it for a deluxe edition of Aesop’s Fables (Naples, 1485). Soncino doubtless reasoned, somewhat talmudically, that if Aesop deserved a frame of this ornate beauty, then all the more so did a Jewish Bible. Despite its apparent incongruity, the frame breathes all the ornate worldliness of Renaissance Italian culture onto the pages of the book, casting the Bible virtually as a work of art within its frame.

The texts in these separate Bibles are more or less identical, but by studying the changing material shapes of these books, one can discern the different meanings that the Bible—as an object, not just as a text—assumed in Jewish culture in its various centers and historical periods, and the separate roles that the Bible, as an iconic object of Jewish identity, occupied in the Jewish mentality.

The observations I’ve made in this short essay are all drawn from the field now known as the history of the book. This is not a truly new area of scholarship, but it has gained a new prominence and profile within the past several decades, no doubt because we have now entered a new period in book technology, the digital age. The awareness and anxiety attending this recognition has led scholars to turn to the past in order to study earlier transitions in the technologies of reading and writing, doubtless with the hope that understanding the past will help navigate the present, if not the future. What will happen to the Jewish Bible in the digital age? I’ve gotten some flak for an assertion, in the epilogue to my book, that the digital age will not radically transform the Jewish Bible, not at least as much as it will change (and already has) other Jewish texts like the Talmud, the prayer book, and the Passover Haggadah. I’m willing to defend my assertion, but the truth is that, if there will be a radical change, it is unimaginable now. Still, if the only thing the digital age accomplishes is leading us to look back at the rich and neglected history of the material Jewish book, dayyenu.