Contemporary Jewish art unifies two disparate things, Jewish subject matter and avant-garde artistic process. The artistic processes used by these artists originated in the 1960s. At that time minimal art, conceptual art, and postmodern dance expanded what materials and techniques artists could use. Over the intervening years, artistic process and materials have expanded further. Artists can use nearly whichever material they choose. Similarly, in the past, Jewish art included a specific array of subject matter that tended to be limited to biblical stories and characters, the Holocaust, or personal experience. (Think of Marc Chagall’s whimsical recollections of childhood scenes, or George Segal’s sculptural figures that make up his Holocaust group.) As the twentieth century progressed, abstraction and the spiritual character of painting were added to the mix. Even as Jewish subject matter expanded, the question of style or the definition of Jewish art continued to be asked. Harold Rosenberg asked it in an article titled “Is there a Jewish Art?” in 1966. Jewish artists still use these subjects but some look elsewhere for Jewish references and they use a source that is at the heart of Judaism but rarely opened to artistic inquiry, until now—Talmud.

The impulse to turn to Talmud seems quite natural to me. Let me explain. I received my MFA from Pratt Institute. At that time, I studied the conceptual artists and postmodern dancers from the 1960s. They challenged and expanded what materials and processes artists could apply. Some artists, reacting against the individualistic expressionism from the previous decade, tried to remove the personality from their work. To do this, some artists, such as Sol Lewitt, set up strict rules for themselves. For example, a drawing might be made with only straight parallel lines. To make the drawing, the artist simply had to execute the action.

I found art made by rules very interesting but at the same time thought that as artists developed their own working methods, those methods remained just as individualistic as the abstract expressionists. A boxy sculpture might seem cold and emotionless whereas a splatter painting might be full of energy and force. Nevertheless, both works followed an artist’s spoken or tacit consideration, “How am I going to make an artwork?” For me, pulling my own artistic rules out of thin air, be they expressive or analytic, isn’t enough. Instead, I wanted to find guidance from a source outside of art making. It took me several years to find it.

While in graduate school, I spent a summer in Venice, Italy. I was enthralled by the city. Who isn’t? Of course, the canals and boats, sunlight and colors, were all captivating, but so were the streets, some only as wide as a linebacker’s shoulder pads. To find my way through the maze, I would follow local Venetians. I came to understand how they traveled over bridges, along alleyways, and into passages that ducked under buildings. Theirs was a three-dimensional map.

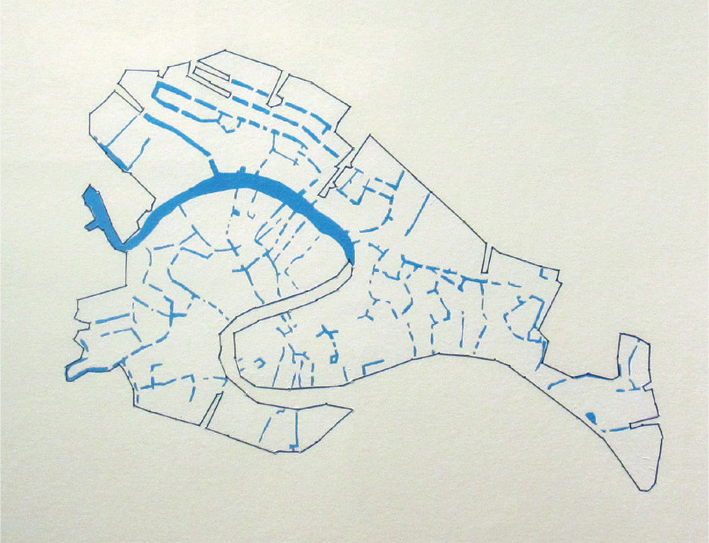

Years later I stumbled upon a map of the Venice eruv. An eruv is a legal notion that blends individual properties into one collective home. This allows Orthodox and traditional Jews who keep the Sabbath (shomer shabbat) to carry some things from place to place within the boundary, an activity ordinarily prohibited. When I saw the Venice eruv map, I was suddenly transported back to the city but with a new understanding. The pathways I travelled were not only routes connecting the Piazza San Marco to the Accademia Bridge, but they might also be boundaries that define inside and out. In America, many eruv boundaries have sections made out of wire. Often, some of that wire is already in the urban landscape. Electrical and telephone utility wires can be integrated into the eruv perimeter, or at least an additional wire is often hidden among them and maintained by the utility company. Utility wires’ original purpose is to transport information or energy from one place to another. In this way, a utility wire and a street are alike—they both have direction. The eruv adds another layer of meaning to each of these paths; they become part of a perimeter, a silhouette, the boundary of a neighborhood. I very much like the idea that a line can have direction and define the edge of a shape simultaneously.

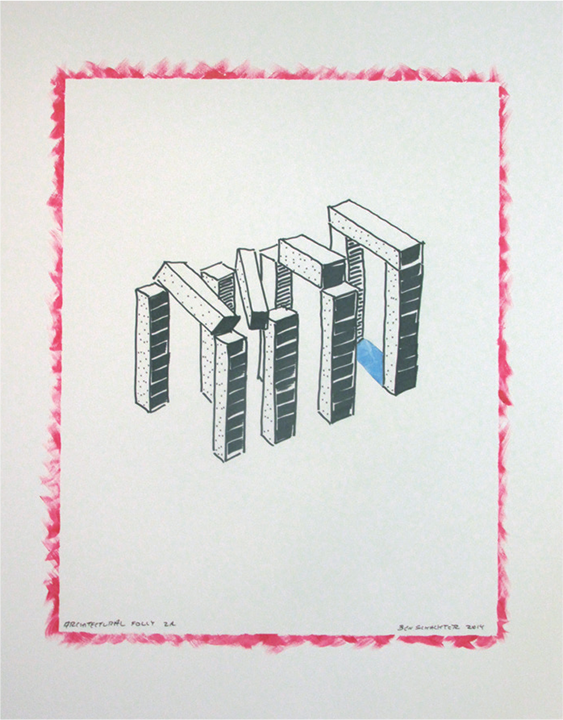

My eruv paintings are based on eruv maps and are made out of acrylic and thread on paper. I embroider an eruv perimeter with blue thread through the paper. The interior of the shape I paint white so that the delicate line holds the viewer’s attention. Some maps are more complicated than others and as I consider each one, I wonder about the rabbi/ architect who is responsible for making each decision along the route. Venice Eruv 2007 was my first painting. It was followed up by others, including: Teaneck Eruv, Johannesburg Eruvin, and more.

I am one of a small but growing number of artists interested in referring to talmudic ideas and rabbinic discussions. Some of us accept the tradition to read a page of text every day, a tradition called daf yomi. British Artist Jacqueline Nicholls studied Talmud earlier in her education but now wonders what else is in the corpus. As a way to understand the text, as well as to draw out her own interpretations, Nicholls is in the middle of an enormous series of drawings called “Draw Yomi.” Yes, a new drawing every day relates to the page she reads. Israeli Andi Arnovitz also refers to talmudic texts in her work and makes biting commentary regarding how rabbinic authority in Israel treats women in divorce and reproductive traditions. And back here in the United States, painter Archie Rand’s monumental series of all 613 commandments, as itemized by Maimonides, was on view at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. I also use Talmud as a source for subject matter, but my interest in the text tends toward descriptions of how things are made. Each artist uses talmudic texts and rabbinic discussions differently. Those differences might be idiosyncratic, yet the choice to look at the Talmud is shared among the artists. The Talmud is an ancient text, but as more artists explore how it can be used as subject matter for contemporary art, we put that old text into new bottles, or better, new media.