“Jews have an interesting position in South Africa,” the artist William Kentridge once told a New York journalist from The Jewish Week. Jews have indeed led an awkward, ambiguous existence in South Africa over the last century, as scholars such as Claudia Braude and Shirli Gilbert have demonstrated. They have been haunted by the European violence they were lucky to escape and fearful of Afrikaner anti-Semitism. Yet, while a significant minority of South African Jews opposed the apartheid regime after 1948, a majority accommodated themselves to their country’s racist social architecture. Kentridge, a Johannesburg-based visual artist and a leading figure in the global art world during the last decade—does not depict that “interesting position” in a direct way. Very few—if any—overtly Jewish motifs manifest themselves in his work; furthermore, the content almost never pertains to Jewish history, culture, or religion. Nevertheless, I argue, Kentridge has developed an aesthetic project that speaks both to a generalized diasporic condition common to Jews (and others) and to the intensely local position of South African Jews at the interstices of an infamously racialized society.

Kentridge’s approach to Jewishness is similar to—and, in fact, overlaps with—his approach to social and political questions in general. Coming from a Lithuanian-and German-Jewish Johannesburg family prominently involved in the anti-apartheid struggle, Kentridge makes art that is weighted with political implication while critiquing politics, for the most part, indirectly. Although Kentridge’s work spans multiple media, including drawing, sculpture, theater, and, most recently, opera, I focus primarily on one work from the open-ended series of short animated films that he calls Drawings for Projection. Kentridge began that series in 1989, a year in which apartheid entered its final death throes in the face of massive political mobilization. The series registers this history obliquely, primarily by employing the lens of a private life that opens onto adjacent social questions. In fragmentary form, the films tell the tale of the industrialist Soho Eckstein and the artistic Felix Teitlebaum, two men who physically resemble the artist and serve as his alter egos in a simultaneously comical and serious reflection on contemporary South Africa. The films, which include occasional intertitles and bits of text but no dialogue, recount a love triangle between the two men and Mrs. Eckstein. They also track the rise and fall of Soho’s business empire while alluding to South Africa’s history of racialized violence and the political struggles marking its transition from apartheid to representative democracy. A significant dimension of Soho’s empire includes a mining concern established in an area recognizable as the East Rand, the gold mining region adjacent to Johannesburg. This mining landscape is one site where Kentridge develops an understanding of South African Jews as “implicated subjects,” who are ethically and politically intertwined with the contemporary and historical injustices that mark both South Africa and more global histories of racism, slavery, and genocide.

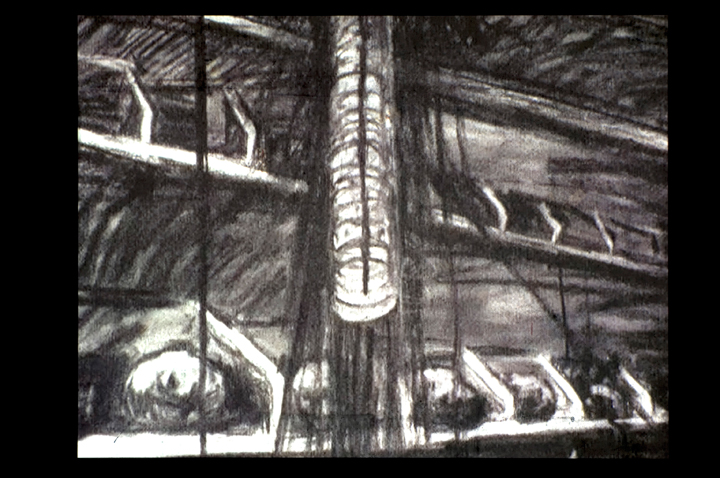

The themes of the Drawings for Projection powerfully suggest these local and global histories, but Kentridge’s unusual technique provides our best access to the questions they raise. Unlike traditional animation, in which the filming of a large series of images creates the illusion of movement, Kentridge works with a small number of drawings (typically between twenty and forty for an eight-minute-long film). His process of “drawing for projection” is based on marking, smudging, and erasure. He draws an initial image on a white sheet with charcoal—occasionally supplemented with blue and red chalk—and then walks across his studio to his film camera, where he shoots two frames of the image. He then returns to the drawing and amends it through additional drawing, smudging, and erasure, before shooting two more frames. The process of creation continues likes this for a period of months and results in a film that preserves layers of residual charcoal dust and concatenates palimpsestic images where traces of previous drawings remain on celluloid and in the final film even as the drawings themselves that make up each frame disappear forever (except for the final image in each sequence, which is sometimes displayed in exhibitions alongside the films). Time is made concrete by a technique that simultaneously ensures disappearance and preservation. In this manner Kentridge turns animation into a medium for reflecting on memory and forgetting. When Kentridge uses this technique to explore South Africa’s mining landscape, a traumatic Jewish history also emerges, but it emerges in contact with other histories of violence.

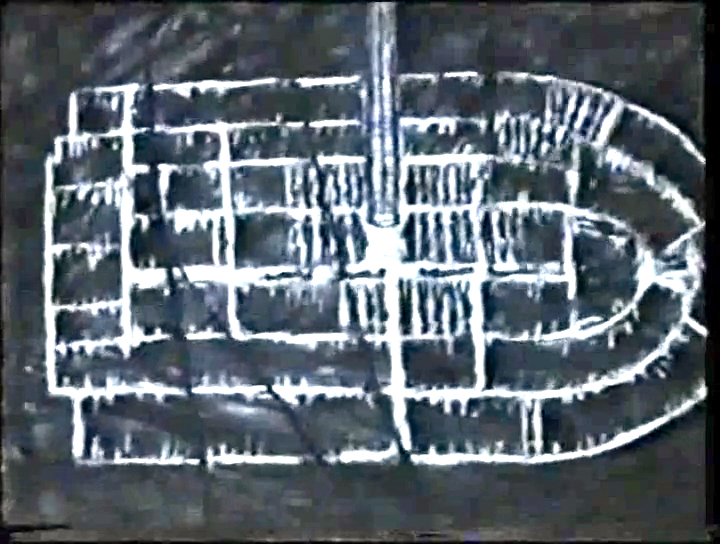

Mine (1991) was created as the third of the Drawings for Projection, following Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (1989) and Monument (1990). Johannesburg documents the creation of Soho’s empire, including the mining town we associate with the later film, while Monument shows Soho as supposed “civic benefactor,” hypocritically erecting a statue in honor of the workers. Mine, in contrast, reveals the underside of Soho’s empire in no uncertain terms. This revelation takes place most dramatically in a sequence that begins with Soho’s coffee pot—a cafétière, as Kentridge calls it, or what we call in the United States, a French press. While enjoying breakfast in bed, Soho presses down on the plunger of his coffee. However, it does not stop at the bottom of the pot, but continues its downward movement through the floor and into the mines below. The coffee plunger creates a miniature mineshaft that cuts into the living and workspaces of the miners, passing through their barracks and showers and into the cavernous mines themselves. As the scene proceeds, Kentridge reveals that his drawing technique partakes of the violence it depicts, an implicit commentary on the complicity of the artist in a world of structural oppression: the plunger becomes a kind of drill and is associated both with the drilling performed by the miners and with the artist’s own pencil. As the drill cuts into the rock, an image emerges that is soon recognizable as the cross section of a slave ship. A second association joins this reference to slavery: the iconography of the mine also resembles a Nazi camp. Indeed, the image of the compound seems to be modeled on a famous photograph from the liberation of Dachau (one which apparently features a young Elie Wiesel), although Kentridge claims not to have had the Holocaust in mind at all. Regardless of the artist’s intentions, however, recognition of this modeling also casts a dark shadow over the images of miners in the shower, which can now be seen as an oblique reference to the gas chambers.

The film contains no clear narrative line or voiceover to guide interpretation of what I would call the film’s “multidirectional” visual associations. If these are memories that are excavated from the formations of the mine, it is not clear whose memories they are. Out of this uncertainty emerge two ways to read this sequence, which correspond, in turn, to the two ways that the historical references arise in it: the unmistakable allusion to the slave ship is emblematic of a collective memory (and forgetting) of the larger historical transfers and correspondences between different forms of violence connecting Europe and Africa (and theorized by the likes of Aimé Césaire and Hannah Arendt, among others); meanwhile, the unconscious and ghostly presence of the Nazi camp suggests the peculiar psychology of domination and complicity of white and—perhaps more pointedly—white Jewish South Africans.

If we interpret Soho’s name, Eckstein, as an indirect indication that he is of Jewish descent—a new message emerges. Given the associations created by Mine, Soho’s iconic pinstriped suit becomes a displaced reminder of the concentration camp uniforms that Soho never had to wear. The shadow of the Holocaust references the partial similarity between German and South Africa racist regimes as well as the presence of virulent anti-Semitism that accompanied Afrikaner nationalism, especially during the Nazi period in Europe. It might also draw attention to the vast distance of South African Jews from the Holocaust: the fact that immigration to South Africa represented asylum for many, if not simply a bit of historical good fortune (the case for Kentridge’s own family). The irony that, despite its racism and anti-Semitism, South Africa was a refuge for Jews during World War II is noted by the South African-British writer Dan Jacobson, who writes of his grandmother and her children: “In leaving Lithuania for South Africa, they had exchanged an anonymous death at the hands of murderers for life itself.”

If South African Jews were distant from the Holocaust—and yet still implicated in it by virtue of the loss of families and ancestral communities destroyed in the genocide—those same Jews were now uneasily integrated into a new, also violent context. Kentridge captures this new form of implication in the doubled figures of Felix and Soho. On the one hand, Felix seems more aware of the racist violence around him, although he remains separate from the political struggles that surround him. In the figure of Soho, on the other hand, we are reminded of the Jewish financiers who, in the late nineteenth century, fostered the growth of the mining industry. In the words of critic Claudia Braude, “The history of the Johannesburg Jewish community . . . is intimately intertwined with the history of the early mining town.” Soho’s mine becomes a historical allegory for one strand of Jewish South African history, but in the artist’s hands this allegory is many-sided.

Kentridge’s palimpsestic art—along with the multidirectional legacies it evokes—registers several things simultaneously. It uncovers the specific dynamics of South Africa’s political interregnum but also demonstrates how the larger forces of capitalism, colonialism, and genocide have framed South African history over the longue durée. It draws attention to the specific, ambivalent position of the country’s Jewish minority, yet also anticipates a more general return of suppressed memories that would accompany the end of apartheid. What the movement of the coffee plunger in Mine reveals is not simply a historical analogy between different sites of violence or Soho’s (or Kentridge’s) individual unconscious. It also evokes a complex history of trauma, implication, complicity, and forgetting that defines a social group—South African Jews—caught in that “interesting position” between accommodation and marginalization.