“Shaping Community: Poetics and Politics of the Eruv,” ISM Gallery of Sacred Arts, Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life at Yale, Yale School of Art, October 2012–January 2013, curated by Margaret Olin.

“It’s a Thin Line: The Eruv and the Jewish Community in New York and Beyond,” Yeshiva University Museum, October 2012–June 2013, curated by Zachary Paul Levine.

These two exhibitions focus on the eruv, a barely visible enclosure that according to Halakhah transforms an outdoor space into a shared courtyard and enables Jews to carry objects on the Sabbath. The exhibitions at the Yeshiva University Museum and at the Yale School of Art demonstrate how this aspect of Talmudic law is a living spatial practice. Once defined in the language of anthropology, the eruv becomes interesting for its capacity to chart the radically different ways people experience the same space (and the radically different ways exhibitions treat the same subject).

The Yeshiva University Museum exhibition takes a more straightforward, historic approach. Curated by Zachary Paul Levine with the rabbinic guidance of Rabbi Adam Mintz, the exhibition begins with three early printings of Tractate Eruvin, the Talmud volume concerning the laws of eruv, which include occasional hand-copied schematic drawings to illustrate the opinions of rabbinical commentators. This directional framework—text to practice—defines the curatorial approach of the Yeshiva University Museum exhibition.

The exhibition meticulously reconstructs the passionate rabbinic debates surrounding the eruv and demonstrates how modern Jewish communities applied these opinions in practice. It focuses almost entirely on New York City and its surrounding Jewish communities. At least half of the exhibition explores the history of the Manhattan eruv, the only American community eruv from the end of World War II until the early 1970s. The exhibition presents the bureaucratic hurdles of securing local government approval for construction and rabbinic controversies surrounding proposals for new eruv boundaries. The engagement between religious and secular leadership in the local project reveals a little-known story of postwar Jewish life in New York, a history that is typically told from the perspective of the Jewish commitment to Israel and Russian Jewry. The displays reference local landmarks like the Second Avenue elevated train track and local Jewish celebrities such as Rabbi Yehoshua Seigel, which serves to reconstruct vivid experiences of the city during the period of its largest absorption of Jewish immigrants. This anchoring of Jewish geography to the New York City map celebrates that icon of American life—a close-knit hamlet community—right in the middle of the congestion of modern urban life. R. Justin Stewart’s installation Extruded offers a visual echoing of the various iterations of the Manhattan eruv, as described by the rabbinic responsa on the surrounding walls, by hanging blue and white rayon threads at different levels from the ceiling. While Stewart’s three-dimensional map created by the individual strings is difficult to read in space, the shadow they create on the raised white platform below is immediately recognizable as the iconic map of Manhattan. Stewart’s nearly invisible lines invite critical analysis of how boundaries only exist in relation to the space outside (a category with aesthetic implications); yet, the placement of the installation in the center of a room that otherwise displays the chronicles of controversial rabbinic treatises casts the artistic installation into the context of halakhic commentary.

As reflected in the show, the thin line of the eruv strongly impacts those communities living within its borders. The exhibition even pays attention to the culture that grows around the absence of an eruv, from a display of accessories worn to enable pedestrians to carry home keys (such as key tie-clips, belts, and bracelets) to Yona Verwer’s installation Tightrope, which looks at how the absence of an eruv on Manhattan’s Lower East Side affects the lives of the infirm and Orthodox women with young children. Tightrope’s sixteen panels create an impenetrable enclosure of their own, with images of synagogue interiors that mothers and the disabled can rarely visit on the Sabbath because of the lack of an eruv. While the exhibition considers how Rabbi Moshe Feinstein’s strict opinion against the construction of an eruv in his Lower East Side neighborhood still affects women decades later, the exhibition ignores the culture wars embedded in suburban eruv politics. Outside the Daily Show segment on the proposed Westhampton Beach eruv, no reference is made to the overlapping contexts of the non-Orthodox Jewish and Orthodox Jewish experiences in the suburbs. Friction over eruv construction permits, with its First Amendment overtones, is typically a more prosaic suburban battle over public monies, as Orthodox communities, with their private yeshivas, large families and kosher-only establishments, compete with incumbent non-Orthodox communities over zoning, public school budgets, and local culture.

In contrast to the Yeshiva University exhibition, the triumvirate of exhibitions on the eruv mounted at Yale University does not rely on rabbinical advisors or religious perspectives. Conceived and curated by art historian and artist Margaret Olin, these shows look at the eruv as a minimalist architecture with rich metaphoric implications of place and boundary. When Olin does harken back to Jewish texts that discuss the social practices of eruv, these are excerpted quotes from such varied authorities as Maimonides, Franz Kafka, and Michael Chabon. These texts are framed in simple black wooden frames and hung on a white wall, as befits the display practices of modern art.

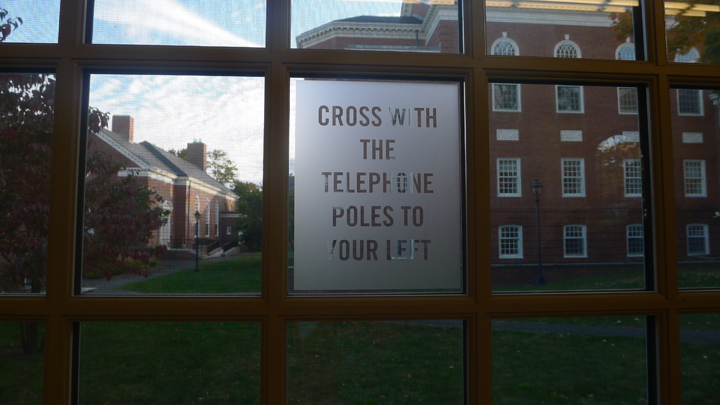

Olin describes the eruv as “urban bricolage” for its creative use of preexisting infrastructure; rather than use Talmudic text as a blueprint for the living spatial practice of the eruv, her curatorial focus is on how the eruv itself, with its metaphoric potential and its appropriation of borders, is a source of inspiration for contemporary art projects. The number of works on display at Yale is only a fraction of the circa two hundred items on display at Yeshiva University Museum, but Olin has mounted the larger exhibition by far. The exhibition turns its visitors into pedestrians within the Yale eruv, activated by the boundaries of the three different exhibition sites as delineated on a map on the inside back cover of the exhibition catalog. The experience evokes that of Orthodox students walking the campus on the Sabbath; however, in this case, displays of modern art, rather than Jewish liturgical spaces, are the destination sites. In Suzanne Silver’s text-sculpture, Kafka in Space (Parsing the Eruv), neither the Talmud nor related rabbinical rulings inform the work; instead, the artist explores Franz Kafka’s fictional treatment of the eruv, and how the leitmotif of the eruv throws the idea of legislating private life into high relief. Some of the artists touching on the subject of the eruv appear in both the Yeshiva and Yale exhibitions, such as Ben Schachter’s embroidered eruv maps and Elliot Malkin’s “Modern Orthodoxy,” which uses a laser to check the eruv. Their appearance at Yale is for the artistic questions that they raise, and their appearance at Yeshiva University is for their visual mediation of ever-evolving halakhic questions.

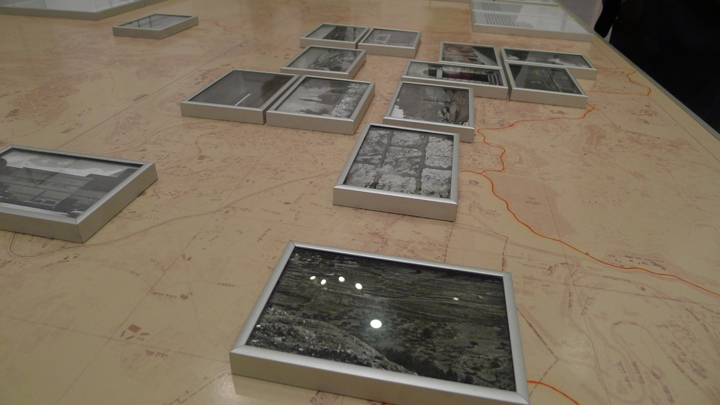

The Yale exhibition includes six photographers (Sophie Calle, Aklan Cohen, Daniel Bauer, Avner Bar-Hama, Margaret Olin, Ellen Rothenberg), four of whom feature disruptive divisions in Israel, one of whom focuses on the nearly invisible eruv that surrounds the Yale campus, and one who draws the Talmudic measurements of the eruv across her own body. Although the extroverted Israeli eruv, the introverted New Haven eruv, and the female flesh eruv make for fascinating social commentary, the insistent appearance of the thin line of the eruv across all the photographs turns the thin line into a formal element, like the clotheslines that cut across buildings in Paul Strand’s photographs of New York in the 1920s. With the broad focus on the nature of boundaries, the third part of the exhibition includes Shirin Neshat’s video, Turbulent (1998), which does not refer to eruv in any form but makes use of the subject of boundaries to evoke divisions between men and women in contemporary Iran.

The eruv provides an elegant tool for mapping modern Orthodoxy as a habitat and as a subject. The viewer of these two exhibitions might wonder how to chart the terra incognita of the Jewish experience outside the eruv or whether new edges could be inscribed through the eruv’s boundaries. How would one map the way Orthodox Jews, unable to afford living within the eruv, organize themselves outside the boundaries of its steep real estate prices? How would one represent Jewish communities that drive to synagogue on the Sabbath and do not subscribe to the concept of eruv?